About

“Inherent vice, also known as inherent fault, is the tendency in an object or material to deteriorate or self-destruct because of internal characteristics.” (American Institute for Conservation)

Silverlens proudly presents Inherent Vice, Stephanie Syjuco's solo debut in the Philippines, on view from 29 August to 5 October 2024 at Silverlens Manila.

Stephanie Syjuco has spent the past 5 years exploring American museums and institutional archives for representations of the Philippines during the American occupation. Cognizant of the way that the seemingly neutral documentary photograph was a powerful tool in the colonial enterprise, her work attempted to deny the colonizers control of the narrative, disrupting the image to foreground the lost agency of the subjects.

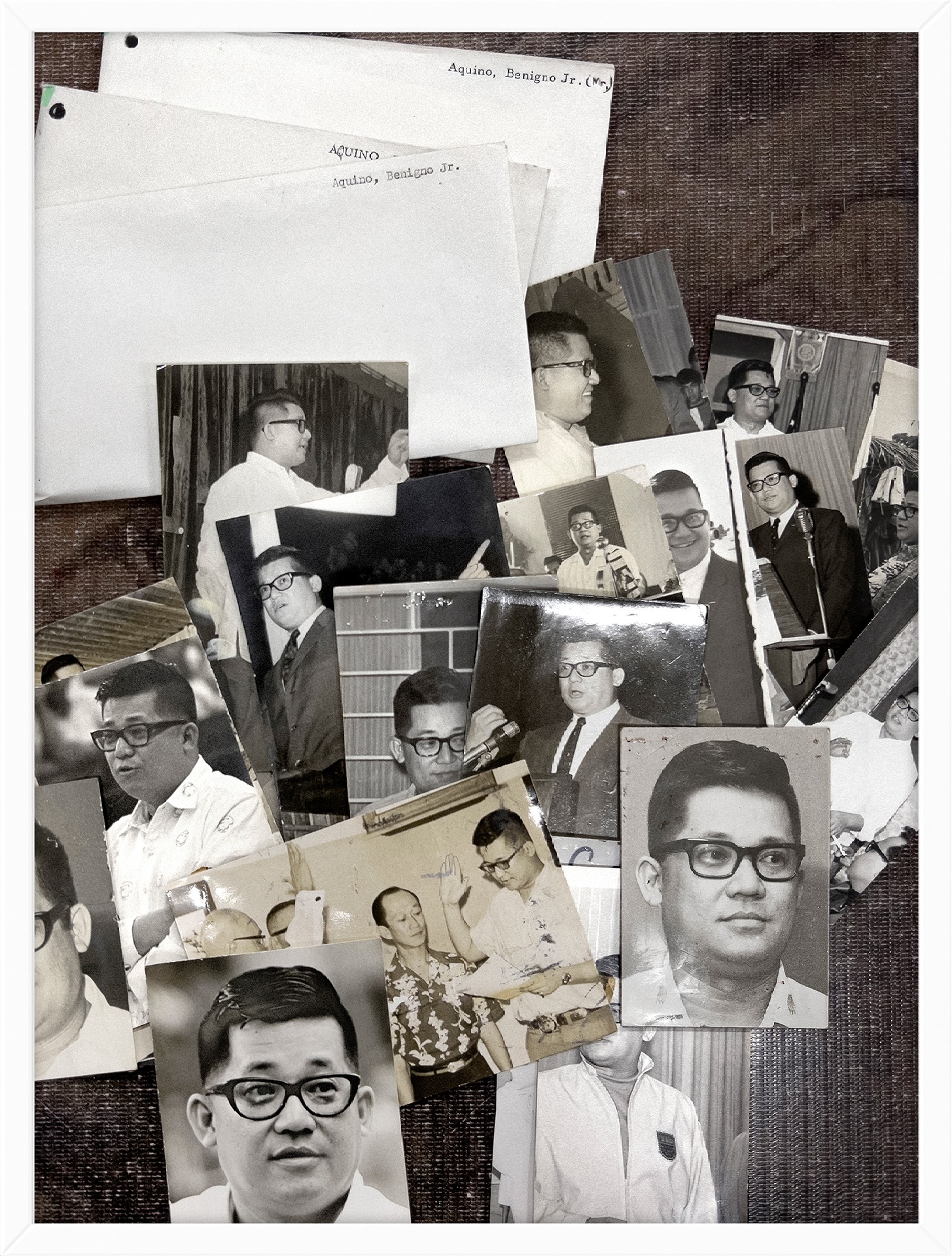

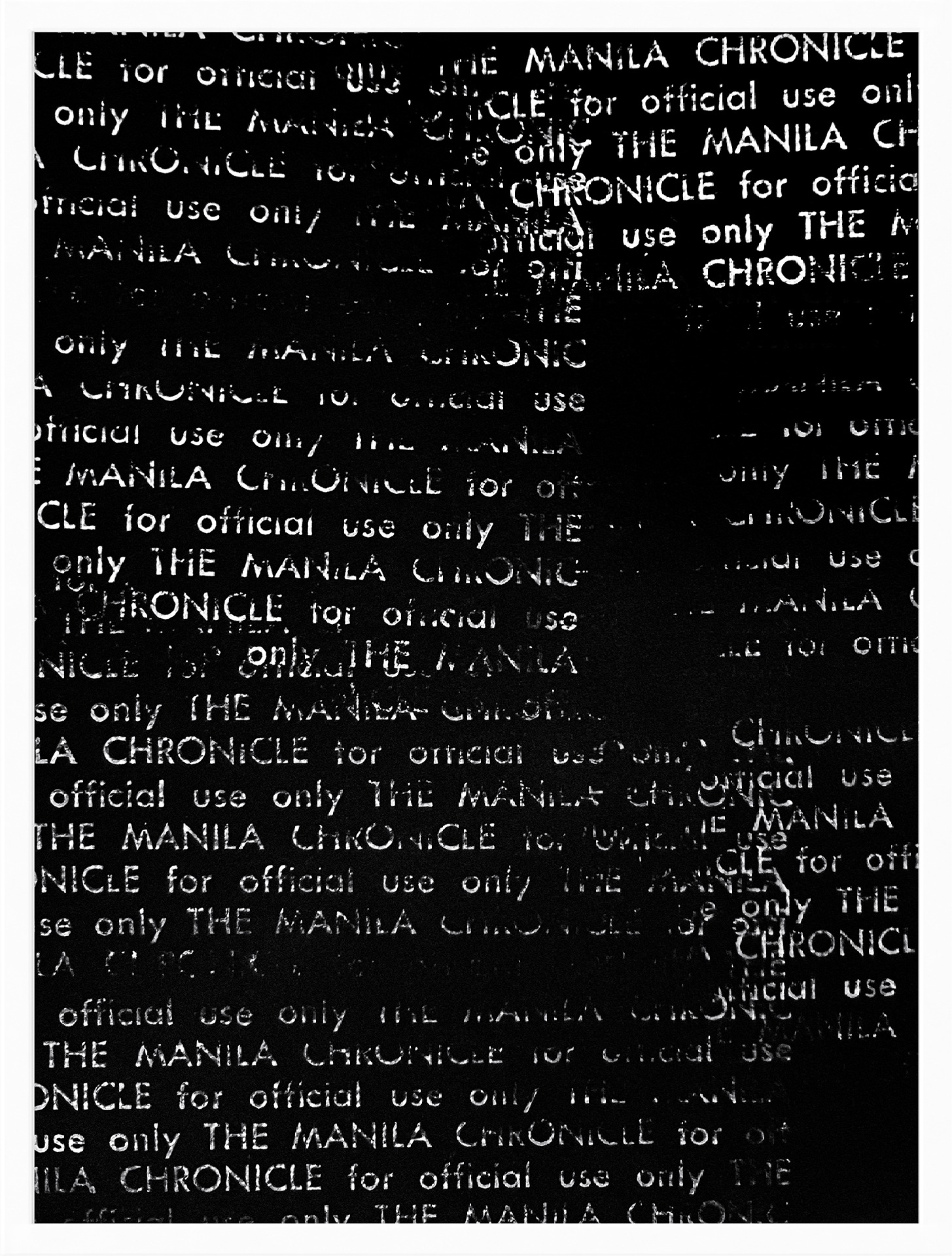

Aware of the potential of the artifacts in the Lopez Museum and Library (LML) to deepen her investigation into Philippine materials, she was invited to delve into its collection. From Filipiniana holdings that span manuscripts and maps from the 1600s to periodicals and photographs of the 20th century, Syjuco zoned in on a period from the more recent past. She worked with envelopes filled with pictures from the late 1960s to 1972 in the photo-morgue of the now defunct Manila Chronicle newspaper. The publication ran from 1945 to 1972, a period romantically remembered as the “Golden Age of Philippine Journalism.”¹ Unlike the American colonial archives, the Manila Chronicle photo morgue is a repository of materials by Filipinos, for Filipinos, not the exhibitionary other.

For Syjuco, the images she encountered go beyond a means of remembering; they become signifiers of attitudes and behaviors.

In her artist’s notes she writes:

