lumalalim sa kababawan, lumulutang sa kalaliman

Poklong Anading

Silverlens, Manila

About

Mula sa Lubi Art Residency Program ng Davao de Oro tungo sa unang pag-ulit ng kanyang pagtatanghal sa New York, ang paghahalo ni Anading ng mga muling-ginamit na mga materyales dagdag sa makabagong pagpapahayag sa sining ay magkakaroon ng panibagong pagtatanghal para sa mga naninirahan sa Metro Manila sa isang parangya sa Silverlens Gallery. Ang paghahalo sa kanyang mga naging pagtuklas sa pagsisid kasama ang mga nagkusa, mga marinong dalub-agbuhay sa pangunguna ni Maestro Inigo Taojo ng Davao Gulf Divers, mga inisyatiba sa panumbalik ng mga bahura at kapaligiran nito, at sa pamamagitan ng kanyang pagsisiyasat ng materyal upang makabuo ng gawaing sining, ang kanyang bagong pagtatanghal ay naghahatid ng isang uri ng “resurfacing” o panumbalik sa ilang realidad at materyales galing sa kailaliman ng dagat at pagmuok ng kalikasan sa pagkonsumo at mga modang balat-bunga.

Pinapakita sa pagtatanghal ang kanyang konseptwal na pag-atake sa pamamagitan ng paggamit ng iba’t-ibang likas-sining - bidyo, mga iskultura, larawan at mga guhit - lahat nagmula sa kanyang mga ekspedisyon sa pagsisid sa iba’t-ibang lugar-sisiran. Isa sa kanyang pangunahin na nakuha sa karagatan ay ang “ghost net”, na ginagamit sa panghuhuli ng isda, at kalaunan sa pagharang sa mga basura upang hindi anurin tungo sa mga malalapit na baybayin - ay tinubuan na ng pulo-pulutong ng taliptip, koral at algae sa ilalim ng dagat, na maaaring magdulot ng pinsala sa buhay-dagat. Pinihit ni Anading ang paraan ng pagtanggal at pagpanumbalik sa mga iniwan ng mga lambat sa isang bagong anyo bilang di-likas na mga koral, bilang pagpugay sa mga anyo ng buhay na nagambala tungo sa isang malaking paglilok na magpapatingkad sa kabalintunaan ng sitwasyon - na isa ring pagbubunyag sa katangian ng sining: ang paglikha ng mga bagay na gawang-tao na sasalungat sa isang mundo na gawang-tao din.

Ang paghawak sa ideya na ang bawat pagsisid ay isang sisid na paglilinis, at ang pagtuklas sa isang pinabayaan na lambat sa pangingisda, ay naging panimula para sa kanyang pangunahing likha na pinangalanang recruit (No.1), na lumantad bilang isang malaking instalasyon na isang pulutong ng mga likha na nakatali sa dingding sa pangunahing tanghalan (Main Gallery). Ang terminong “recruit” ay nagmula sa Latin na recrescere - re nangangahulugang “muli” at crescere na ibig sabihin ay “sumibol” - ay nagmumungkahi ng pagpapanibago at muling pagkabuhay. Ang likhang ito ay muling nagharaya sa lambat bilang isang retaso ng epekto ng tao at maaring ‘substrate’ para sa pag-usbong ng bagong koral. Sumasalamin ang posibilidad na pagpapatatag laban sa agos ng karagatan, na ang mga lambat ay maaaring tagakatig ng mga koral upang lumaki ng hiyang sa paglipas ng panahon - ang pagsasanga palabas at paghuli sa repraksyon ng sikat ng araw sa mabagal na ugong ng pagbabagong buhay. Mukhang lumilitaw ito sa mga yugto na makikita sa pamamagitan ng kasama na bidyo: ang pagtuklas sa lambat, ang pagkabawi at pagbabagong anyo, at ang paglilipat ng “recruit” balik sa bahura. Magkakasama, itong mga elemento na ito ay bumubuo ng biswal na salaysay sa pagbabago sa ekolohiya, ng pagbibigay diin sa malikhaing kasanayan na maaring lumahok sa pagkukumpuni ng kapaligiran at sa pagbibigay ng bagong perspektibo sa mga hanay ng pagkawasak at paglago.

