"Together the works examine themes of family, narration, diaspora, repair, and remediation in art."

"The trope or grand cliche in art, of the breakdown of material by hand or machine, is what imparts uniqueness and difference in the work."

- Jill Paz

Like so many people today Jill Paz is both and between. Born in the Philippines but leaving as a one year old for Canada, educated there and in the USA, married to a US citizen, she returned to the Philippines four years ago. The works by which she as an artist became known took both as material and imagery that emblem of the Filipino diaspore or migration, the balikbayan box, and the paintings of the renowned Filipino painter Félix Resurrecíon Hidalgo, her great grand uncle.

To use such subject matter was a way of musing on her own situation: in some ways perhaps both Canadian and Filipino, but also perhaps between these different identities.

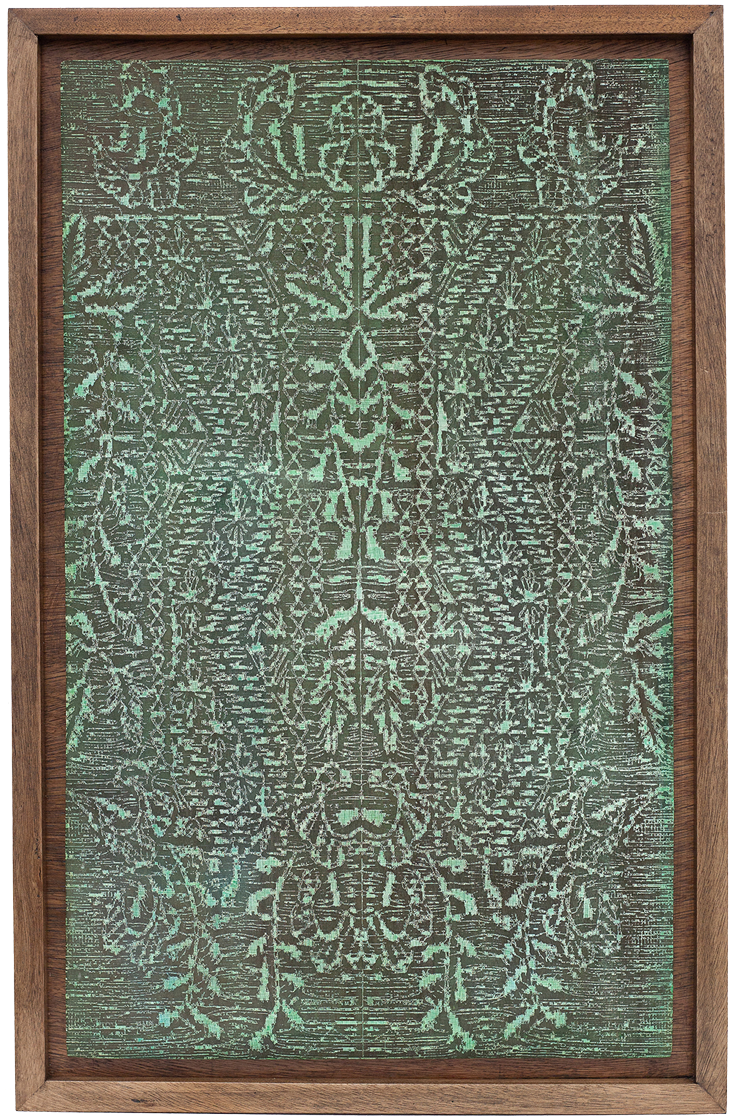

Living Room, 2021

acrylic on laser-carved wood in artist’s frame (detail)

It may not be immediately apparent how her new body of work shows the same pre-occupations, the same sense of displacement. The differences are obvious: there is no sign of a balikbayan box; in only two of the twenty paintings does she return to images of the painting filled rooms of the Hidalgo ancestral house.