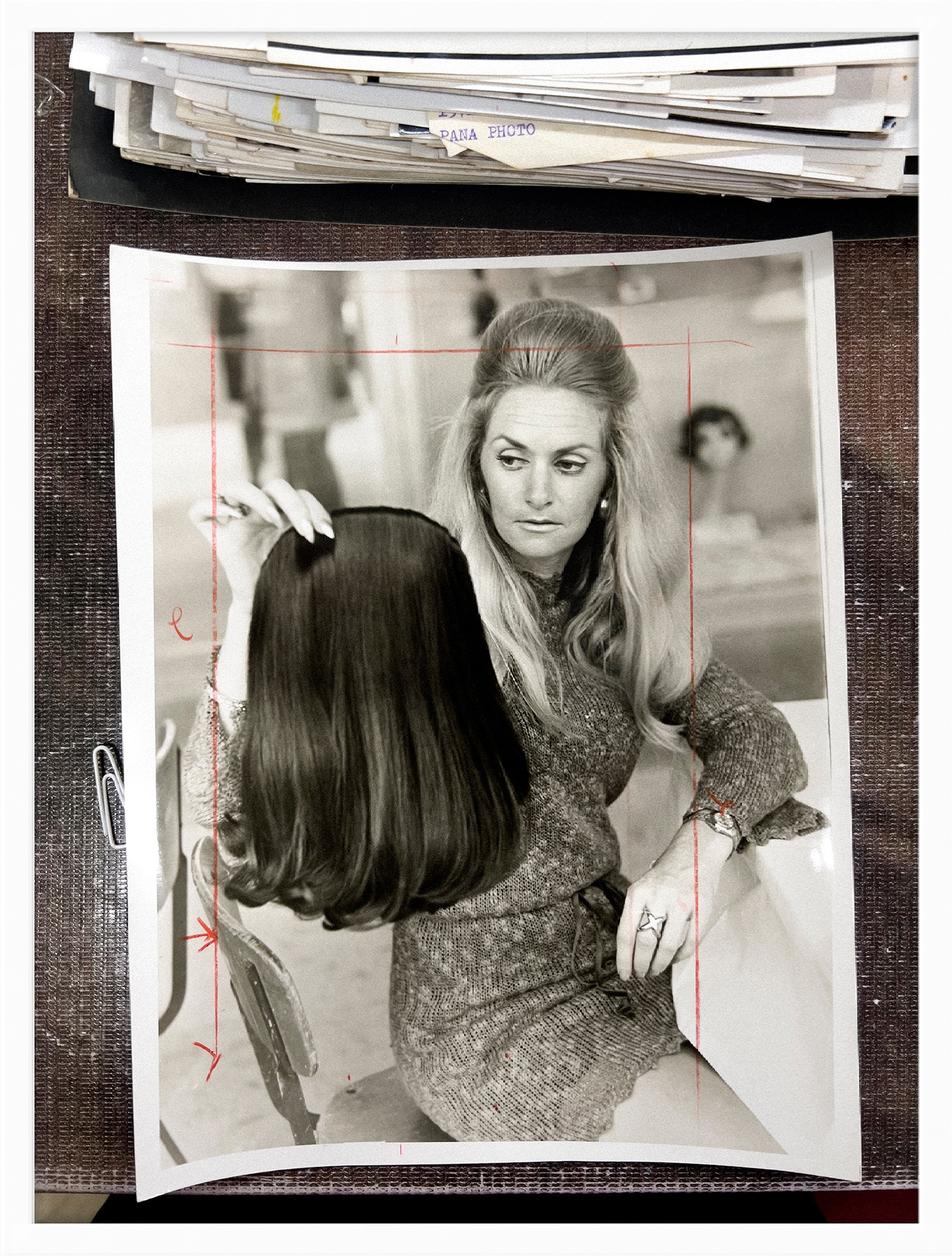

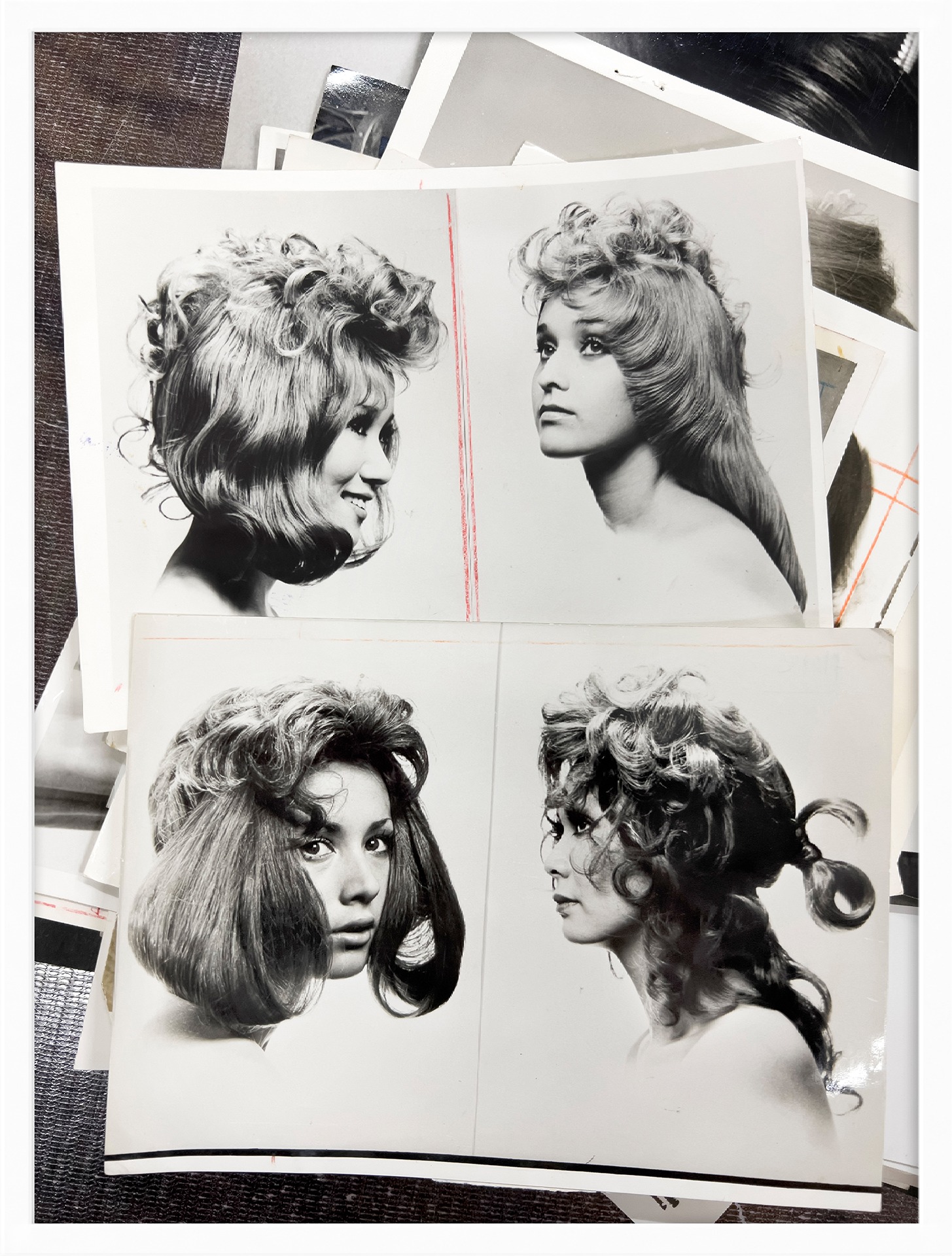

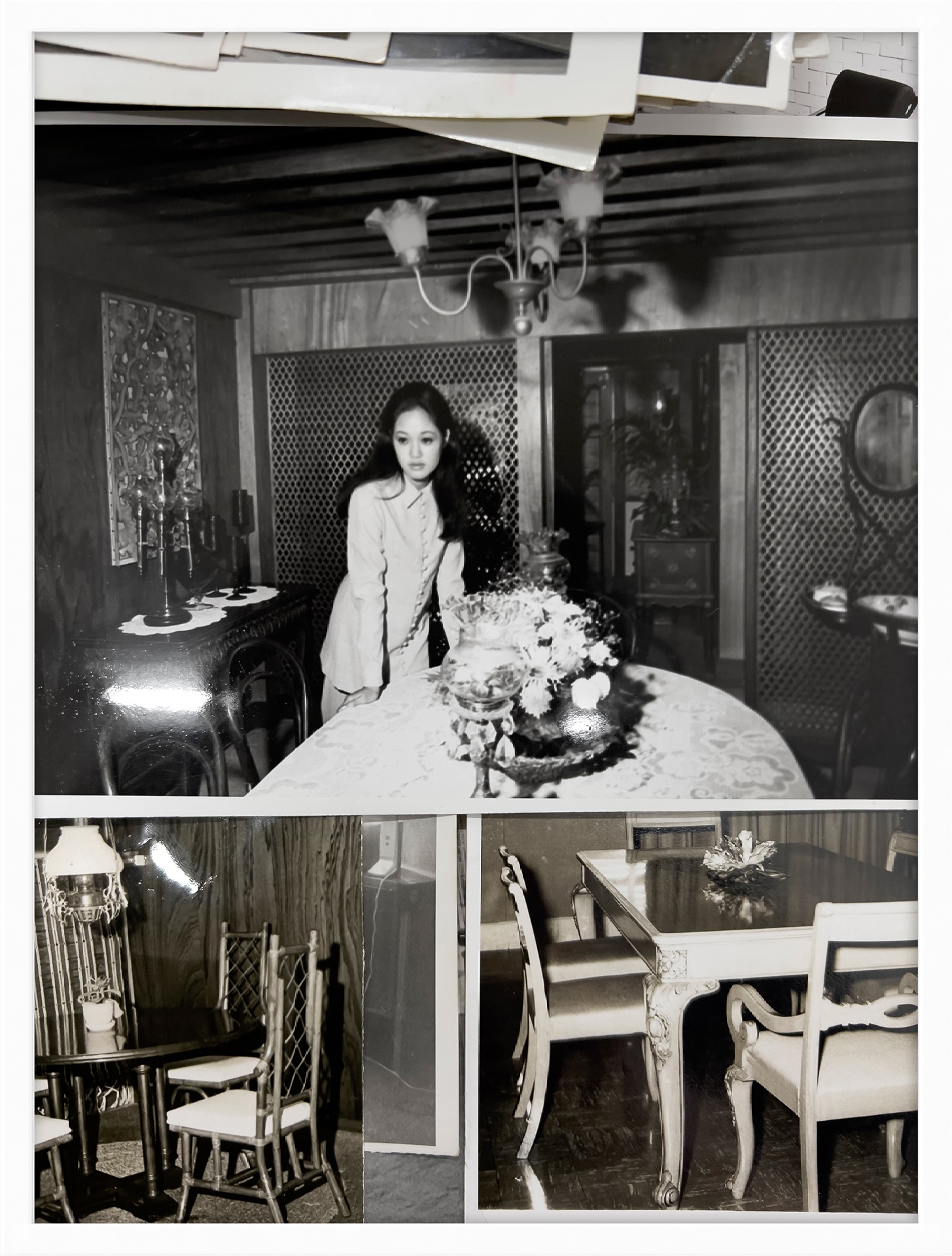

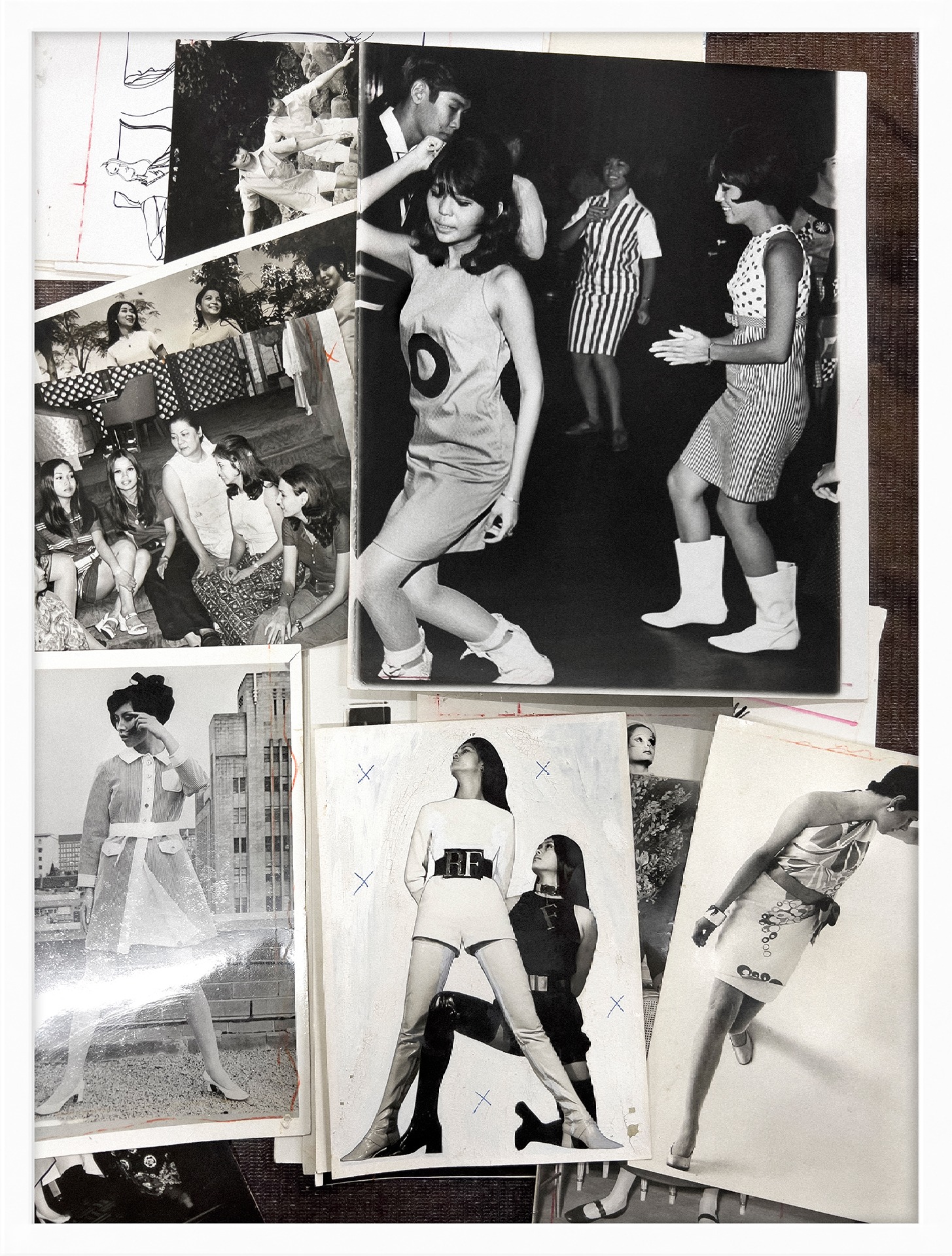

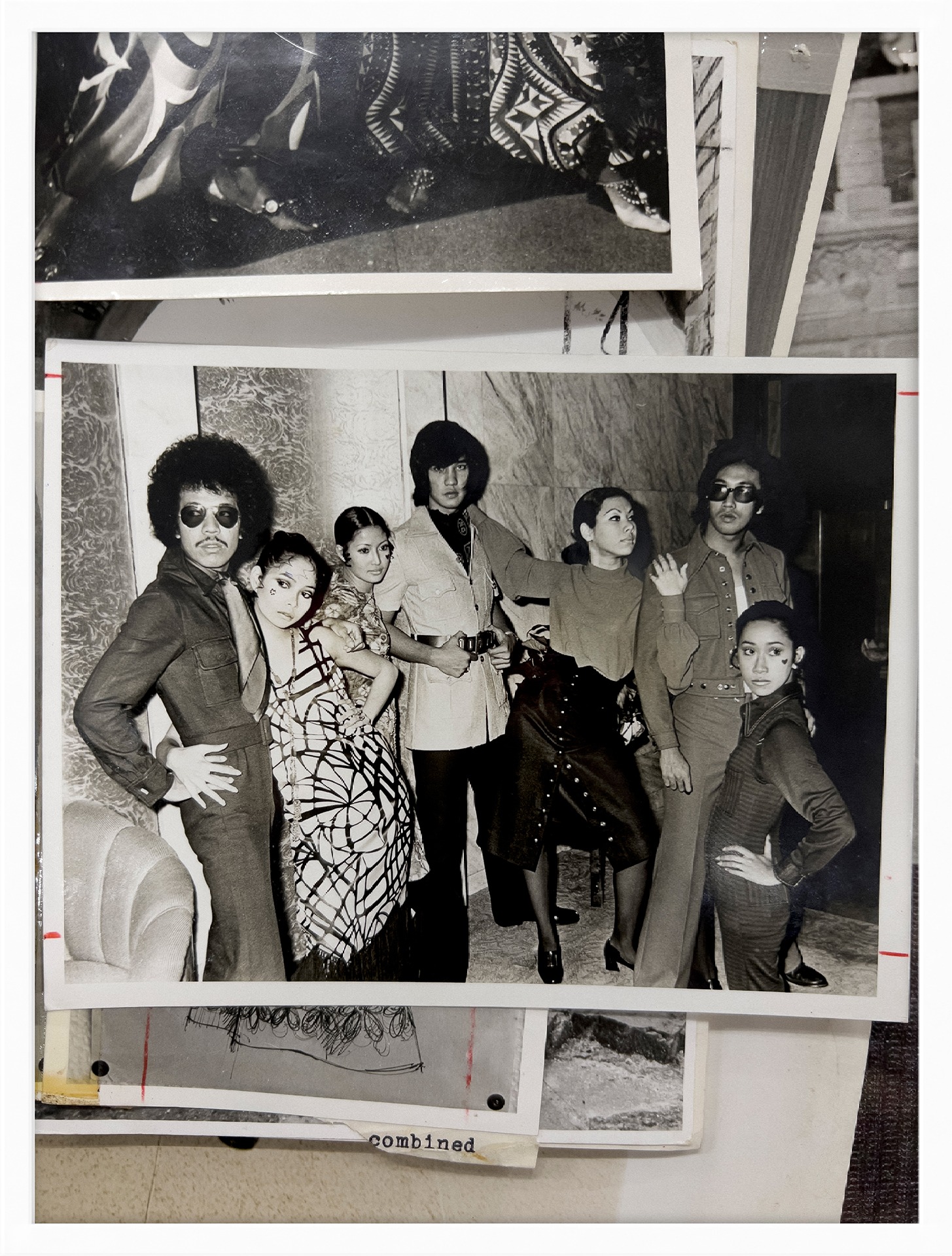

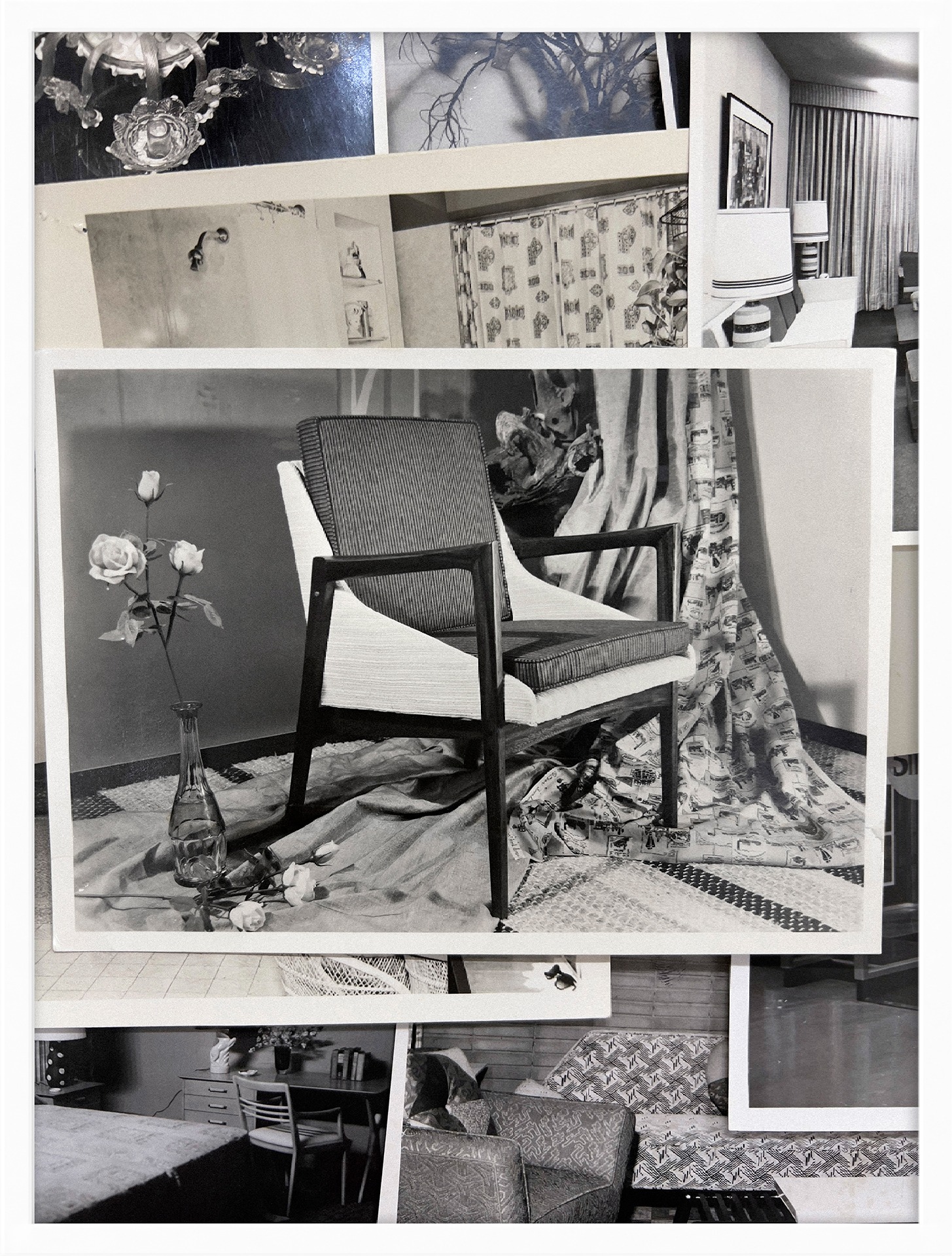

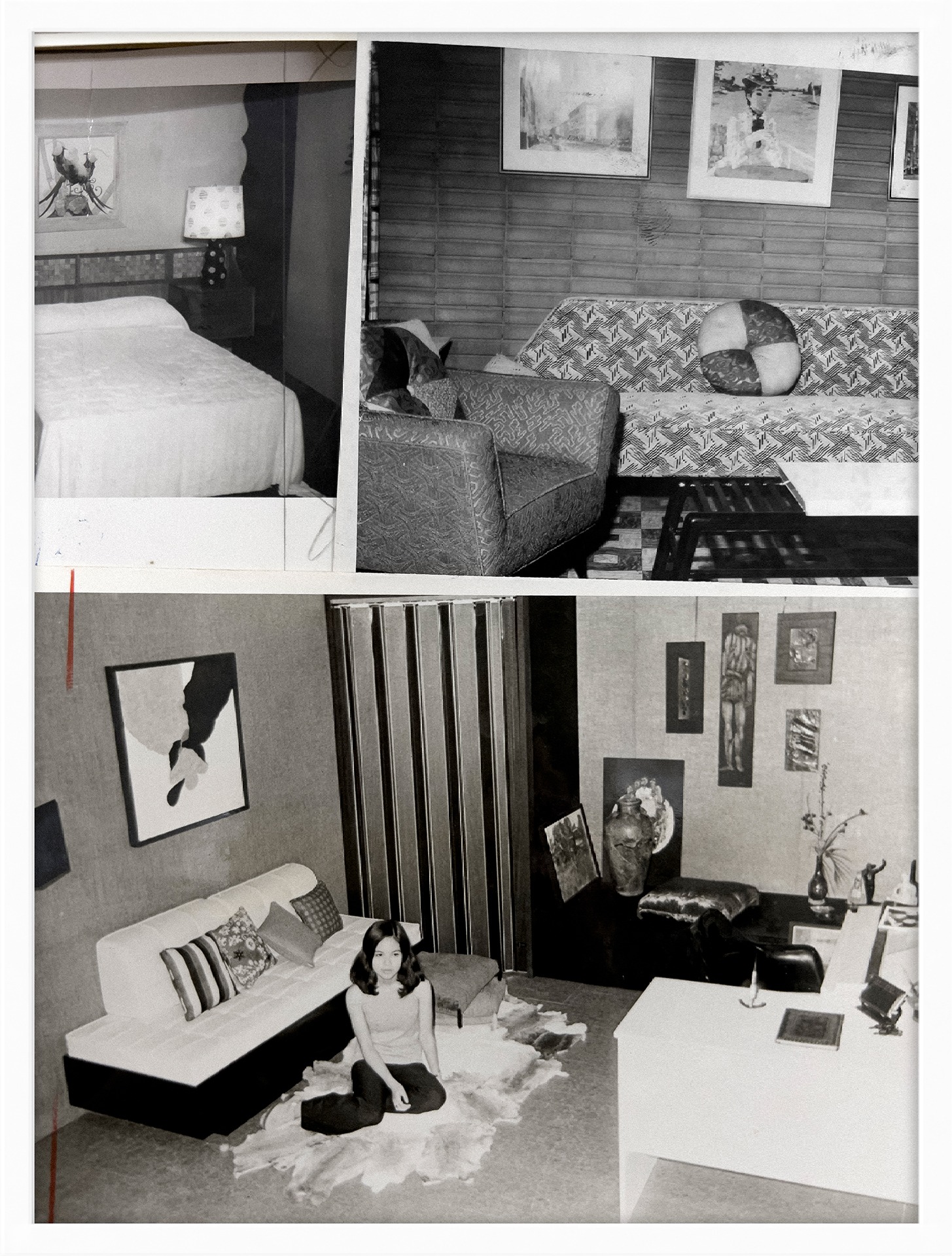