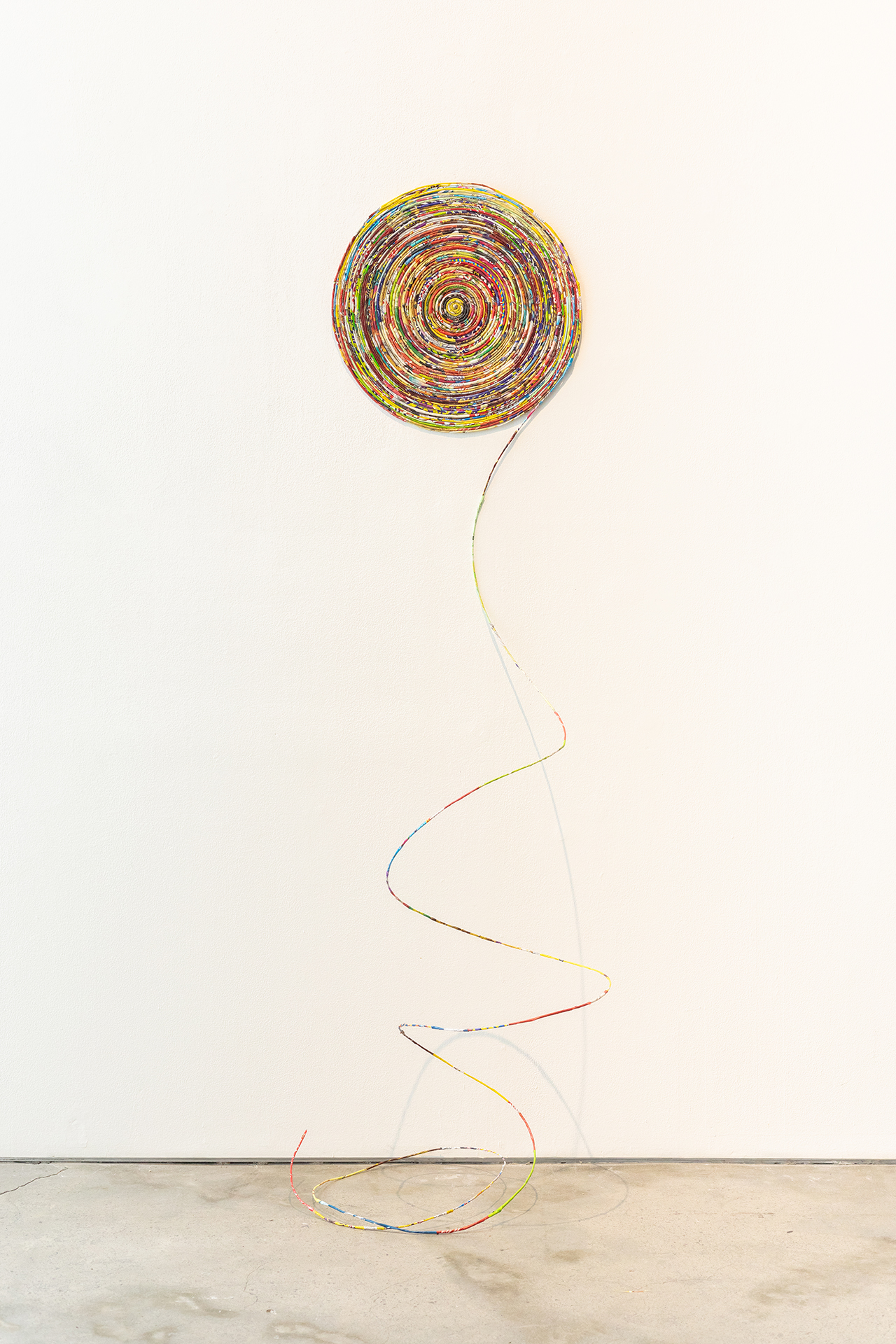

Sasalubong sa atin ang iba pa niyang trabaho pagpasok sa tanghalan kung saan dalawang eskultura gawa sa hindi-kinakalawang na asero na binalot sa mga kaputol na plastik na pakete na tinipon sa iba’t-ibang pagsisid. Isa pa na nakabalot sa kabila ng malaking pader sa kaliwa - isang yaring-kamay na ‘cyclone fence’ - habang ang iba ay lumilitaw na isang rolyo kaharap ng pasukan, umaalingawngaw ang agos ng tubig at kumpas ng pagbenda. Itong mga gawaing sining ang nagbubukas sa pagtatanghal at paggunita sa kanyang mga eksperimento sa pagtalukbong at pagbigkis. Ang tema ng plastik bilang bakas ng tao ay nagpapatuloy sa kabuuan ng mga likha ni Anading, at karaniwan sa kanyang mga nakaraan na pagtanghal at pagsubok. Ang daan patungo sa pagsisiyasat dito ay nagsimula sa lipong pagtatanghal sa CCP na Normal Scheduling Will Resume Shortly (curated ni Dr. Vincent Alessi) at sa trabahong mankay (2019) kung saan ang pagbenda ay umusbong bilang pagpapahayag ng pangangalaga at pagtugon sa pinsala. Ang salitang ‘mankay’ na galing sa Tamil, na ibig sabihin ay “fruit of the mango tree” ay muling naisip bilang “fruit of man” na sumasalamin sa likha ng tao at sa mga materyal na bakas nito. Ang ideya ay nagmula sa mga sanga ng punong mangga sa tabi ng kanyang dating estudyo, kung saan ang mga nalaglag na mga bunga at dahon ang sanhi ng pagtagas ng bubong. Ang mga sanga na pinutol, at kalaunan ay binalot sa pakete ng tinapon na plastik, ay mayroong pag-alingawngaw ng pagkakatulad sa ikot kung paano ang kalikasan at sangkatauhan ay parehas na lumilikha at siya ring lumalamon sa sarili nilang mga prutas. At nuong ang puno ay tuluyang pinutol, ito ay iisang naging pag-alay at pag-dalamhati. Ang tema ng plastik bilang bakas ng tao ay nagpapatuloy sa pagtatanghal sa pamamagitan ng paggamit ng “ghost nets.”