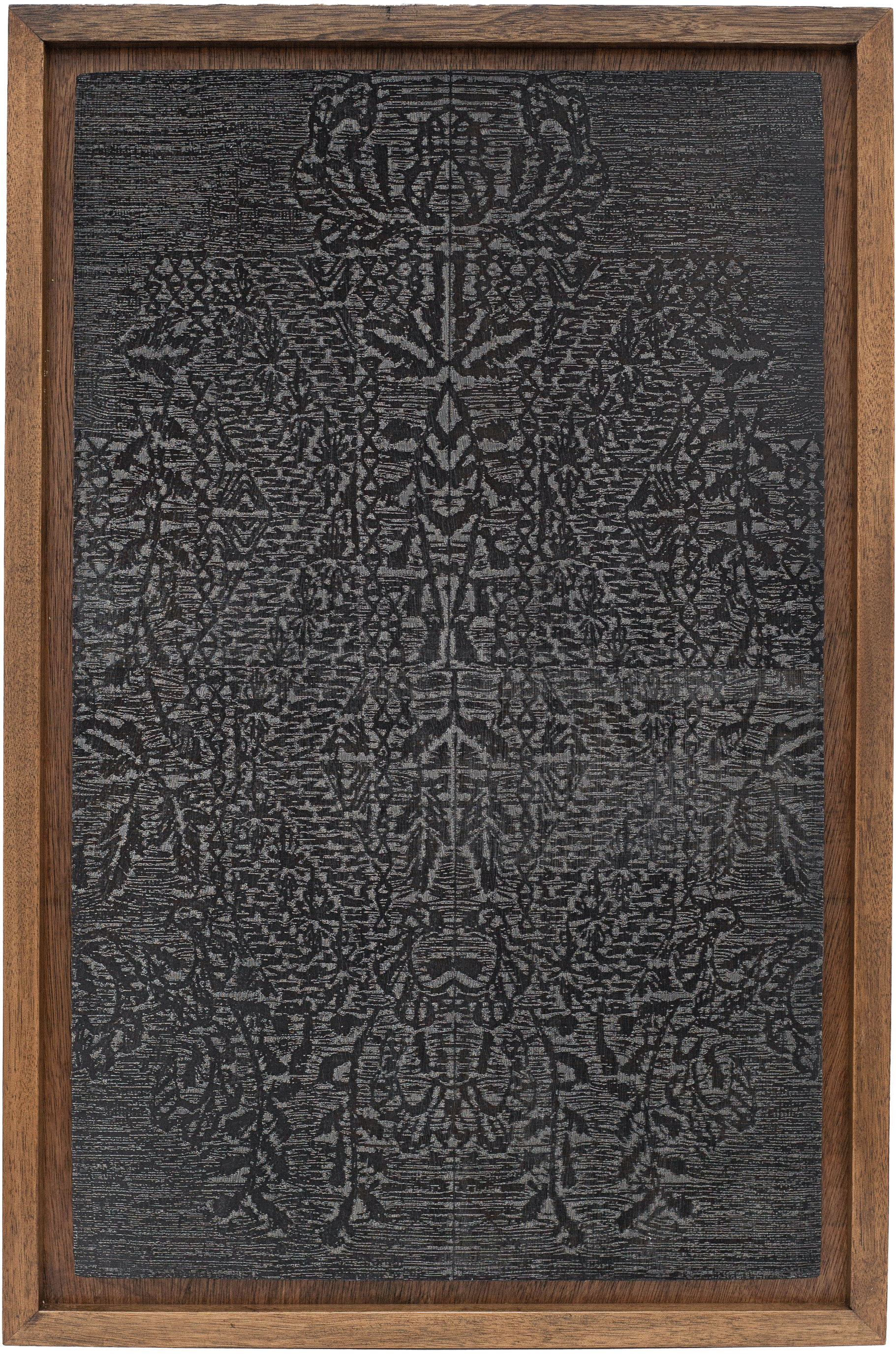

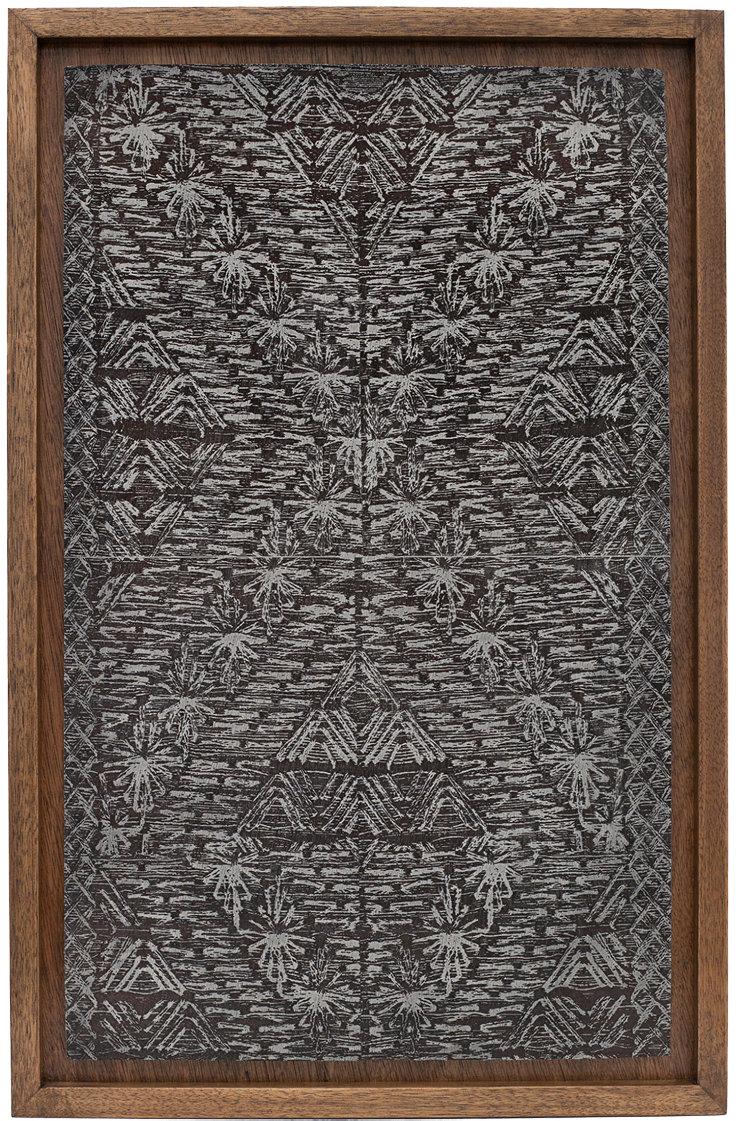

(L-R) Untitled (Black Painting Vertical), Untitled (Embroidery Black), and Untitled (Green Painting Vertical), 2021

acrylic on laser-carved wood in artist’s frame

She calls these paintings “abstract”. Technically speaking, they are not abstract, but are instead abstracted from actual images or surfaces. They do not aspire to the purity, grandeur and high ideals of abstract painters such as Kandinsky or Barnett Newman. Her works always refer to things of this material world: small, fragile, damaged and repaired objects, or fabrics.

Also, she calls these paintings “domestic”. Moreover, she has referred to them as “intimate”. We could go further and call them homely, or kitchen paintings. They are of this time: in the lockdown the restaurants and fast-food joints disappear and the kitchen table becomes the centre of many people’s universe. We become very aware of what Norman Bryson in his influential book Looking at the Overlooked: Four Essays on Still Life Painting (1990) calls feminine space.

Vase Painting, 2021

acrylic on laser-carved wood in artist’s frame (detail)

Vase Painting, 2021

acrylic on laser-carved wood in artist’s frame (detail)

How does this intimacy reveal itself? Her working process, using a laser to burn a digital image on to a surface, seems analytical, impersonal, unemotional. Her subsequent application of paint leaves no trace of gesture, shows no personal “handwriting”. She has talked of making these works with the “cool air of detachment evident in the self-effacing processes of Minimalism.” But yet the paintings seem plaintive to the sensitive viewer.