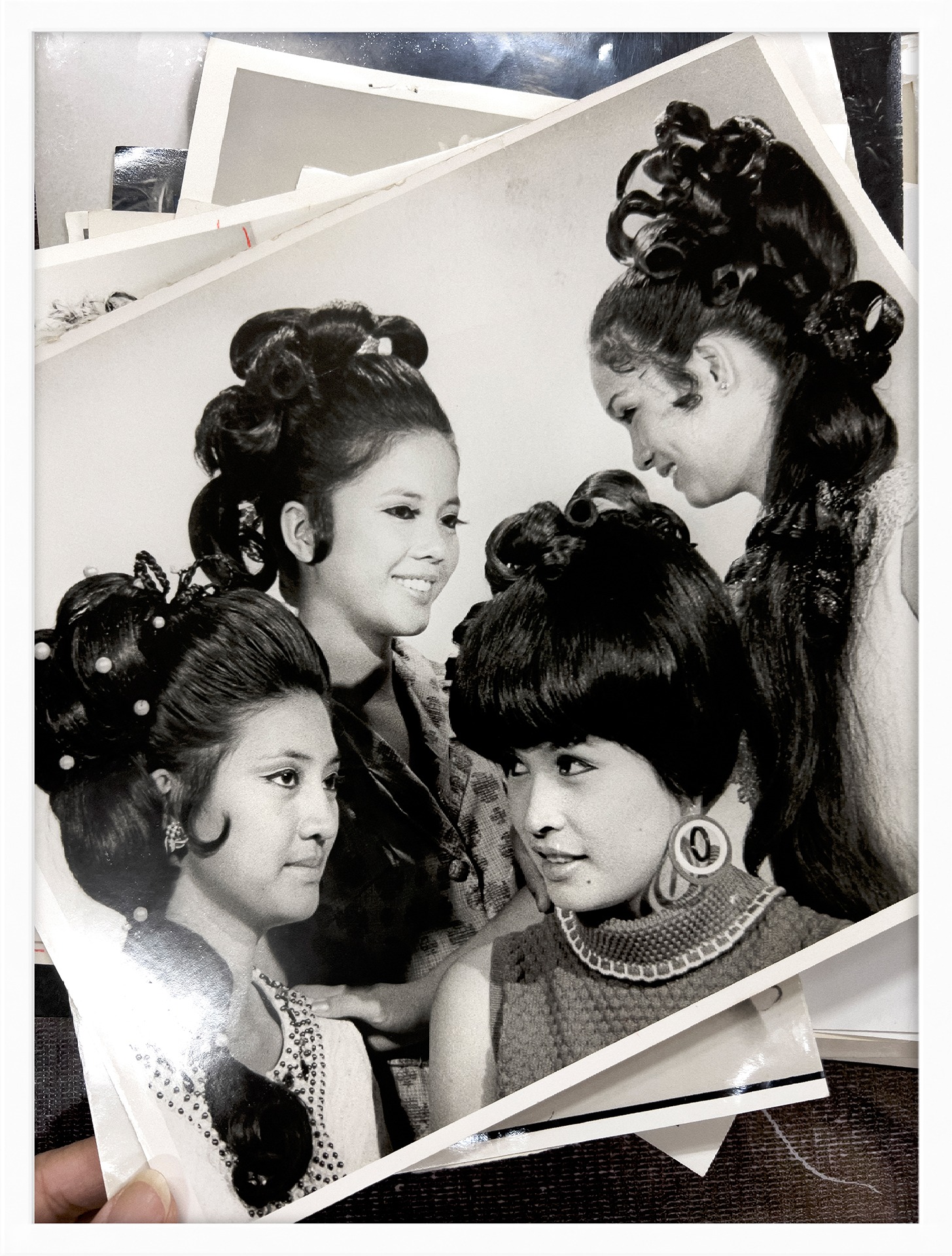

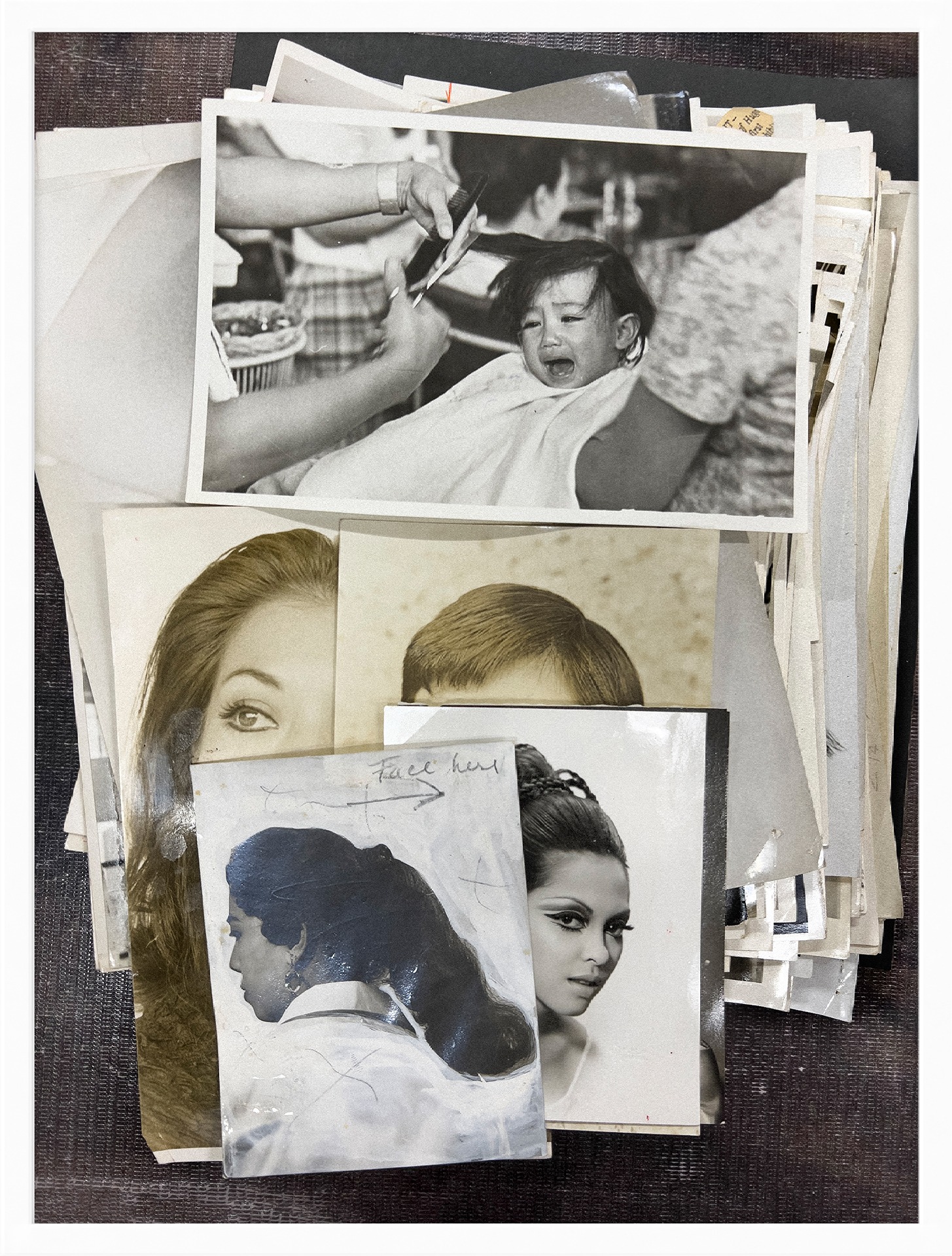

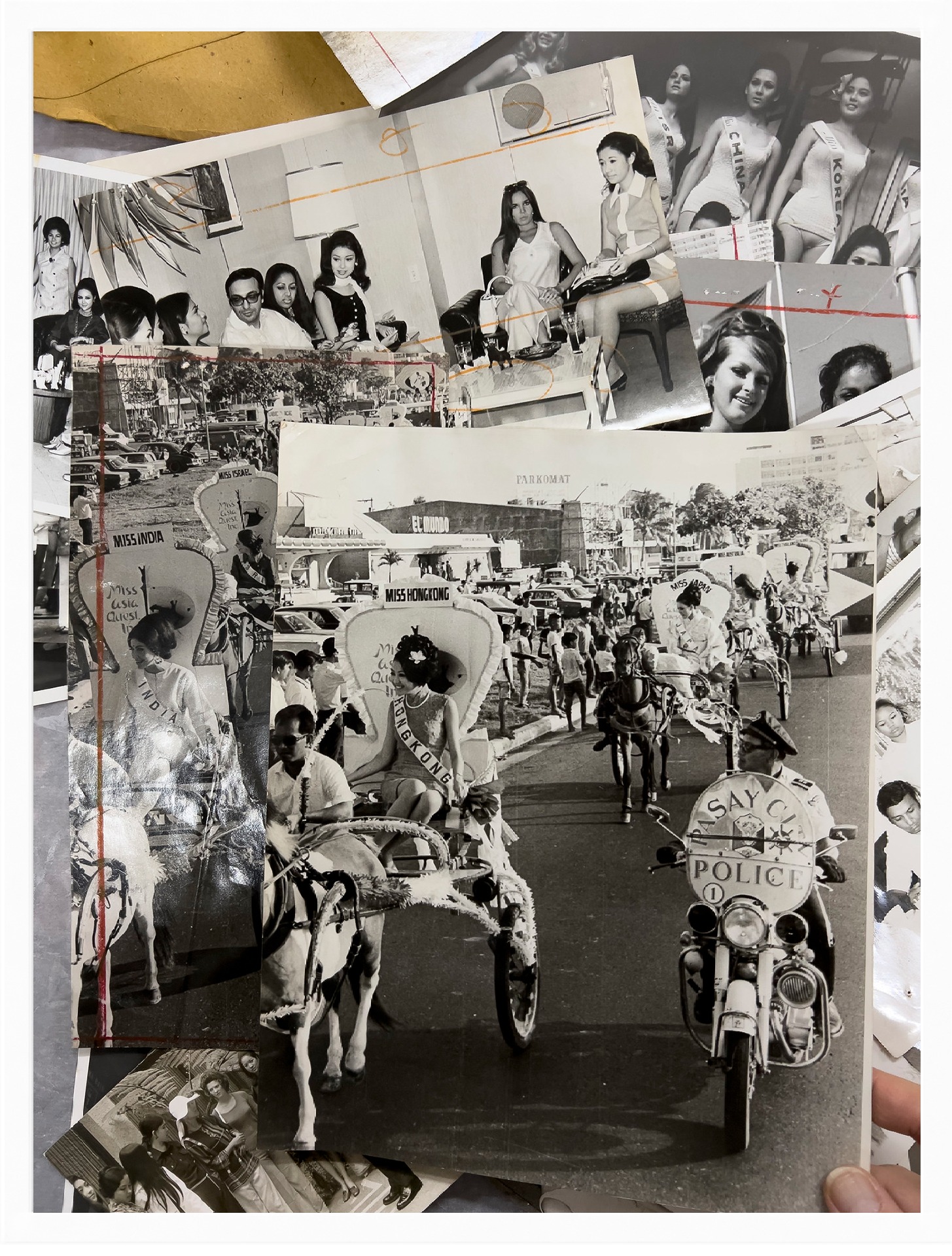

• Hair, ornament, beauty queens, furniture, and home decor: as metaphor of opulence and cosmopolitanism (and also privilege). Beauty and culture as political veneer and also as a sign of globalized culture.