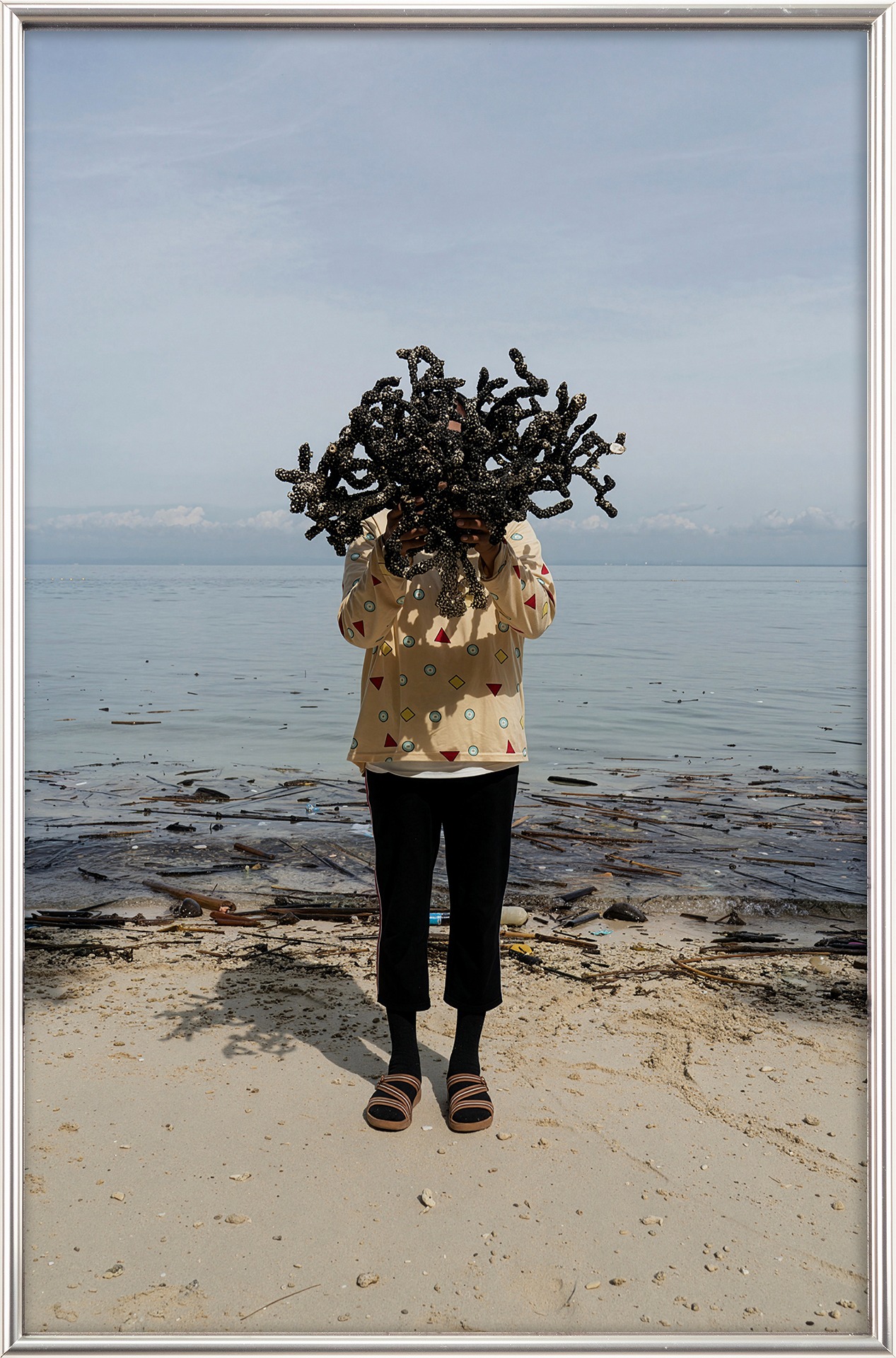

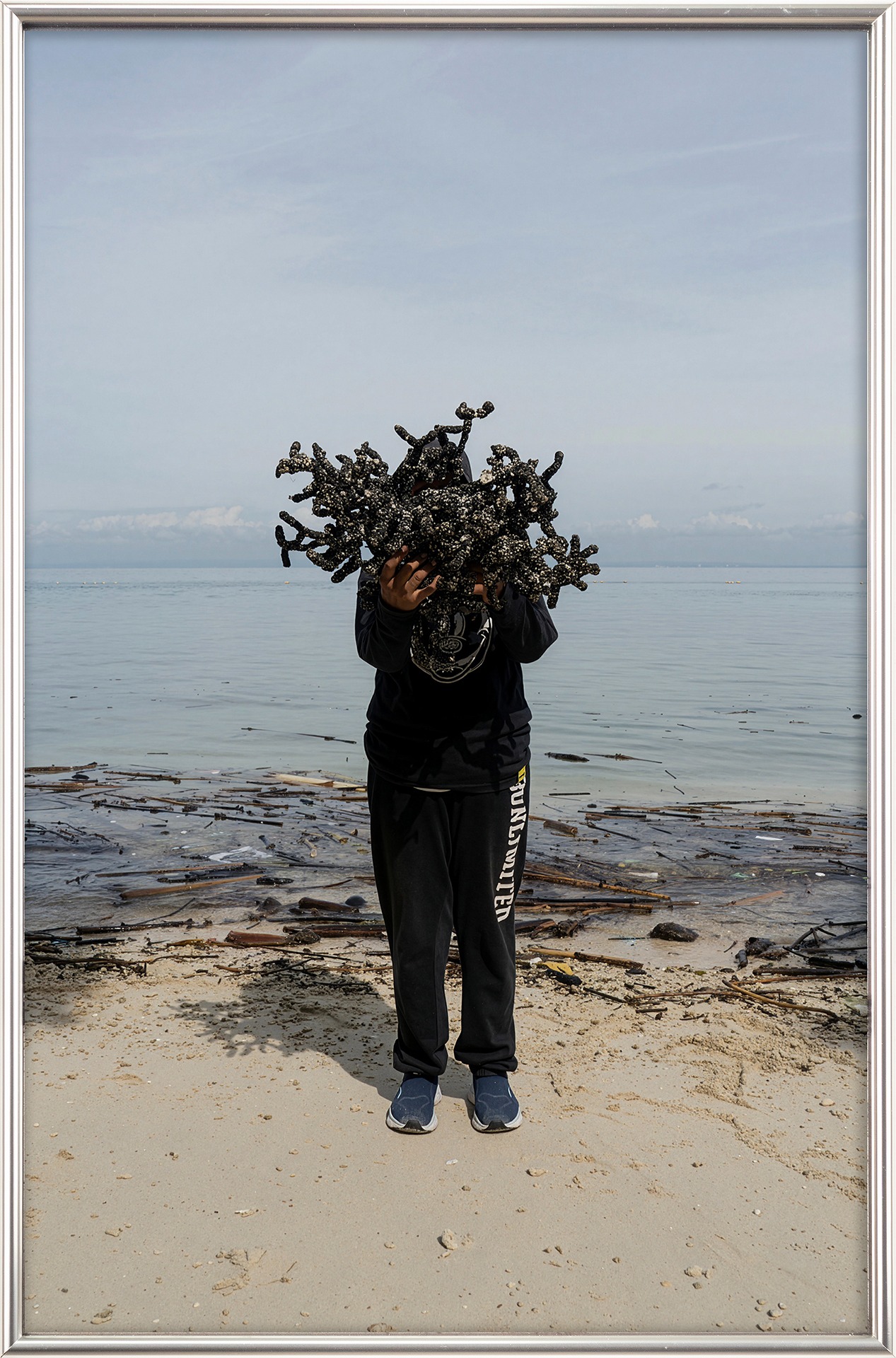

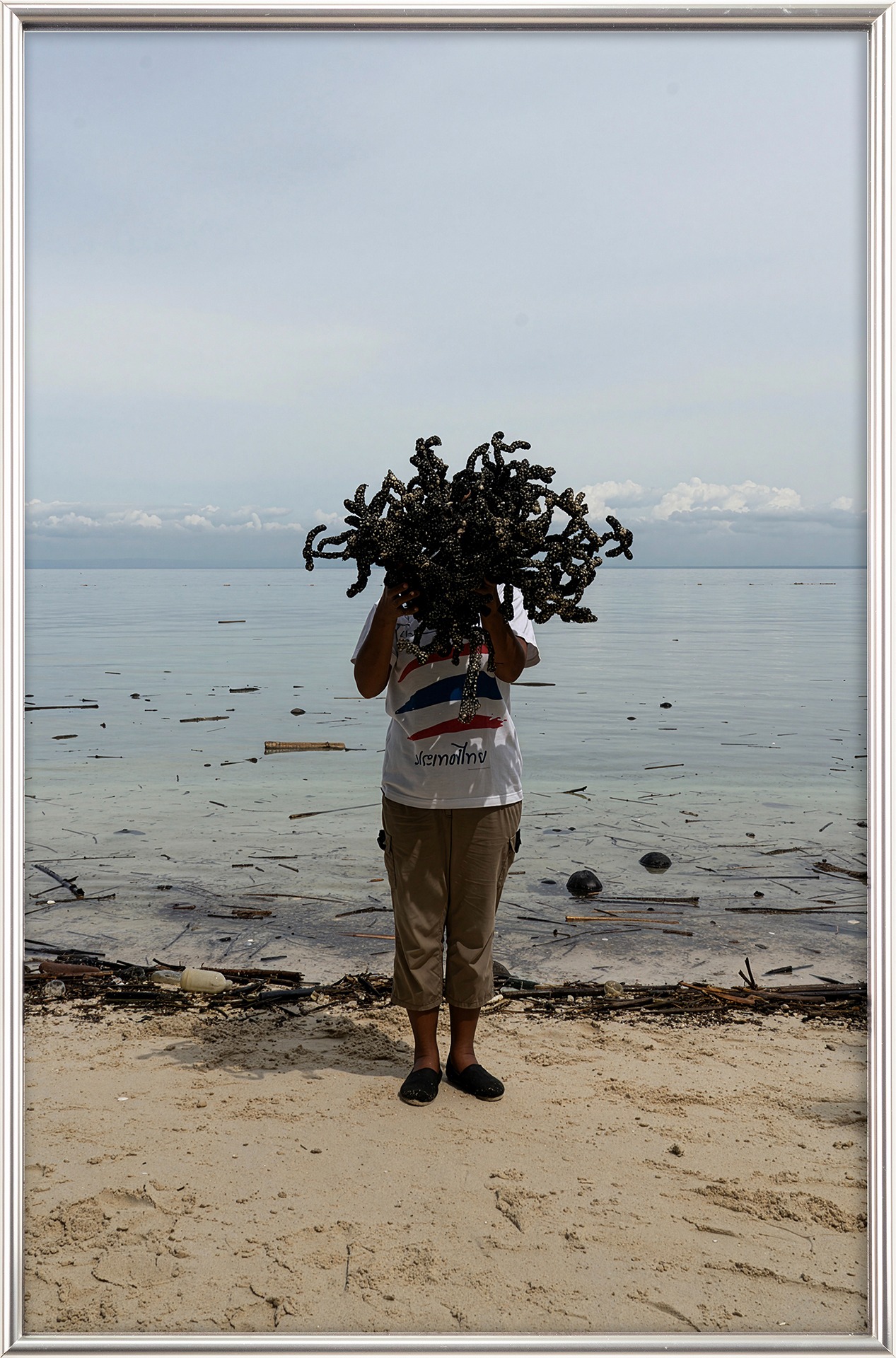

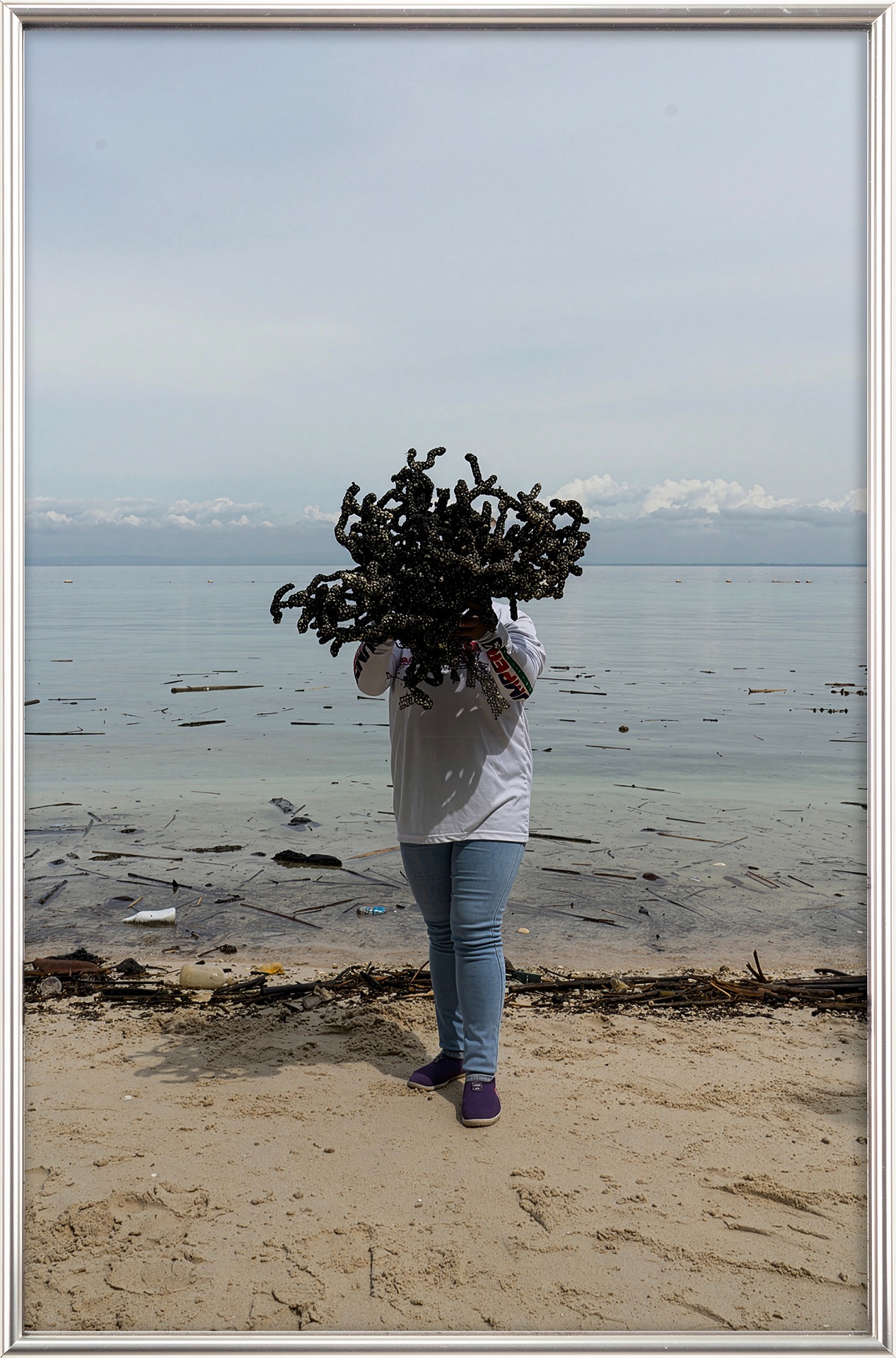

Sa mga litrato at limbag na naging palamuti sa mga pader, ay matatagpuan ang serye ng mga likha sa parehong paksa ng mga naunang mga trabaho. Mula sa isang proyekto ni Anading ay nailunsad niya ang ‘book of corals’; dito ay makikita natin ang imahe ng ilang kababaihan sa Brgy. Pindasan, Mabini, Davao de Oro, na inangat ang mga nakabalot na estruktura na koral sa kanilang mga mukha na parang pagpukaw sa mga anonymous na larawan - muling sumasailalim sa mga nakaraan niyang mga likha - upang magbigay pugay sa naninirahan sa mga baybayin at tumulong sa pagbawi at pagbalot ng mga lambat habang nagtataas ng kamalayan sa rehabilitasyon ng bahura, ang pamamaraan at pagbabagong-anyo ng mismong linikha. Dala-dala nito ang bigat ng kasaysayan sa naninirahan sa ganitong kapaligiran at sa mga nagpapagal laban sa marupok na ekosistema.