Talking of his monochrome paintings, the American painter Brice Marden once explained to me that despite the rigour with which they were made the mistakes or imperfections that slipped in were crucial. Paz says something similar: “I allow for imperfections to creep into an otherwise precise technology of reproduction.” In the process approximations, mistakes, unexpected nuances occur. The skill of the artist is in allowing and managing such accidents, such nuances.

Still Life Drawing, 2021

acrylic on laser-carved wood in artist’s frame (detail)

Still Life Drawing, 2021

acrylic on laser-carved wood in artist’s frame (detail)

In so doing a sensibility seems to slowly appear. Like leaves rustling in the wind, or the murmuring of the ocean. We could say that she allows the world to breath or whisper.

Tellingly, in a recent interview she talks of the kinship she feels for artists such as Agnes Martin or Doris Salcedo. Subtle artists, where sensibility - and beauty - is revealed through an apparently austere method and a limited choice of materials. Paz belongs that tradition of the understated, the intimate, where the effect depends on the accumulation of small nuances, not grand bravura gestures. One could see Vermeer or Mondrian as being in that tradition, but also many, lesser-known female artists such as Orsola Maddalena Caccia or Louise Moillon, whose works speak of attention and humility, or the Jansenist influenced Philippe de Champaigne and Lubin Bauguin. It is a tradition or undercurrent that also runs through photography, from the early practitioners like Anna Atkins with her delicate photograms and Édouard Baldus with his salt prints and paper negatives to contemporaries such as Dirk Braekman or Craigie Horsfield.

Their affect depends on attentiveness, not shouting, on empathy, not egotism. They are not trying to impress the viewer: they are calling for empathy. Indeed, their work is about empathy, about belonging in the world,

The subjects of these new paintings by Paz are small, damaged and repaired objects: things you can hold in your hand, albeit seen as if darkly through digitalisation. Or fabrics, dematerialised by the scanner then reconstituted in gesso.

This is an archaeology of everyday life. This is a discourse on the humility and complexity of small things and tender surfaces.

Figure 3, 2021

acrylic on laser-carved wood in artist’s frame (detail)

Writing in the dying days of August 2021 I see endless images of refugees from Afghanistan, waiting for planes or arriving at airports far away, staring at a new, unfamiliar world. They own nothing now but the clothes they wear and perhaps a bundle of extra clothing. Fabrics are intimate, they still smell of their lost home.

Though our sufferings and the danger we face are so little compared to those attempting to flee Afghanistan, the pandemic has made us all a little like refugees, wary of the public spaces, huddled in the comfort of the kitchen, our hands clutching some familiar object, or more probably, some familiar piece of cloth or clothing. In an age of migration, textiles become our only certain home.