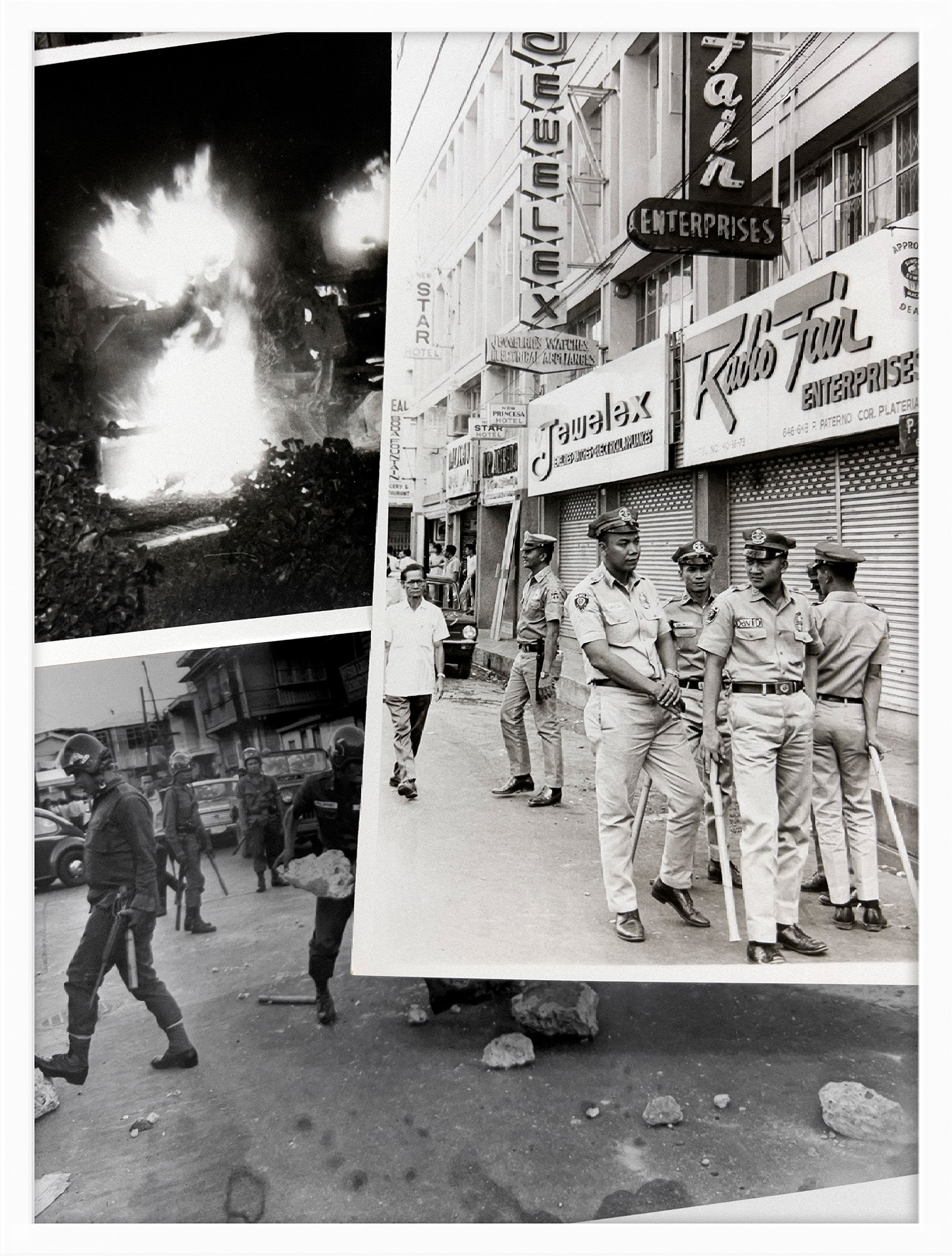

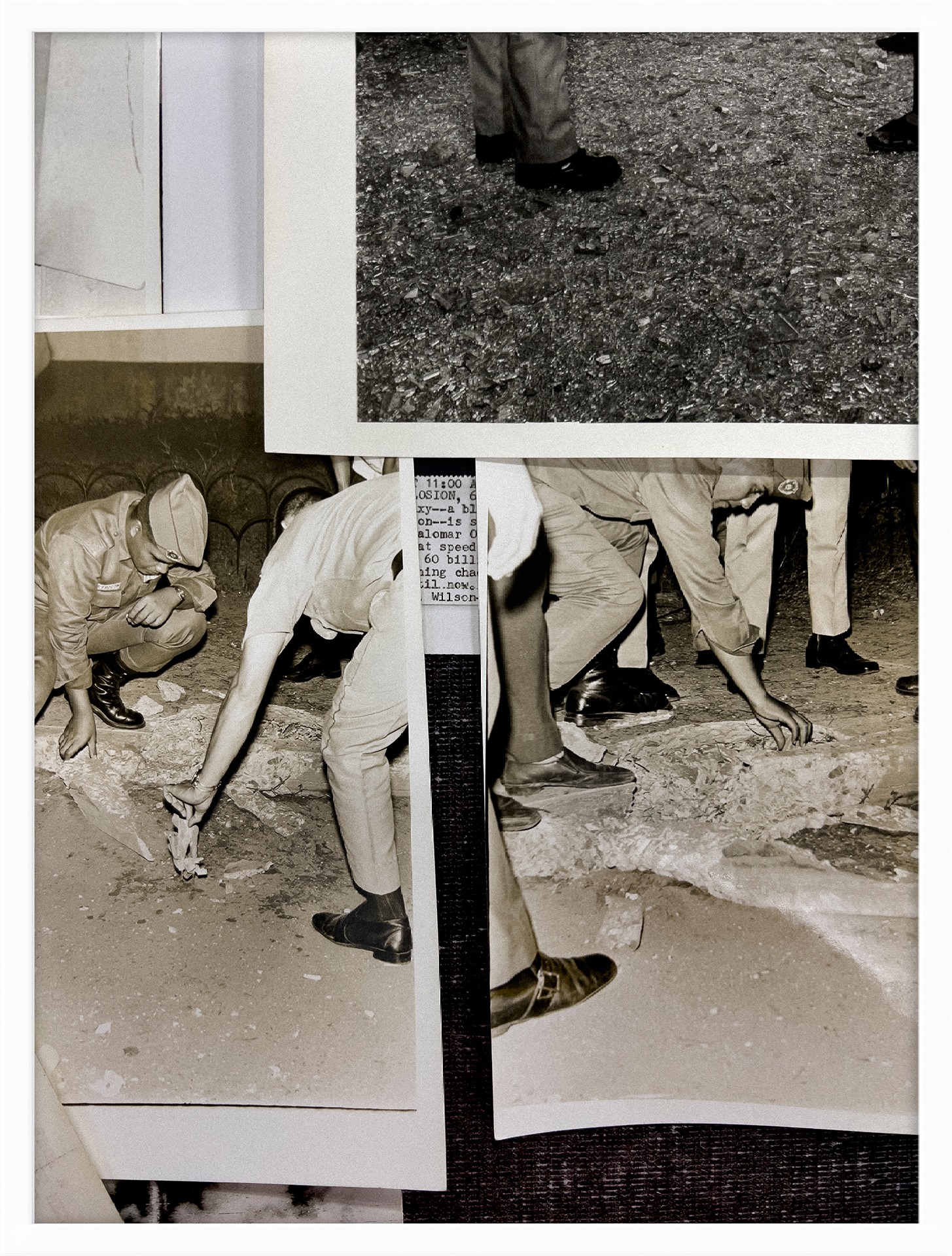

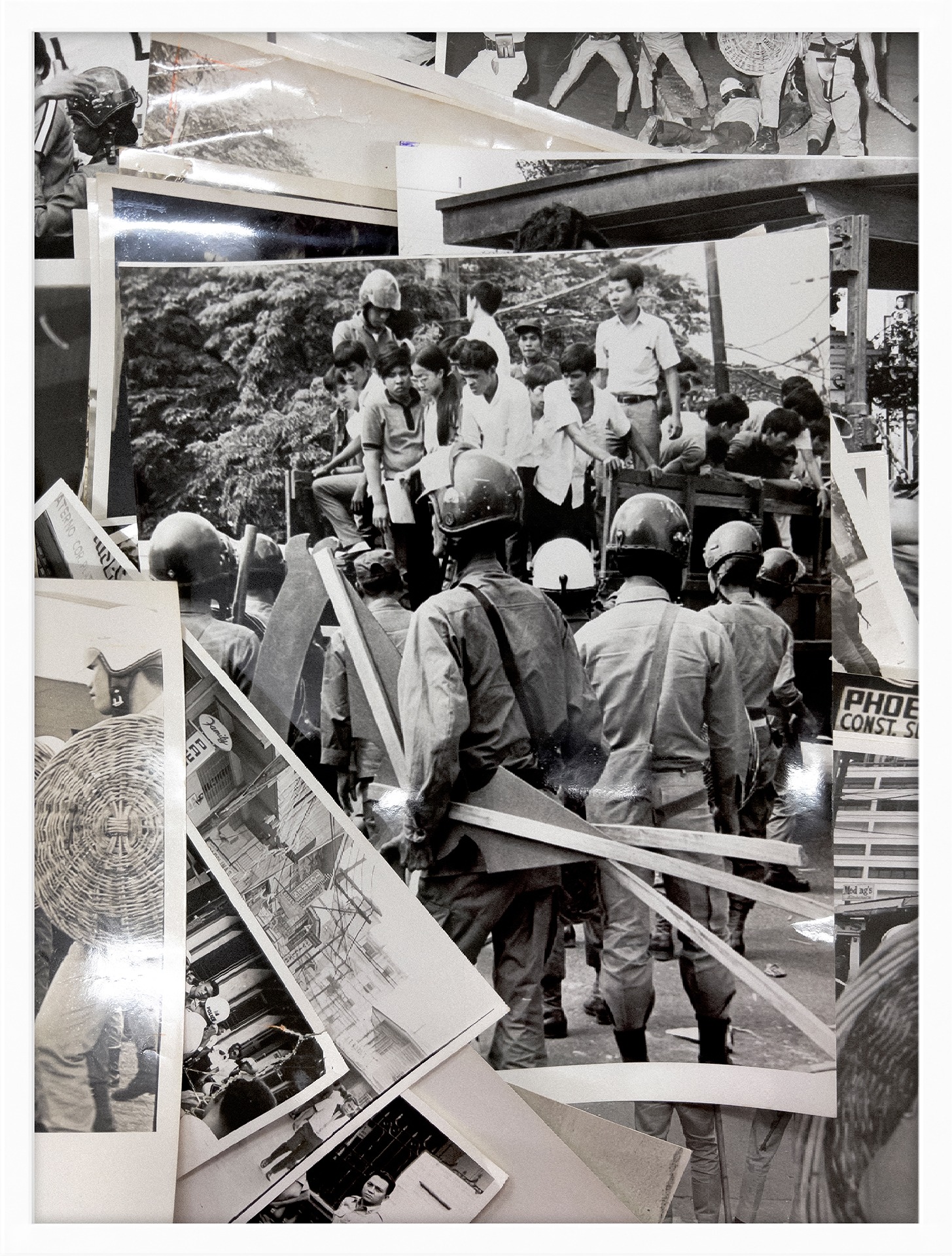

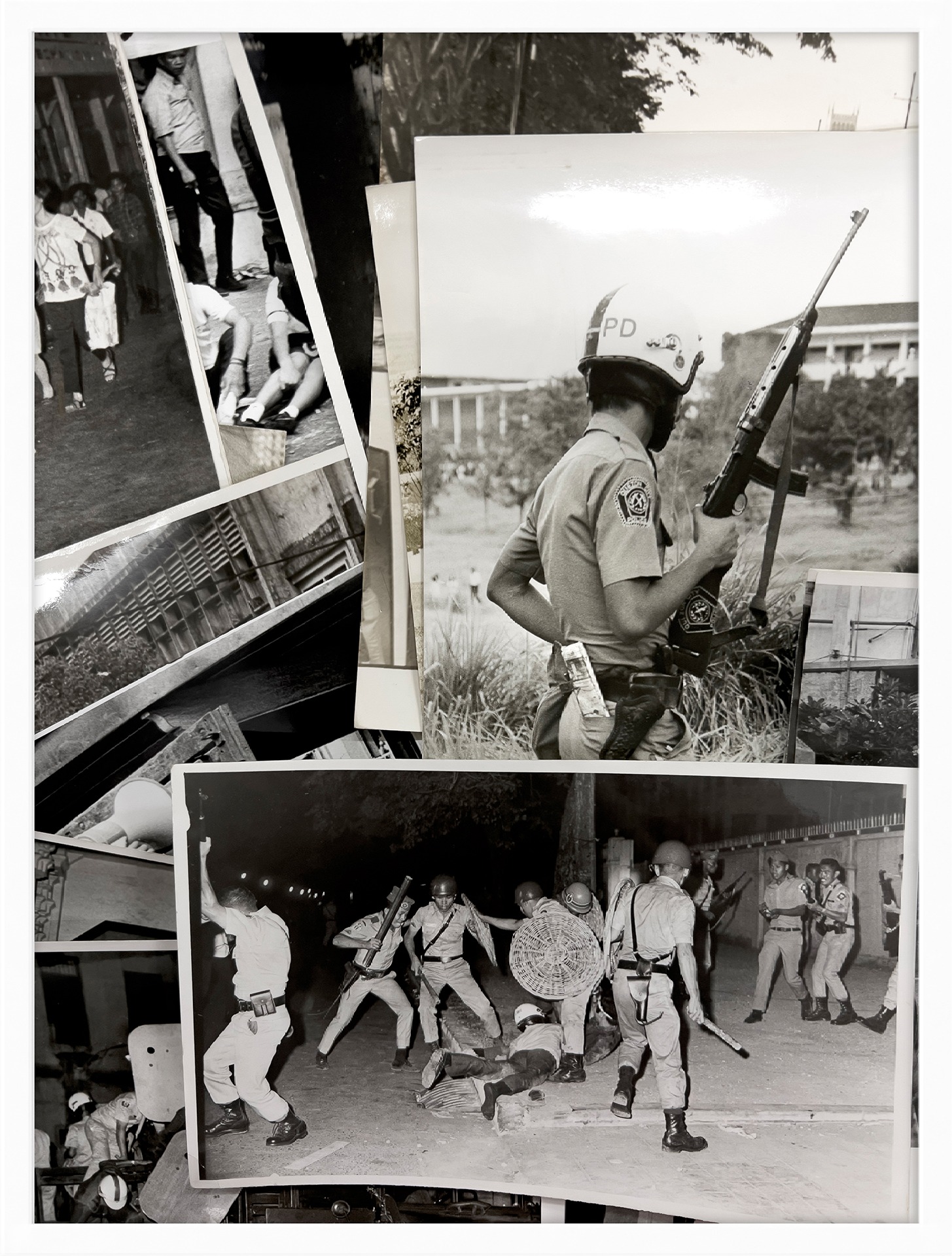

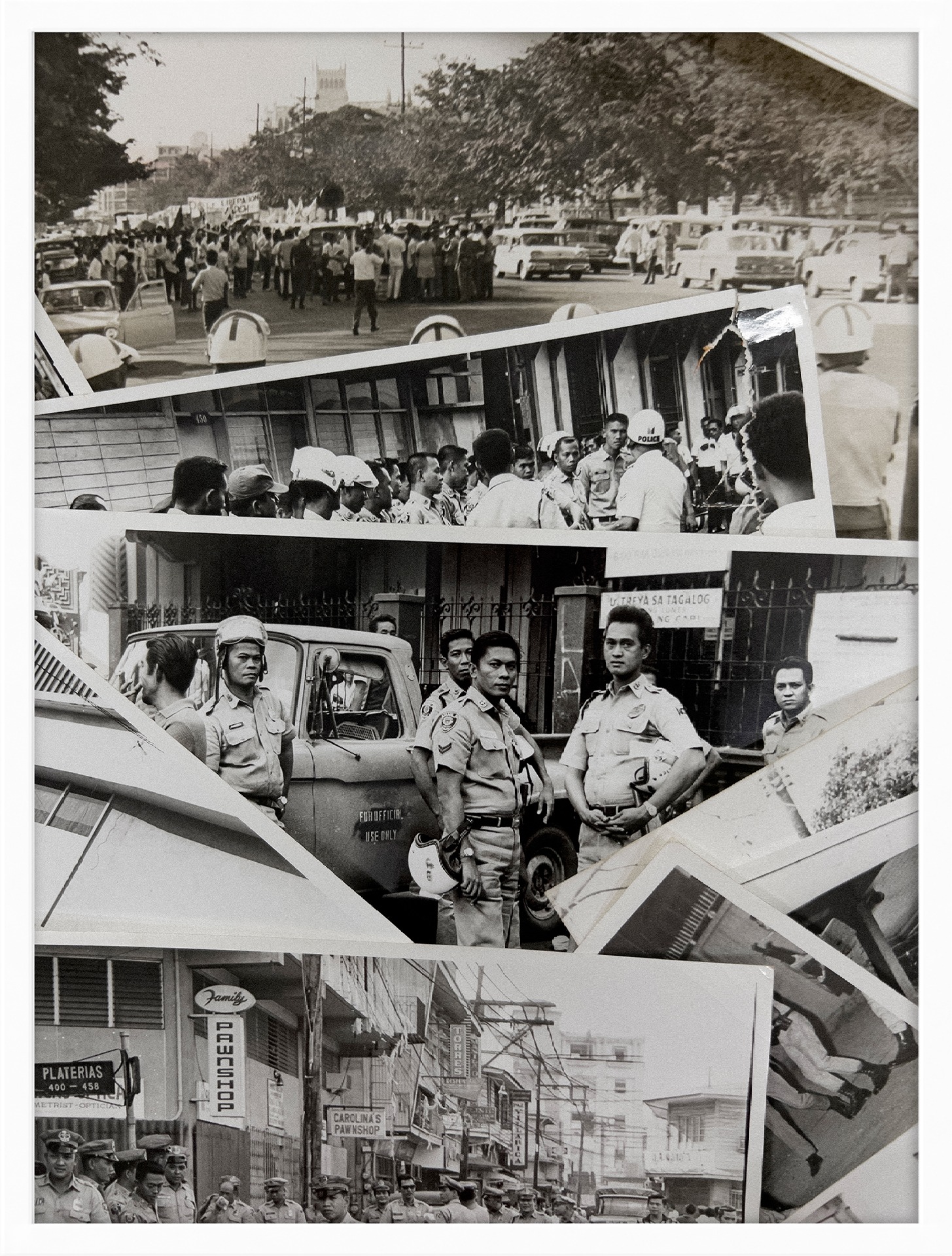

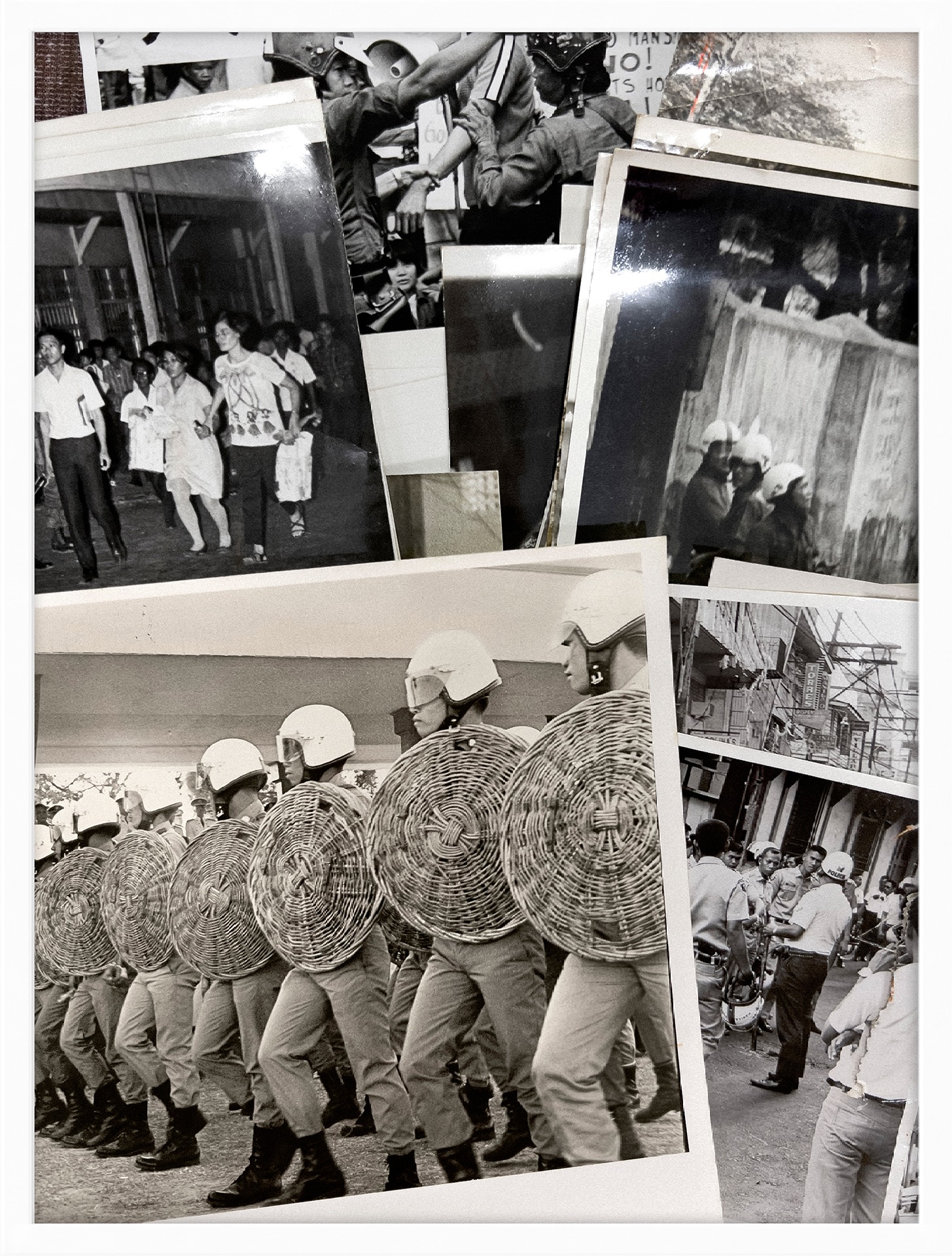