Ang pagtatanghal na lumalalim sa kababawan, lumulutang sa kalaliman ay yumakap sa mga gusot sa kalikasan kaugnay sa mga bagay na likhang-tao, dahil sa kalaunan ay mahalaga ang pakikipag-ugnay ng tao at ang masining na interbensyon na pinairal upang magmungkahi ng mga bagong pamamaraan upang muling isipin, muling itayo at marahil ang pagkukumpuni sa marupok nating mga kinalalagyan. Sa una ay nakatutok sa pagbawi - pagsisid, at pagkuha ng mga lambat - ang proyekto sa kalaunan ay umikot at nabuo sa isang pagtuklas, pagyakap sa mga bagong pamamaraan at pagkakasama ng mga materyal upang ibahagi ang bagong wika na magtutulay sa puwang ng mga pwersa na nakapagbubuo, at ng mga pwersa na nakapagbubuwag, sa panahon na hindi maiiwasan ng ano mang anyo ng buhay na namamalagi sa balat ng lupa. Sa isang banda, ang pangitain ni Poklong Anading ay kabalalay sa lumalagong interes sa katangian ng koral, ang mala-sanga niyang pagyabong ay sumasalamin sa isang malikhain na pagsusumikap: itong sining ay parang proseso ng pamumuhay - isang pamamaraan na nag-uugnay sa tao at sa kapaligiran, at para kay Anading, ito ang nagtatakda na landas tungo sa pagkakaisa. Hindi sa isang kumpas kundi sa sama-samang yumayabong na ritmo ng pagpapanibabago.

—Cocoy Lumbao Jr. and Eugenio Maestro

From the Lubi Art Residency Program in Davao de Oro all the way to its first iteration in his exhibition in New York, Anading’s intermingling of upcycled materials with new art expressions receives another public viewing for the residents of Metro Manila through his latest show at Silverlens Gallery. Combining discoveries from his diving forays with volunteers and marine biologists led by dive master Iñigo Taojo of Davao Gulf Divers, initiatives to restore coral reefs and their habitats, and his own exploration of materials to produce work, his new exhibition conveys a kind of “resurfacing” of some of the realities and materialities derived from the depths and nature’s encounter with consumption and artificiality.

The exhibition demonstrates the artist’s conceptual approach while using different media—objects, video, photographs, and drawings—all derived from his diving expeditions in various sites. One of his main aquatic hauls—the “ghost net,” which was used to catch fish and later to fend off trash from being swept to a nearby shore—had grown its own colonies of barnacles, coral recruits, and algae as it sat on the seabed, threatening to inflict further damage on other marine life. Anading has turned the process of removing and renewing these abandoned nets into their new form as synthetic corals, as an homage to the life forms they disrupted and as a large sculpture to accentuate the paradox of the situation—one that also uncovers the nature of art: interventions of man-made objects against a world that ultimately intervenes with everything that is man-made.

Holding on to the idea that every dive is a clean-up dive, the discovery of an abandoned fishing net became the starting point for his main work called recruit (No. 1), which appears as a large installation and a set of other wall-bound pieces in the main gallery space. The term “recruit,” derived from the Latin recrescere—re meaning “again” and crescere meaning “to grow”—suggests renewal and regeneration. The work reimagines the net as both a remnant of human impact and a potential substrate for new coral growth. It reflects on the possibility that, if stabilized against ocean currents, such nets could support corals to grow naturally over time—branching outward and catching refracted sunlight in a slow act of regeneration. It appears to come in stages, made evident through an accompanying video: the discovery of the net, its recovery and transformation, and the transference of the recruit back to the reef. Together, these elements form a visual narrative about ecological renewal, emphasizing how creative practice can participate in environmental repair and reinterpret the boundaries between destruction and growth.