-Tony Godfrey

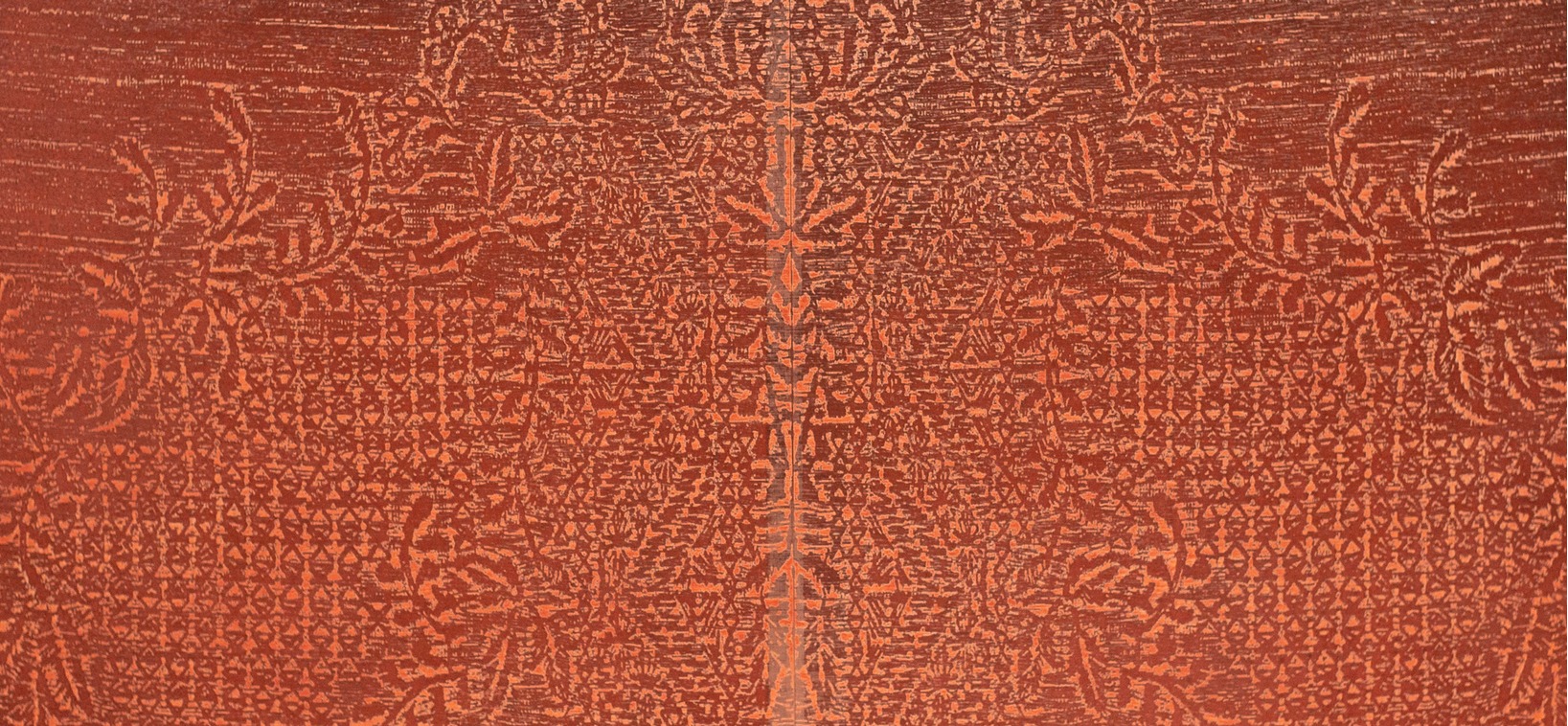

Untitled (Red Painting Horizontal), 2021

acrylic on laser-carved wood in artist’s frame (detail)

"By exploring remediation in art and the transference of objects in our cultural systems, the process questions the meaning of these objects as they circulate through cultural systems in an era defined by an over stimulation of images."

- Jill Paz

Video

About

Recently I have been exploring the abstractions, repetitions, and systems of our everyday lives that often get neglected. My domestic life has been magnified in the midst of this pandemic; and though I am not seeking an overtly personal project, my starting point is the pre- existing composition of my ancestral home. From there, I am extracting something new from identifiable objects, as well as textile grid patterns that are deeply rooted in the history of Modernism and Abstraction. By exploring formalist tensions and the breakdown of material, I continue to ask myself: what is the meaning of repair and preservation? And what does it mean to craft a visual vocabulary that speaks of formal elements such as repetition and the slow time of domesticity?

The new body of work titled Domestic Abstractions consists of 20 intimately scaled panel paintings. Each painting has an intricately detailed surface, made by the digital optical tool of a laser machine and then layered with acrylic washes on top of a gesso ground. This rigorous consistency of the framework appears to be a conceptual process, but within these systematic conditions opens up the possibilities of exploring a pictorial world.