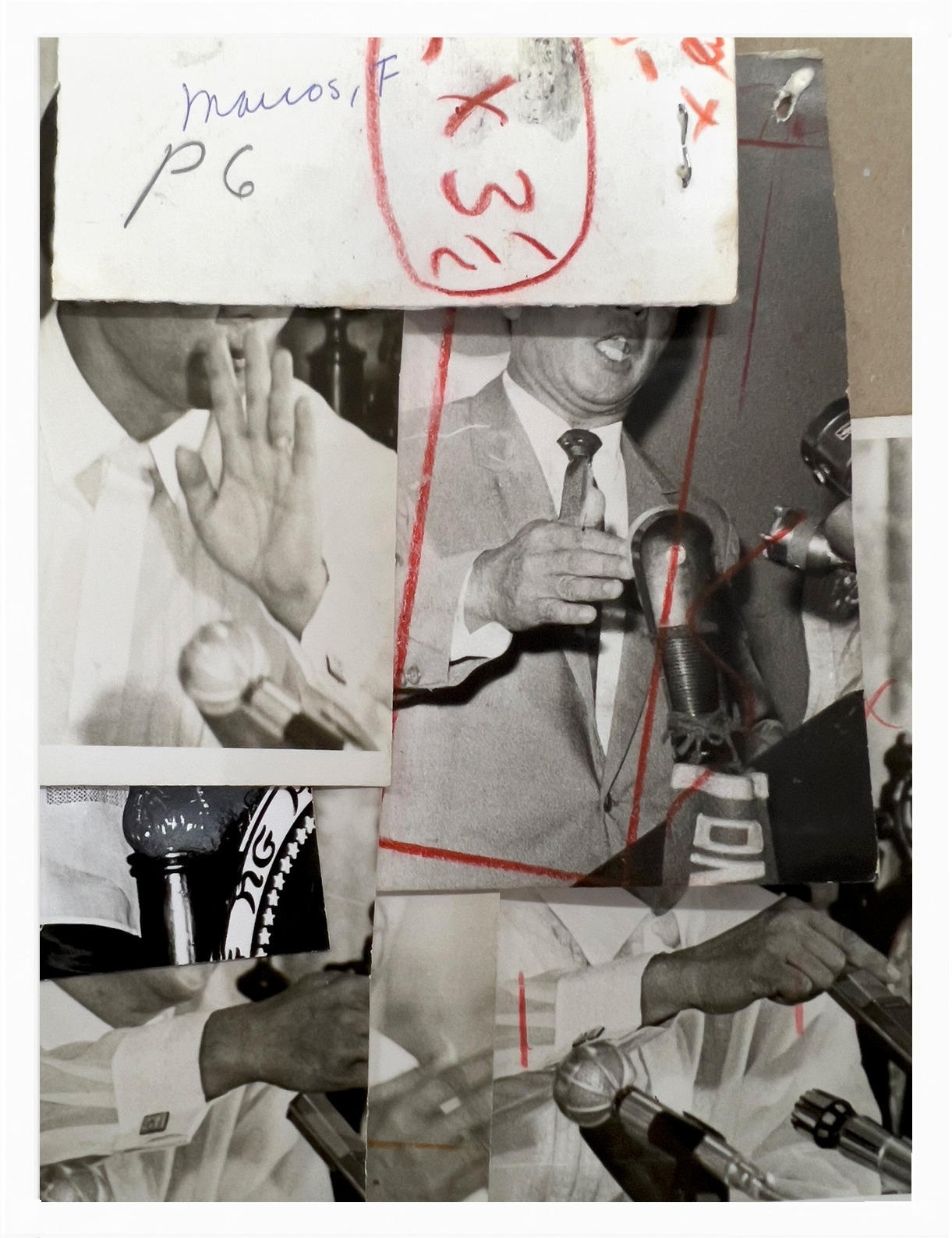

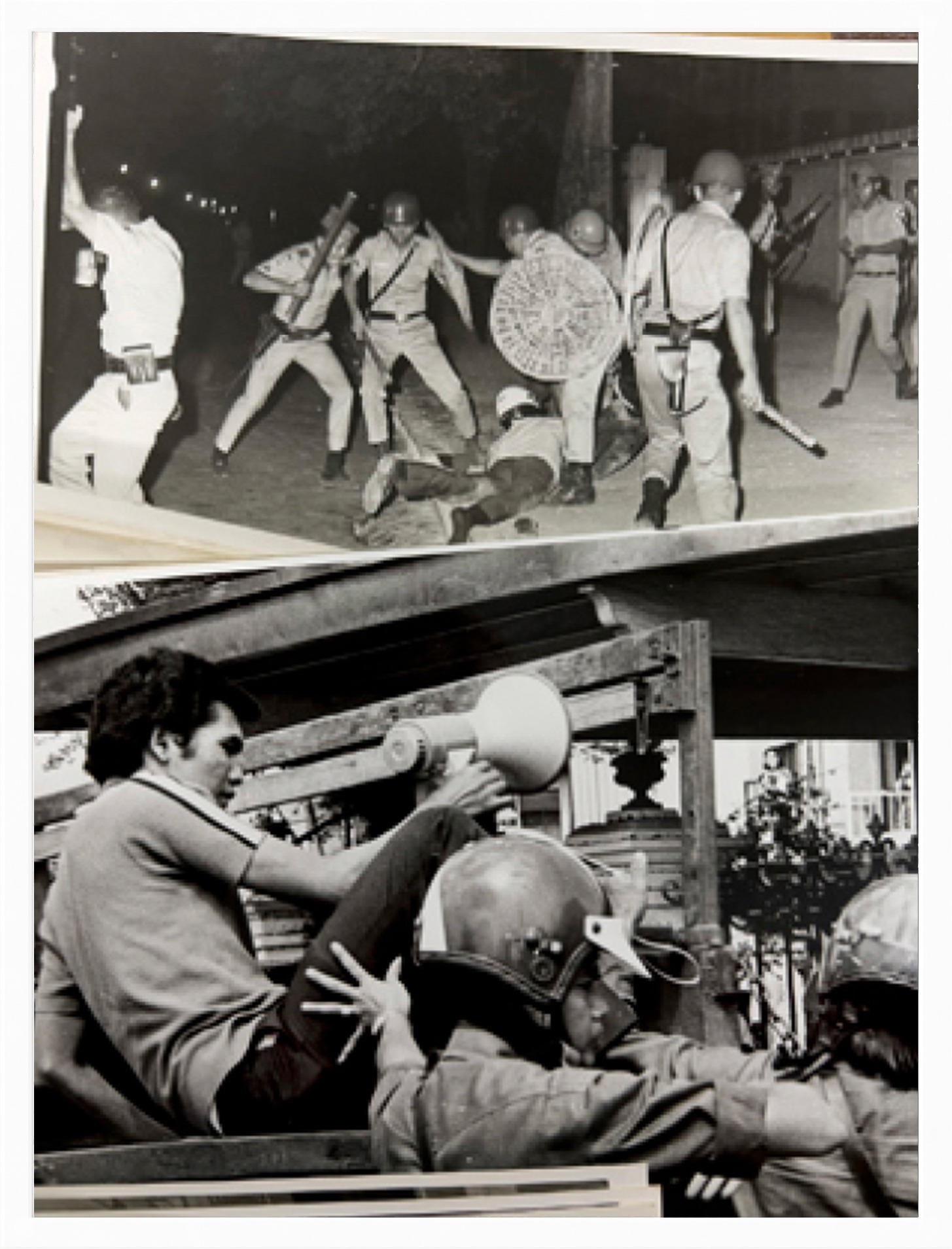

• Police / authority figures: watching, waiting, lurking, striking. Arm of the government, impending authoritarianism, surveillance and suppression in the midst of a cultural flowering