We see his other works upon entering the gallery, where visitors encounter two sculptures made of stainless steel wires wrapped with fragments of plastic packaging collected from various dives. One is draped across the large wall to the left—a handmade cyclone fence—while the other appears as a coil facing the entrance, echoing the motion of water currents and the gesture of bandaging. These works open the exhibition and recall the artist’s early experiments with wrapping and binding. The theme of plastic as a human trace continues throughout Anading’s works, which is common in his previous shows and experiments—an approach first explored in the Melbourne group exhibition Normal Scheduling Will Resume Shortly (curated by Dr. Vincent Alessi) and in the work mankay (2019), where bandaging emerged as both a gesture of care and a response to damage. The word mankay, derived from Tamil for “fruit of the mango tree,” is reimagined as “fruit of man,” reflecting on human creation and residue. The idea originated from the branches of a mango tree beside the artist’s former studio, whose falling fruits and leaves once caused roof leaks. The branches were trimmed and later wrapped in discarded plastic packaging, echoing the cycle of how nature and humanity consume and produce their own fruits. When the tree was eventually felled, the act became both offering and mourning. The theme of plastic as a trace of human presence persists in this exhibition through the use of ghost nets as well.

In the photographs and prints that adorn the walls, we encounter another series of works on the same subject. From a project Anading created called book of corals, we see the figures of several women of Brgy. Pindasan, Mabini, Davao de Oro, who have lifted the wrapped coral structures against their faces as if to evoke “anonymous” portraits—again a reflection of Anading’s past works—in order to pay tribute to the locals who lived along the coastline and helped retrieve and wrap the nets while also raising awareness about reef rehabilitation, the process, and the transformation of the material itself. This carries with it the weight of history as the living residents of such environments and as the laborers who continue to toil against the fragile ecosystem.

The show, lumalalim sa kababawan, lumulutang sa kalaliman, embraces the entanglements of nature with man-made objects and, ultimately, the human engagement needed and the artistic intervention deployed to come up with new ways to reimagine, rebuild, and maybe even repair our fragile habitat. Initially focused on recovery—diving, collecting, and retrieving nets—the project has evolved into discovery, drawing out new processes and combinations of materials to communicate a new language for bridging the gap between constructive and destructive forces that at times seem inevitable in whatever life form one may find on this Earth. In a way, Poklong Anading’s new vision is in parallel with his growing interest in the characteristics of corals, whose branch-like growth could mirror a kind of creative endeavor: that art is also a living process—a process that links humans with their environment, and which, for Anading, marks the path toward harmony not as a single gesture but as a collective, evolving rhythm of renewal.

—Cocoy Lumbao Jr.

Poklong Anading (b. 1975, Manila, Philippines; lives and works in Manila) works with a wide range of mediums and is acclaimed for his pieces that investigate photography and travel. Fascinated with the process of creation and permutation, Anading explores different mediums to engage with a range of sociopolitical and environmental questions. Having begun his career as a painter, he is not driven by an overt agenda, but prefers to let his mind wander, thinking with and through his materials as they undergo their transformations. He frequently uses found objects and discarded materials that lead him to investigate notions of worth and value, and to explore what it means for art to exist inside and beyond capitalist production.

Anading has completed residencies with Big Sky Mind, Manila, Philippines (2003 to 2004), Common Room, Bandung, Indonesia (2008), Bangkok University Gallery, Thailand (2013), Selasar Sunaryo Art Space, Bandung, Indonesia (2013), Philippine Art Residency Program - Alliance Francaise de Manille in Cite Internationale des Arts, Paris, Centre Intermondes, La Rochelle in France (2014) and das weisse haus, Vienna Austria (2018). He had solo exhibitions in Galerie Zimmermann Kratochwill, Graz, Austria (2010 and 2012), Taro Nasu in Japan and Athr Gallery in Jeddah (2016), 1335MABINI in Manila, Philippines (2013, 2015 and 2017). He has been included in notable group exhibitions such as: Gwangju Biennial, South Korea (2002 and 2012), No Country: Contemporary Art for South and Southeast Asia, the first exhibition of the Guggenheim UBS Map Global Art Initiative in New York, Hong Kong and Singapore (2013 to 2014), 5th Asian Art Biennial: Artist Making Movement, National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts, Taiwan (2015), The Shadow Never Lies, Minsheng Art Museum, Shanghai, Afterwork, Para Site, Hong Kong, China and in the Architecture Biennale for the 15th International Architecture Exhibition, Philippine Pavilion: Muhon: Traces of an Adolescent City at Palazzo Mora, Venice, Italy (2016), Constellations, Photographs in Dialogue, SFMOMA, California, USA (2021) and Living Pictures: Photography in Southeast Asia at National Gallery Singapore (2022).

Installation Views

Works

SLABPAN121

SLABPAN122

SLABPAN120

SLABPAN125

SLABPAN118

SLABPAN117

SLABPAN119

SLABPAN123

SLABPAN126

SLABPAN105

SLABPAN124