My old home in New Manila

In Domestic Abstractions, I continue my ongoing investigation of how objects fall apart, its subsequent need for repair, and how these structures of preservation connect to values of interdependence and interconnectedness. The formal and conceptual start of this project began with a desire to excavate the uncanny history of our family home of my mother's lineage. Still standing on a corner of Broadway in the old neighborhood of New Manila, my grandfather’s century old home being a family home for 4 generations, was a radio headquarters during the Second World War. The home’s foundational structure was altered to include a bunker and tunnel during those years of Japanese occupation. Subsequently after the war, the American army took over the home, leaving my grandfather displaced from his home for another couple years. Since 1950, the home has undergone an endless series of renovation projects as the burgundy roof weighs down on the walls in a comical way, it looks tired of its own weight, the teal colored walls of the living and dining rooms have seen better days, and yet from the dim light of the vintage chandeliers, nostalgic with a warm cozy 1950’s kind of charm. A few charcoal on paper sketches by the Philippine painter Felix Resurrection Hidalgo, adorn the walls. The poses of the charon from Hidalgo’s iconic painting La Barca de Aqueronte hauntingly invite one to the spiral staircase that lead down to the basement, where behind the bookshelves lie a forgotten tunnel left behind after the war.

On my last visit to my grandfather’s home a couple months ago, a construction team was busy hammering on the roof, keeping it from falling into itself in the midst of the pandemic. Despite decades long renovation projects, the tropical heat, giant towering mango trees that sway dangerously close to the gables, and Manila’s growing urban sprawl, have different plans. The home truly is ever decaying and ever re-greening like Manila itself. I suppose no home is built for posterity any more, and everything is susceptible to time and change.

In the green tinted panel painting titled Living Room, I have taken an old photograph of our home’s interior space from my personal archive. Using Photoshop editing techniques and a computer program designed for the laser machine, I recreated the image with a ben day dot filter, a pattern that makes a half-tone image reproducible. I am not as interested in the invention of a new composition, but rather extracting something new from a found object or photograph. The use of photography in my painting process reaffirms the cool air of detachment evident in the self-effacing processes of Minimalism. In Still Life Drawing, which began as a charcoal rendering, and then further distanced and abstracted to a ben day dot pattern, there is left no trace of the drawing except for its title. Despite all the works’ hand-painted final treatment, there is no gesture of the brushstroke.

A Systematic Approach of a Pictorial World

The conceptual process of the paintings is a systematic approach of a pictorial world. It begins with hand drawn sketches and photography, followed by editing tools on the computer, and a simultaneous controlled carving on the wood panel using the optical lens of a laser machine. Lastly I hand paint thin washes of acrylic paint on the panel’s detailed surface.

The mark making that I control with the laser machine, a device that can translate a digital image into a rasterized or burnt etching on a wide variety of materials, is unlike a reproduction. The printed mark here is qualified by a painterly gesture. The visual tension on the panel’s surface is embraced as I allow for imperfections to creep into an otherwise precise technology of reproduction. The trope or grand cliche in art, of the breakdown of material by hand or machine, is what imparts uniqueness and difference in the work. Looking at the degree of abstraction that the process imparts is a formal template that I work with and then manipulate to allow for glitches and slippages to happen.

The works also stem from my fascination with how images traverse our visual and material culture. Remediation in art is the act of transferring affects of one medium onto another. I am taking objects and images from my personal archive and passing them through a series of material transformations. By exploring remediation in art and the transference of objects in our cultural systems, the process questions the meaning of these objects as they circulate through cultural systems in an era defined by an over stimulation of images.

The rigid logic is echoed in the panels’ structure, which follows a longstanding art historical use of the golden ratio to craft the compositions. The golden ratio is a rectangle where the ratio of the longer side to the shorter side is exactly the same as that of the sum of these two to the longer side.