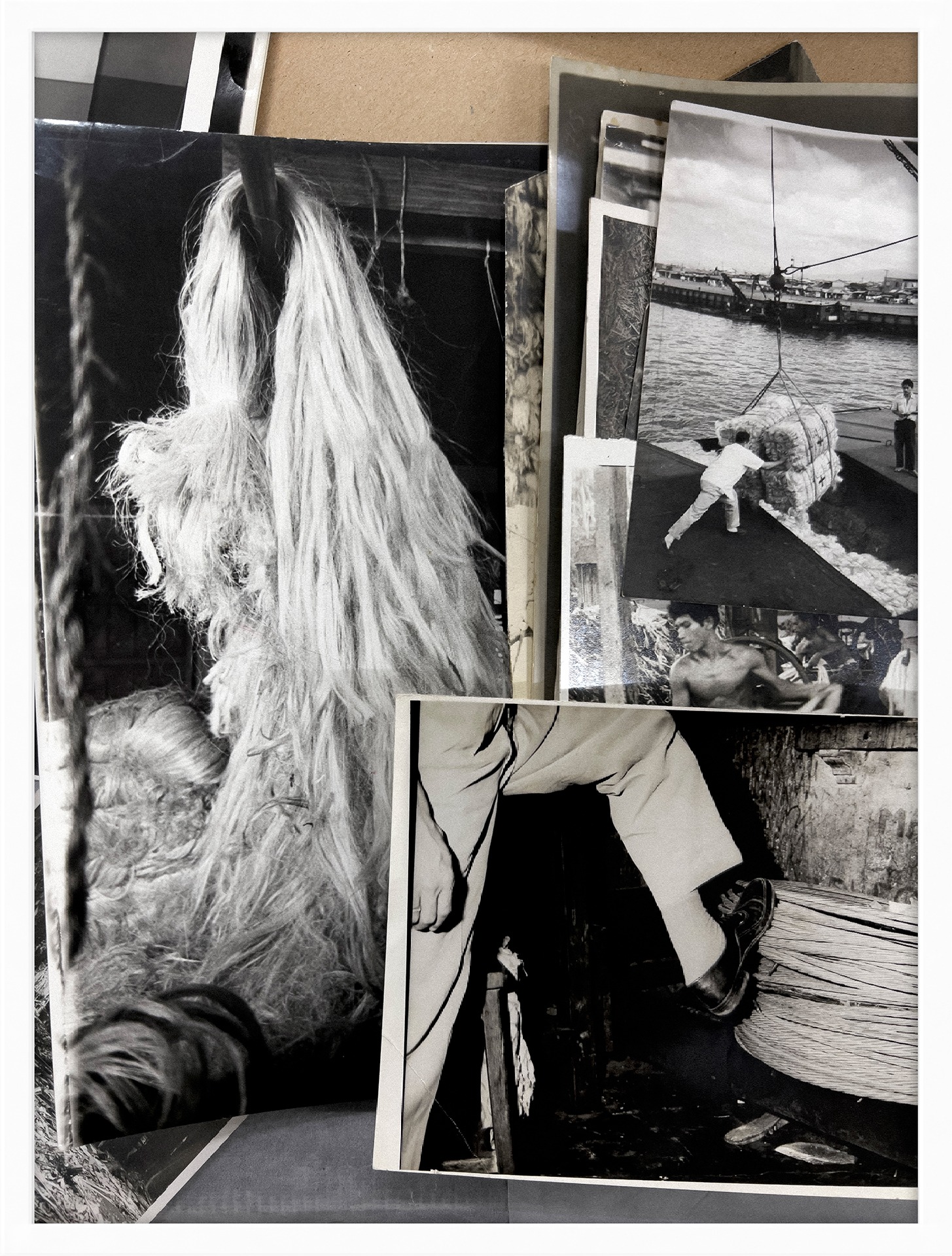

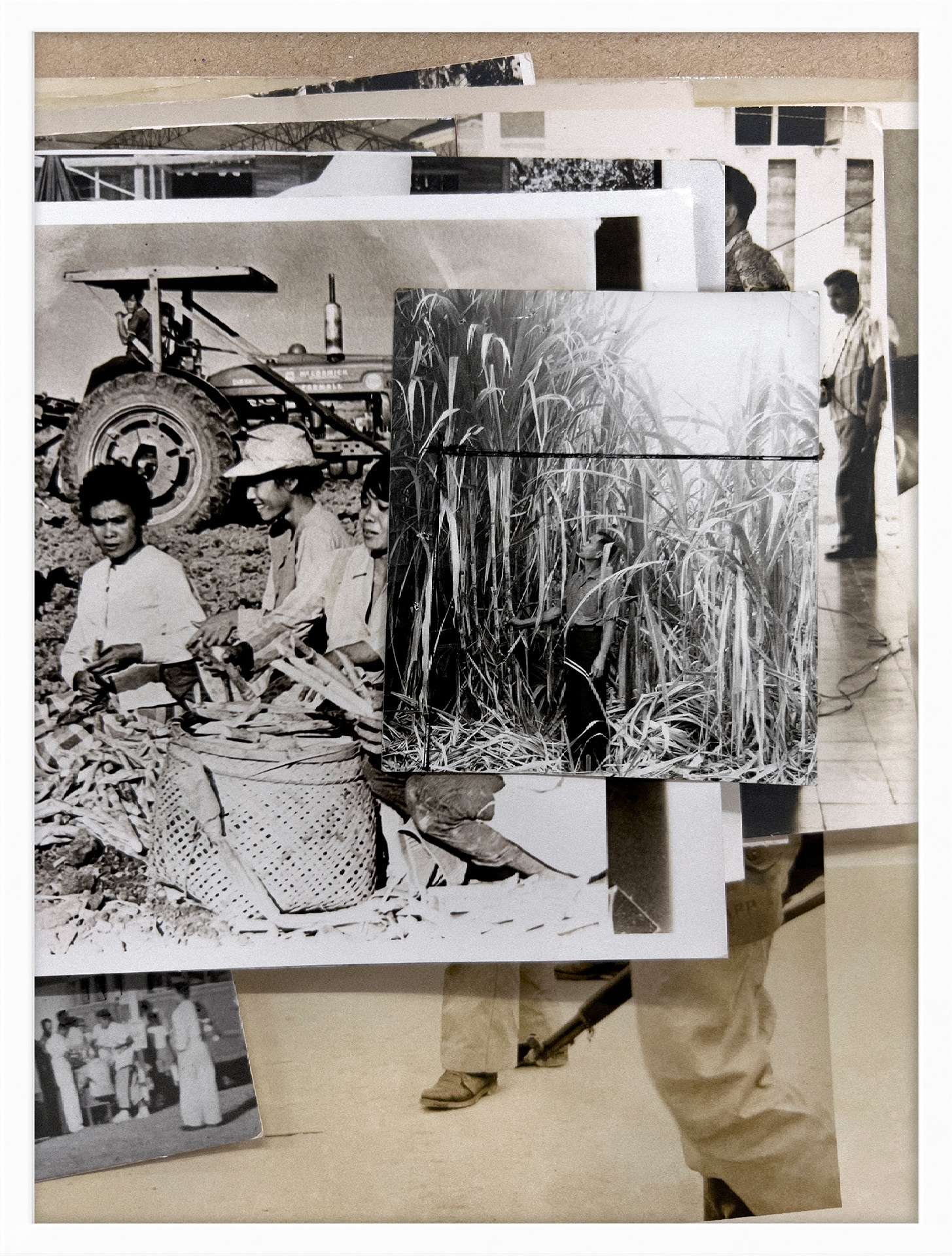

• Industry / sugarcane / abaca: as backdrop for post-colonial development and history. Exploitation of labor, creation of an export culture and wealth accumulation.

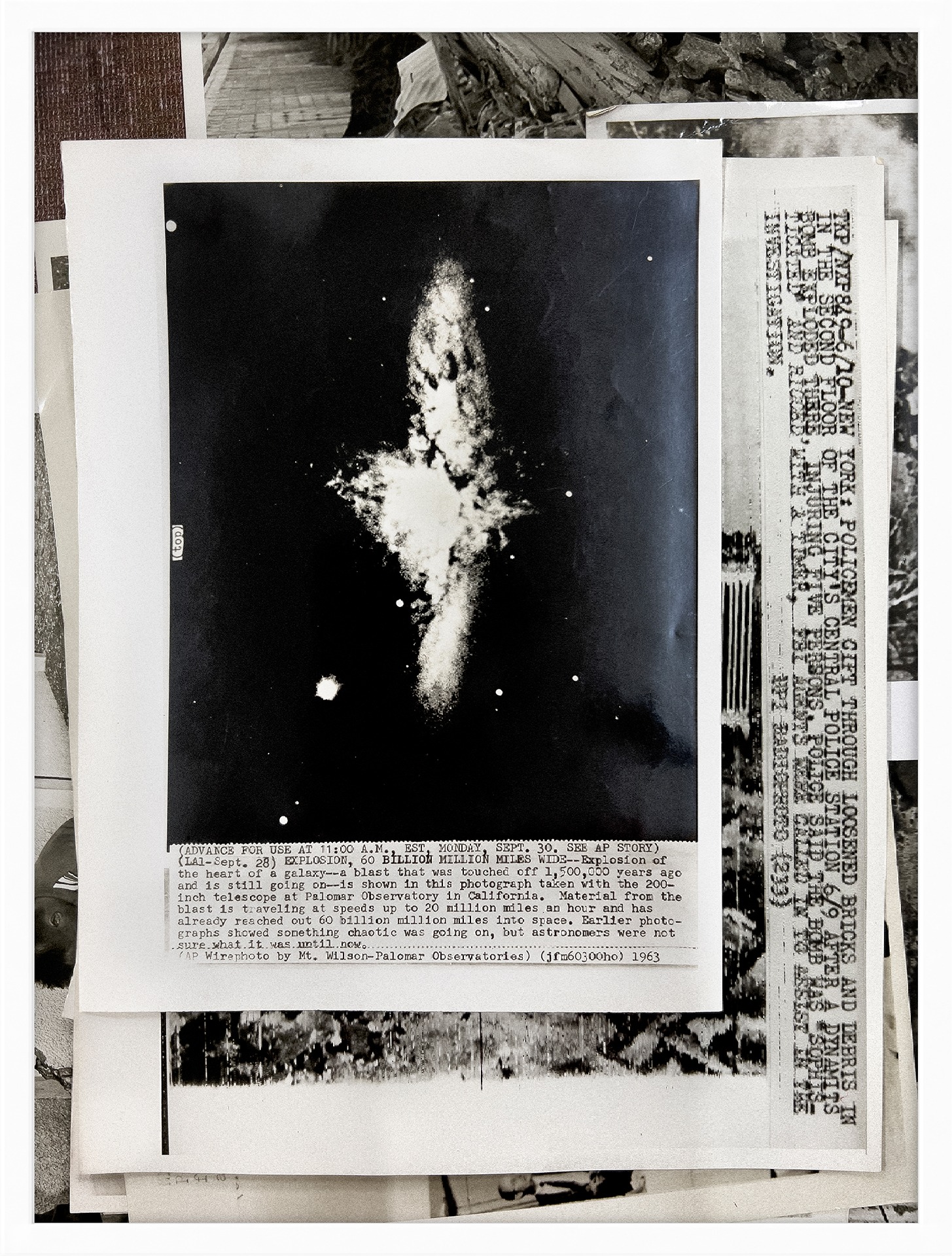

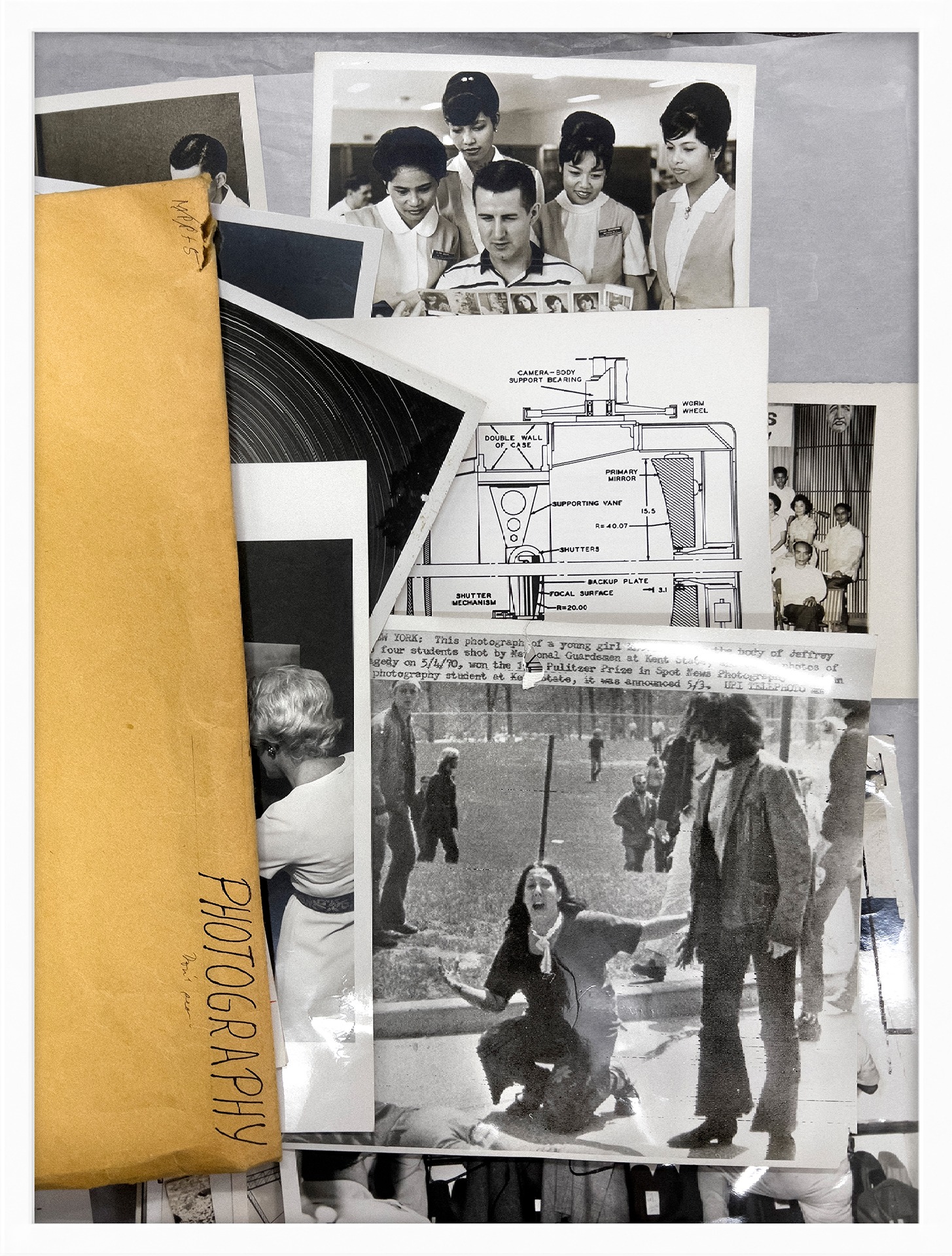

• The “West” -- small signs of the United States and its influence overlaid like a lingering headache (a white woman holding up a brunette wig with a look of disdain; a NASA galaxy press photo; a white man looking at images of Filipinas while other Filipinas look over his shoulder; Kent State photo