Aside from the subject matter made from drawings and personal photographs of my family home, a portion of the panels have a symmetrical pattern carved onto its surface, which are derived from piña fabric embroideries. All panels are measured in a golden ratio, except for 2 square paintings hung diagonally. Titled Red Painting, the monochromatic panel is derived from a detailed photograph of a piña fabric embroidery, that is further manipulated on computer programs and made into a symmetrical bitmap file. The optical pattern appears flat, and differs from the interior images and still lifes. I was drawn to the optical pattern of these weavings, its colonial and native history, and also the aspect of weaving as inherently women’s work. The process of the weaving textile is similar to the rhythm of the laser machine, in that it follows an x and y axis. Marks are either horizontal or vertical bands made through the laser machine process, which is essentially burning portions of the substrate, and the repetitious positive and negative mark making is further emphasized by the tint of acrylic washes. The visual tension on the panel substrate is that of shadow and depth while the rhythm of the work is of quick staccato-like marks.

Despite these rules, there are elements of arbitrariness and chance. The fabric itself is slightly stretched prior to photographing it in detail, while the figure and still life, both vintage porcelain and ceramic objects, have been broken from age. In an act of repair, I am putting it back together and re-creating the textiles pattern and objects on the computer, before finalizing the composition on panel.

By exploring tactile manipulations of analog and digital tools, there is a breakdown of substrate by the machine. In the painting titled Figure Drawing 4, there is a breakdown of that surface that occurred from the optical lens burning the surface of the panel substrate. Despite the rigorous consistencies, there is fragility and vulnerability of materials and processes. In coming to grips with the degree of abstraction that the material world imparts, I am exposing the layered complexities of art objects in order to renovate and repair my understanding of place and of home.

Together the works examine themes of family, narration, diaspora, repair, and remediation in art. My personal narrative is a driving force in my process, while my explorations on repair is a way for me to look at my past so as to identify my relationship with the present.

As I spend more time at home, I am looking more at the backdrop of my everyday life and taking this material to use as indexes for a pattern. The way for me to tackle such an overtly personal project of the family home as a starting point, was to respond to the fragmented details and reconsider its structures, shapes, and textures, all within the context of Formalism. The convoluted process was a series of repeated attempts, as ideas and compositions were pushed to abstraction, opened up and reconfigured into something unique. In favor of re-defying the idea of painting, I fully embrace the potentiality for art in chance ruptures. The potential for art is in those fallible attempts.

Filipino-Canadian Jill Paz (b. 1982) emigrated to North America in the early eighties and in 2017, returned to Manila where she now lives and works. As such Paz is informed by her experience as an immigrant, and her artworks are suffused with the lyrical tone of diasporic intimacy. Her emphatically process-oriented approach to painting combines analog and digital techniques to create intricate approximations that explore themes of repair and preservation. Recent solo and group exhibitions include Alliance Française Manille, Makati (2020); Centre Intermondes, La Rochelle (2019); Unttld Contemporary, Vienna Contemporary, Vienna (2019); Danubiana Meulensteen Art Museum, Bratislava (2019); and Art Basel Hong Kong (2019). Paz graduated with a MFA and BFA at the Columbus College of Art and Design; and studied Art History at the University of British Columbia, and attended a studio program at Parsons The New School for Design, New York. Paz has attended artist residencies at Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, Banff, Centre Intermondes, La Rochelle, and Mildred’s Lane, Narrowsburg, New York. She was the recipient of the 2016 Visual Arts Fellowship for the Columbus Museum of Art and Saxony State Ministry and subsequently attended a residency at GEH8, Dresden Germany. Paz’s works are in the collection of Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, and private collections internationally.

Professor Tony Godfrey has been writing and lecturing about contemporary art since 1978. He left London for Singapore in 2009 and now lives in the Philippines. His most recent book, The story of Contemporary Art (2020) is published by Thames and Hudson and MIT. His next project is a website of interviews with Filipino artists (Jill Paz being among the first six to be published).

Works