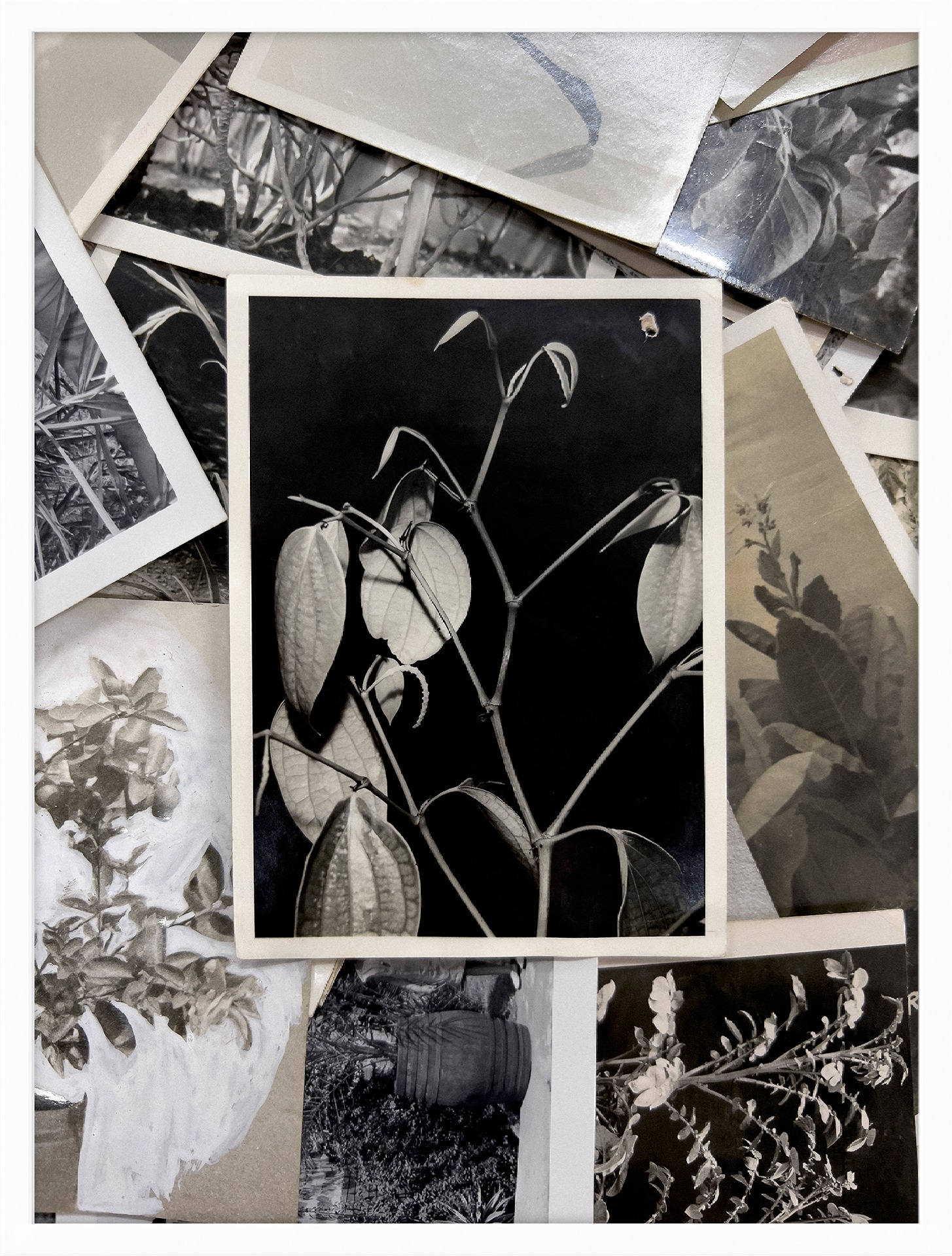

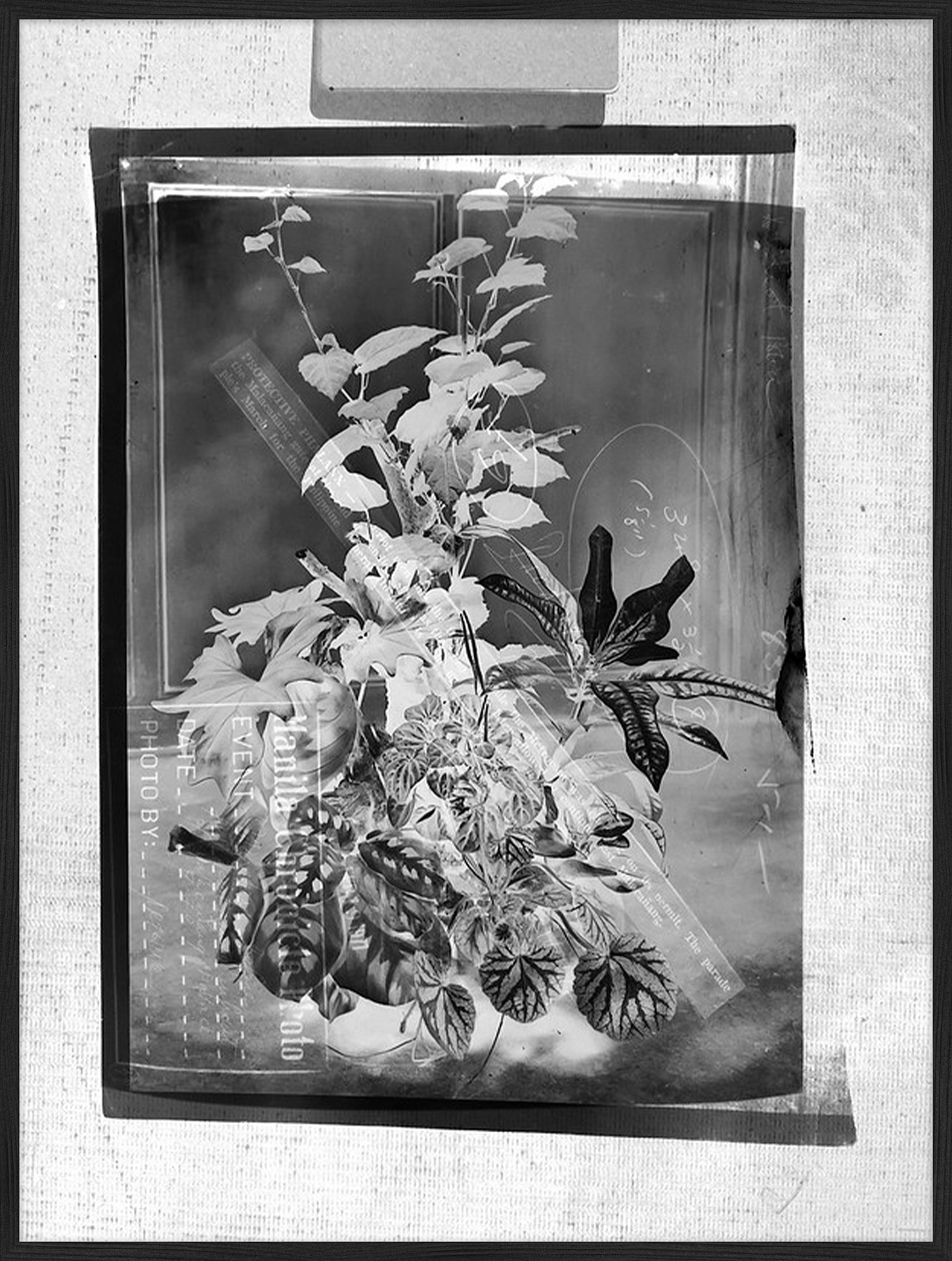

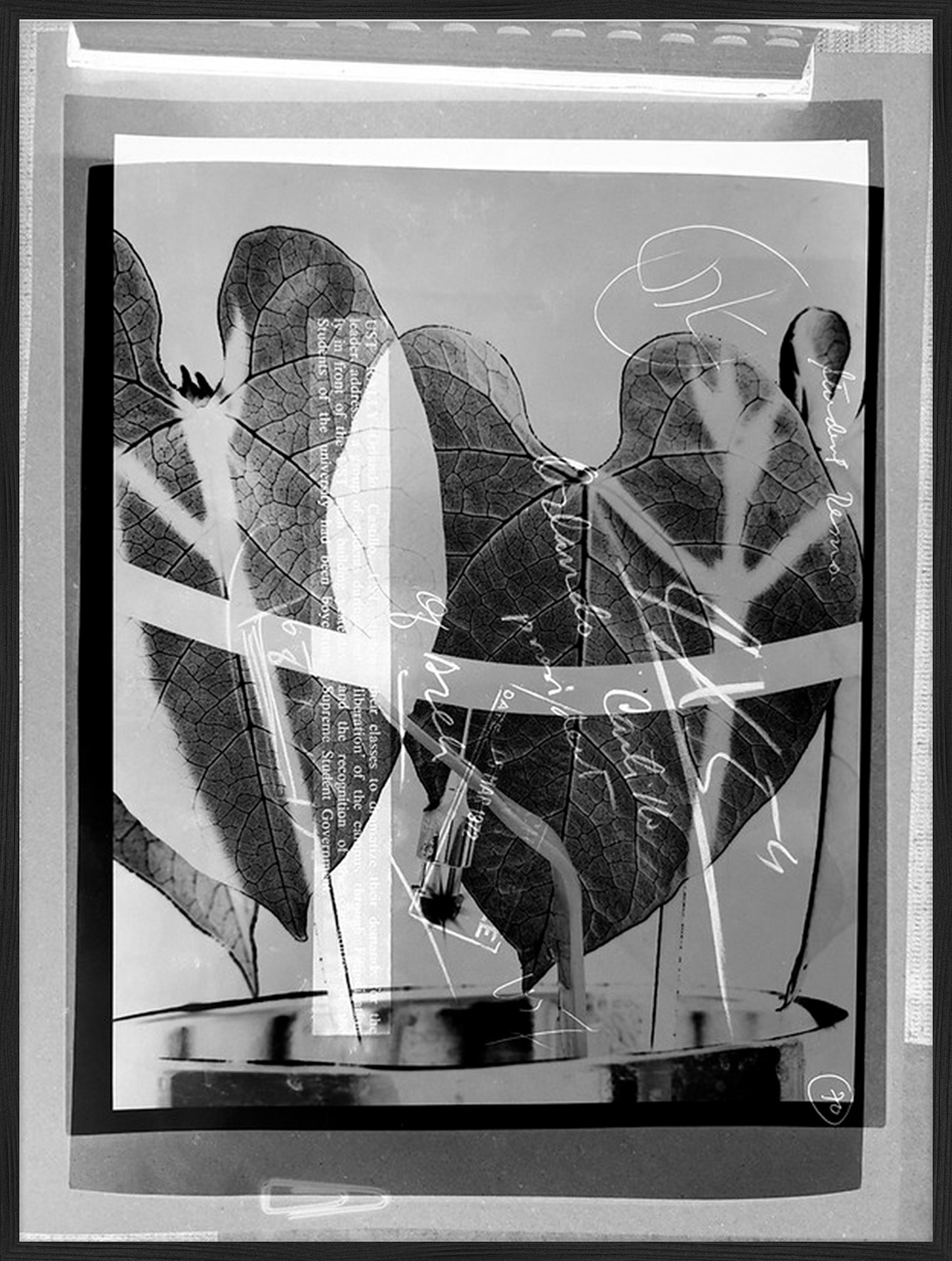

• “Decorator plants / tropical flora: cultivated landscape as manicured site. Metaphors of jungle and wilderness rendered symbolic, like a flower arrangement or still life.”.

The archival expedition into the LML material was pedagogic and personal, a balikbayan’s attempt to understand the nation that her mother left 50 years ago. It resulted in two related bodies of work, Force Majeure and Inherent Vice.

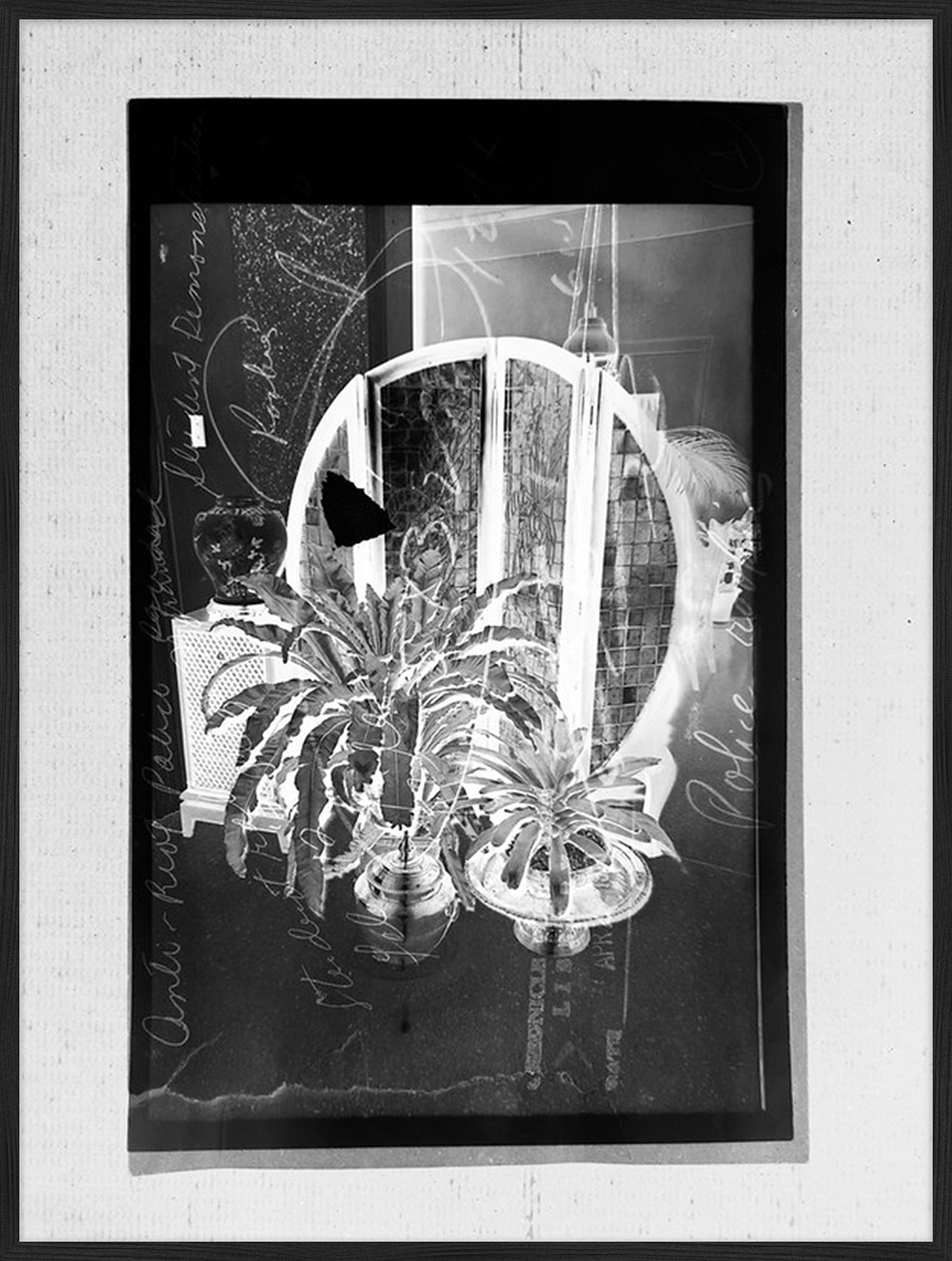

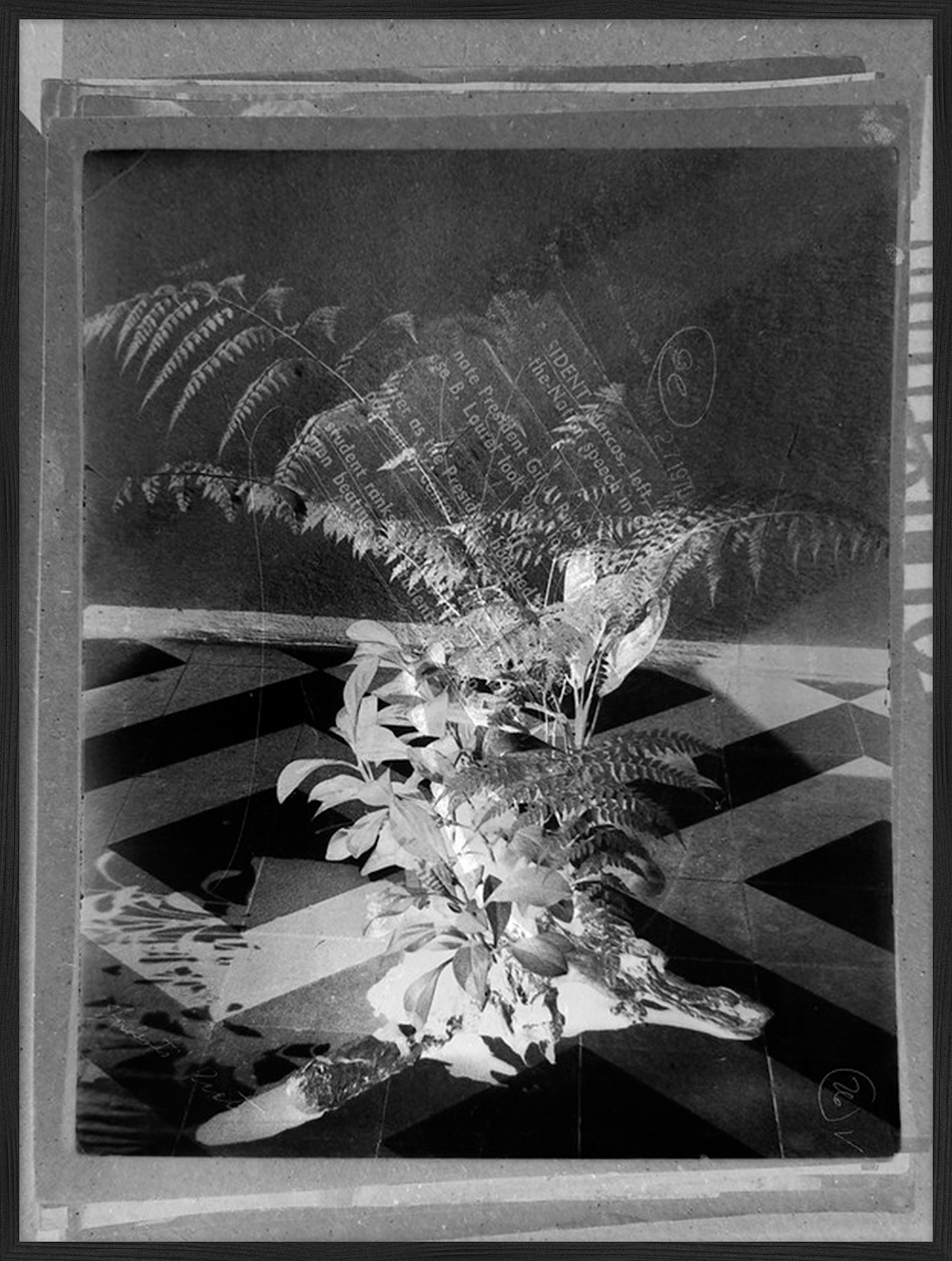

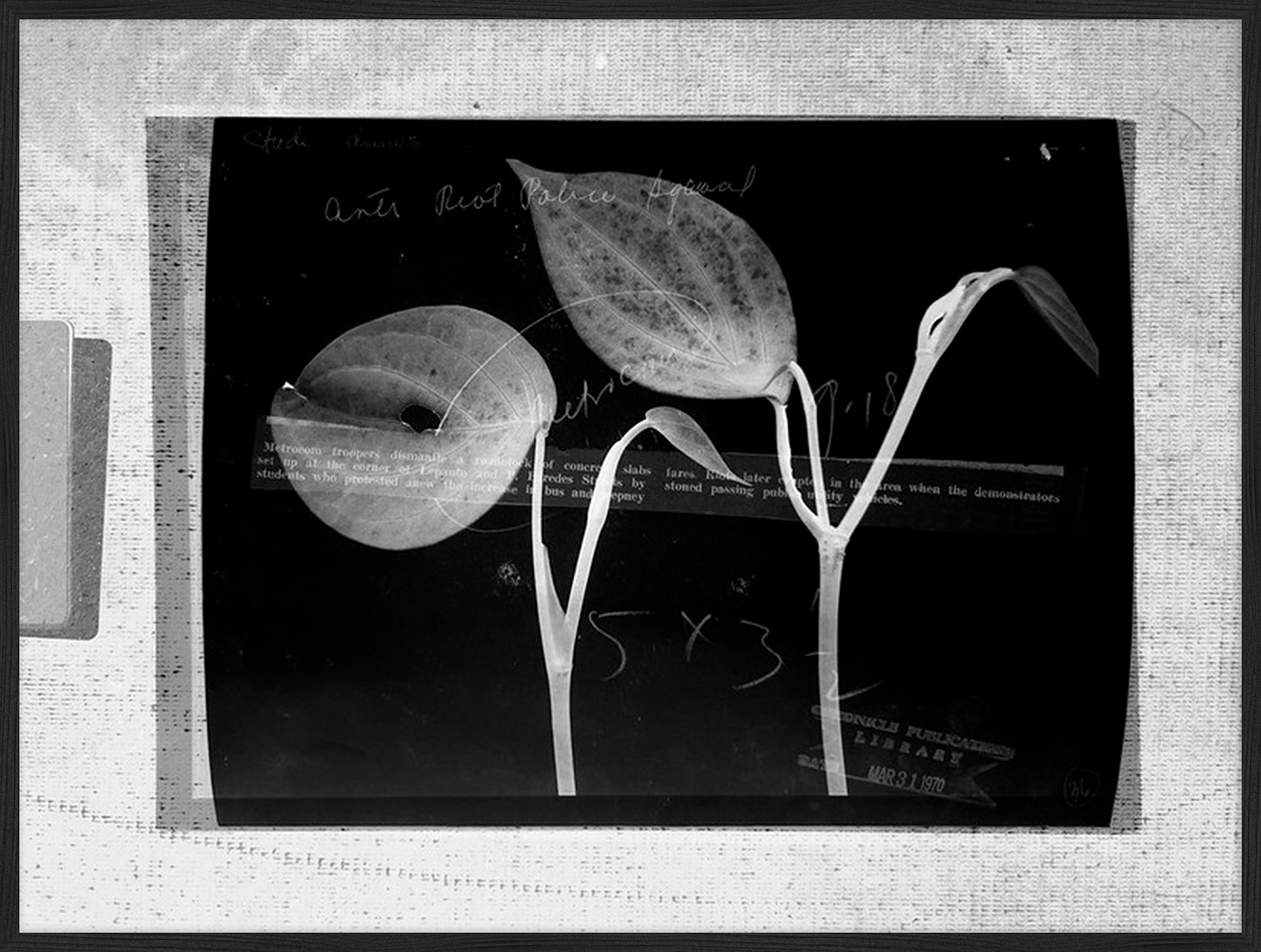

Force Majeure leans into the metaphor of tropical plants – isolated from the background, they recall colonial botanical illustrations – the beautiful and seemingly benign assertions of control and inventory of new imperial possessions. In Syjuco’s version they are overlaid with politically-charged news captions and presented as negative images simulating a forensic investigation. They share the wall with shadows of authority taming the unruly – a barber cutting the hair of a crying child, riot police confronting protesters, a president articulating his vision for a new society.

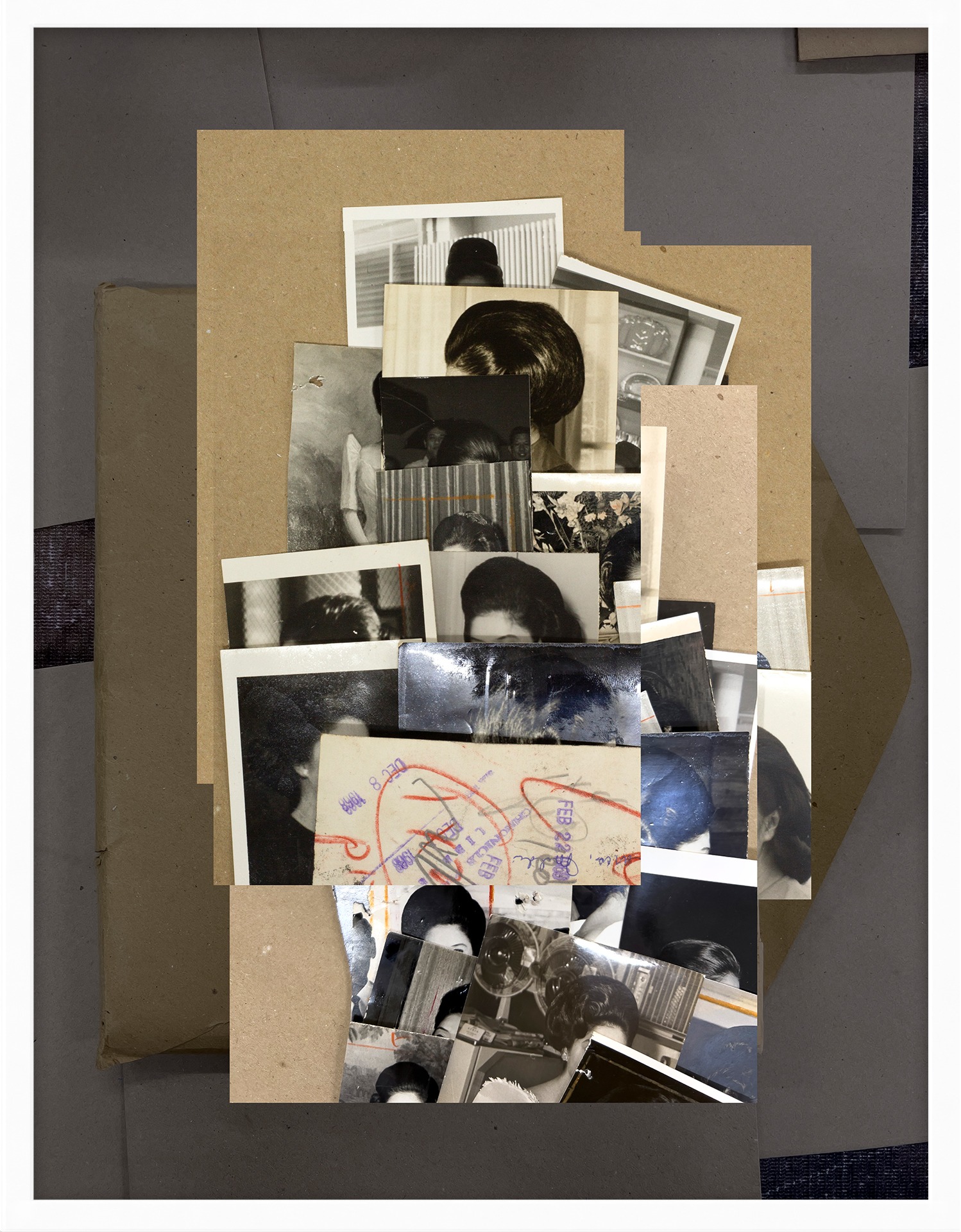

In the Inherent Vice series, she leaves the pictures unedited, reveling in their materiality, presented in thematic piles with editorial marks, handwritten labels, and portions of envelopes. The physicality is potent. They are the remains of a period when the image corresponded to something that was “real” and “actually happened.” We share in the visceral experience of handling photographs that were printed in a dark room and existed in physical form. We see evidence of material that – before her hands – passed through those of the journalists, editors, librarians, archivists, and researchers for over half a century.

In more than 20 frames and 900 archival pictures, the 60-minute video Inherent Vice (Deep Cuts) cycles through stacks of photos then zooms in on details, reinforcing the way that perspective informs each person's reception and remembrance of events in history. Meticulously compiled and categorized, the images reveal the pre-occupations, proclivities, and prejudices of that formative period.

The video work shares the room with a Lopez Museum and Library conservation set up in the smaller gallery, making visible inherent vice in its literal sense – the acidification that develops through impurities within certain papers – calling attention to the care needed by both the physical archive and the histories they carry.

It is impetus to consider how the very fabric of an object or society can contain the seeds of its own deterioration. We pause to reconsider how the tendencies of the 60s and 70s developed and mutated. Images of a nation trying to define itself reveal the patterns that have become woven into the fabric of our culture: opulence and artifice continue to entertain and obscure lingering social issues, security forces which were once the feared arm of the law have been co-opted and replaced by private security that maintains social order in public spaces, our fondness for protagonists and antagonists distracts us from the systems that enable them.

At the inauguration of the Lopez Museum and Library, then called the Lopez Memorial Museum, in 1960, Claro M. Recto articulated the institution’s reason for being: to offer a sense of historical continuity. At that point in time, there was hope that a sense of shared history among the youth would engender a sense of shared destiny. The work of Stephanie Syjuco aids us in our critical examination of history. She challenges neat presentations of oft repeated themes that have become seared into our collective memory to form a linear narrative, Syjuco’s collages and layered visual composites acknowledge the fragmented way in which we remember history.

– Yael Buencamino Borromeo

¹During the period between the Japanese Occupation and the Declaration of Martial Law, the Philippine press was believed to be the freest in Asia. This assertion though is complicated by the fact that most periodicals were owned by the same families that owned big businesses.

“Media enterprises, being dependent on busi- ness and political subsidies, practiced self-censorship and filtering of information that is perceived to be detrimental to benefactors. (Communication Media in the Philippines: 1521-1986, Florangel Rosario-Braid and Ramon R. Tuazon)

Notwithstanding these conflicts of interest, photojournalism flourished, especially in the 1960s and 70s. Space was given for photo essays with creatives that are now National Artists serving as editors, layout artists and illustrators. In 2007 Silverlens Foundation exhibited “ 5 photographers : a tribute to 5 pioneering masters of Philippine photojournalism”: Joe Gabor, Romy Vitug, Mario Co, Silverio Enriquez, and Ed Santiago. All five photographers worked for the Manila Chronicle. It is likely that their images are among those selected by Syjuco but given the absence of attribution in the photo morgue, we are unable to ascertain who took which photos.

Stephanie Syjuco (b. 1974, Manila, Philippines; lives and works in Oakland, California) is known for her investigative, research-based practice encompassing photography, sculpture, and installation. Progressing from handmade and craft-inspired mediums to digital editing and archive excavations, her work employs open-source systems, shareware logic, and capital flows to scrutinize issues related to economies and empire. Initially exploring image-based processes and their implications in constructing racialized, exclusionary narratives of American history and citizenship, she has shifted her focus to the history-building and myth-making undertaken by Filipinos in their newfound independence. From critiquing images of American colonial anthropology in the Philippines, to investigating historical museum collections and shuttered newspaper archives, her projects attempt to reframe and “talk back” to the archive.

Syjuco received her MFA from Stanford University and BFA from the San Francisco Art Institute. She is the recipient of numerous awards, including a 2014 Guggenheim Fellowship Award, a 2020 Tiffany Foundation Award, and a 2009 Joan Mitchell Painters and Sculptors Award. She was a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellow at the National Museum of American History in Washington DC in 2019-20 and is featured in the acclaimed PBS documentary series Art21: Art in the Twenty-First Century. Her work has been exhibited widely, including at The Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Whitney Museum of American Art, The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, The Smithsonian American Art Museum, The Getty Museum, The Walker Art Center, and The 2015 Asian Art Biennial (Taiwan), among others. A long-time educator, she is an Associate Professor in Sculpture at the University of California, Berkeley.

Installation Views

Works