Raised by Mountains

John Frank Sabado & Leonardo Aguinaldo

Silverlens, Manila

About

Being raised in the mountains means always seeing the world at an altitude. The expansive becomes intuitive, and the interconnected is reliable. This is examined in John Frank Sabado’s portraits of people who have shaped his sense of communality from childhood. In Leonardo Aguinaldo’s works, the figures see themselves as seeing the world change and how they wish to be seen in it.

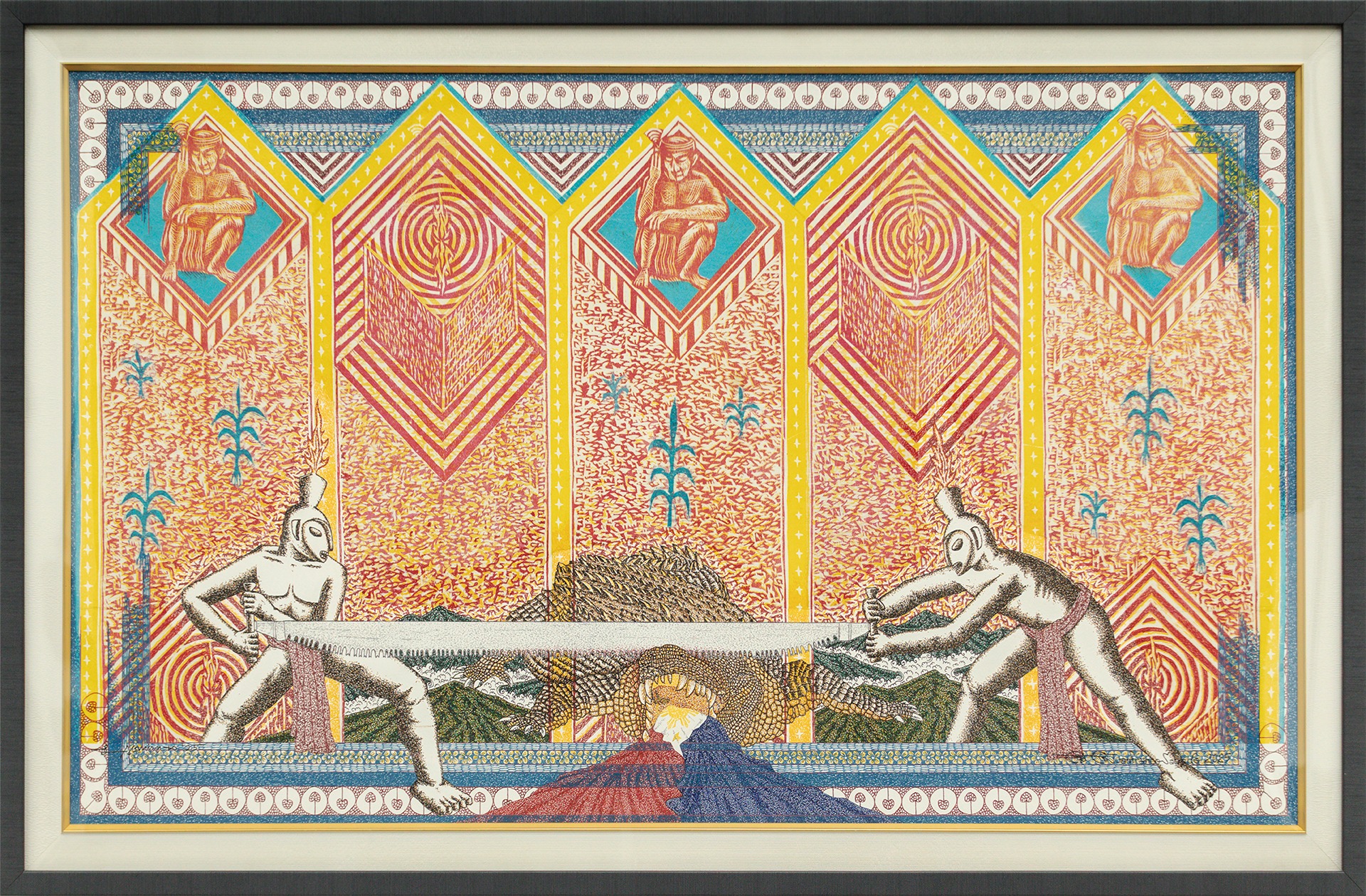

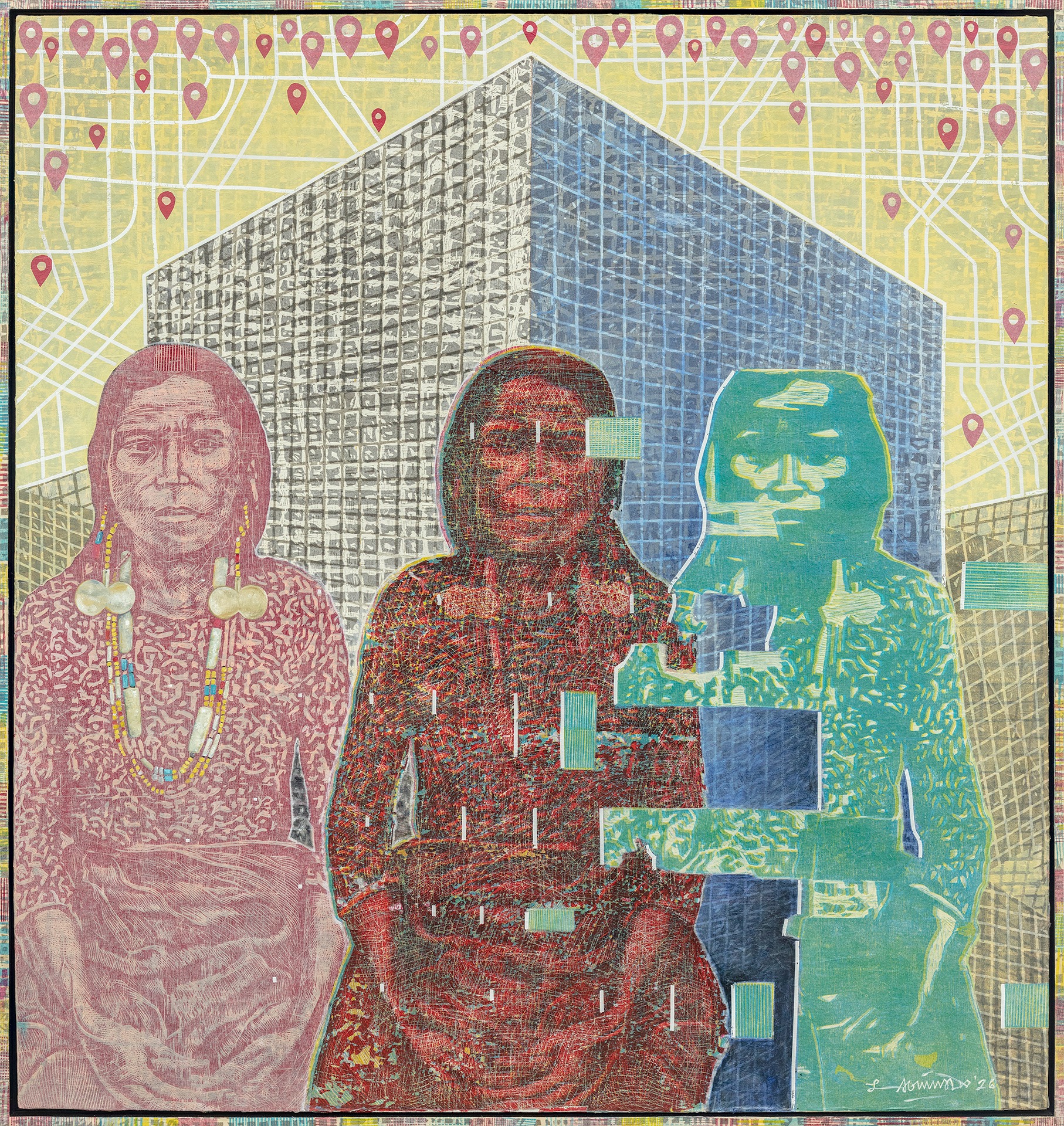

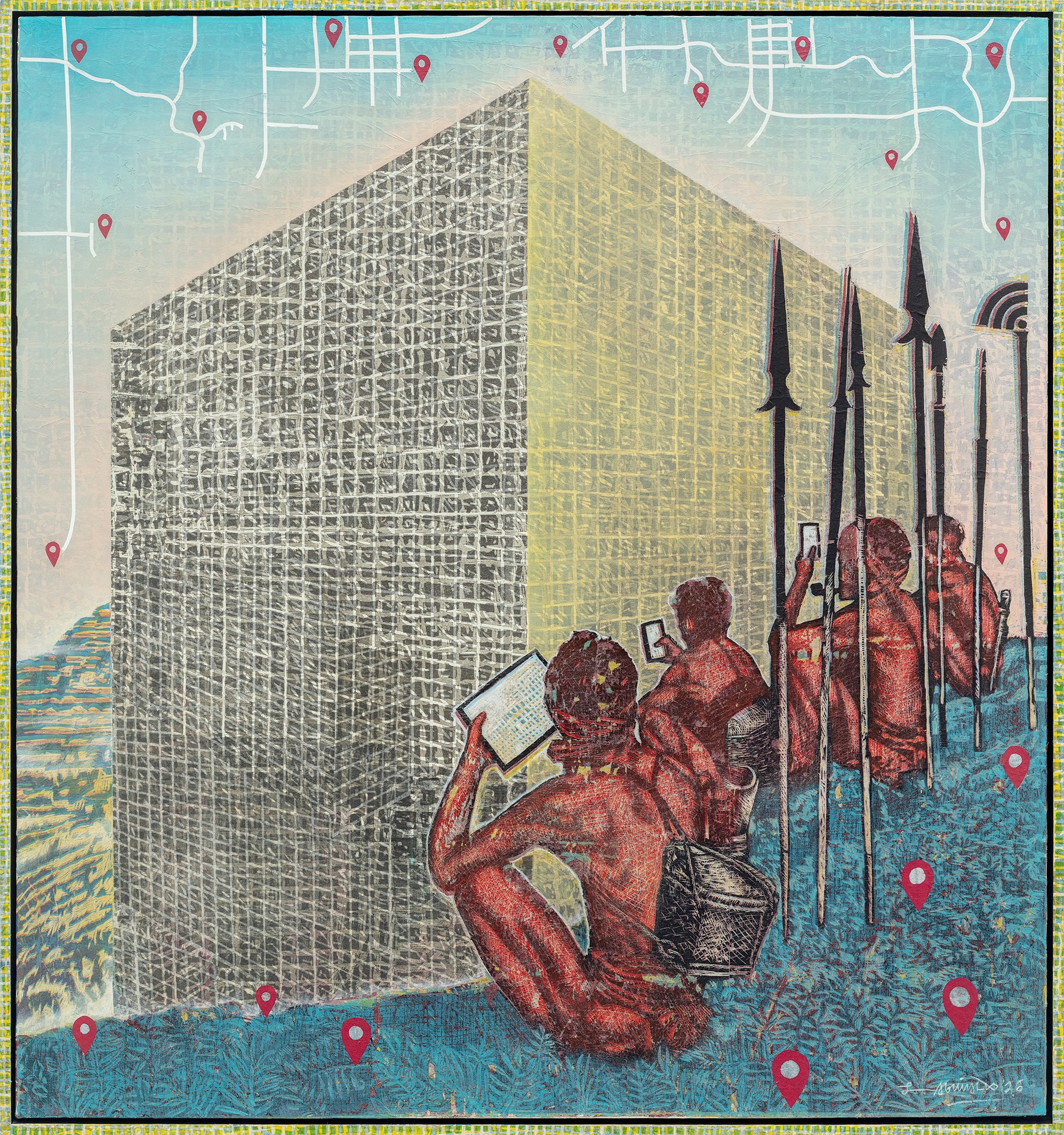

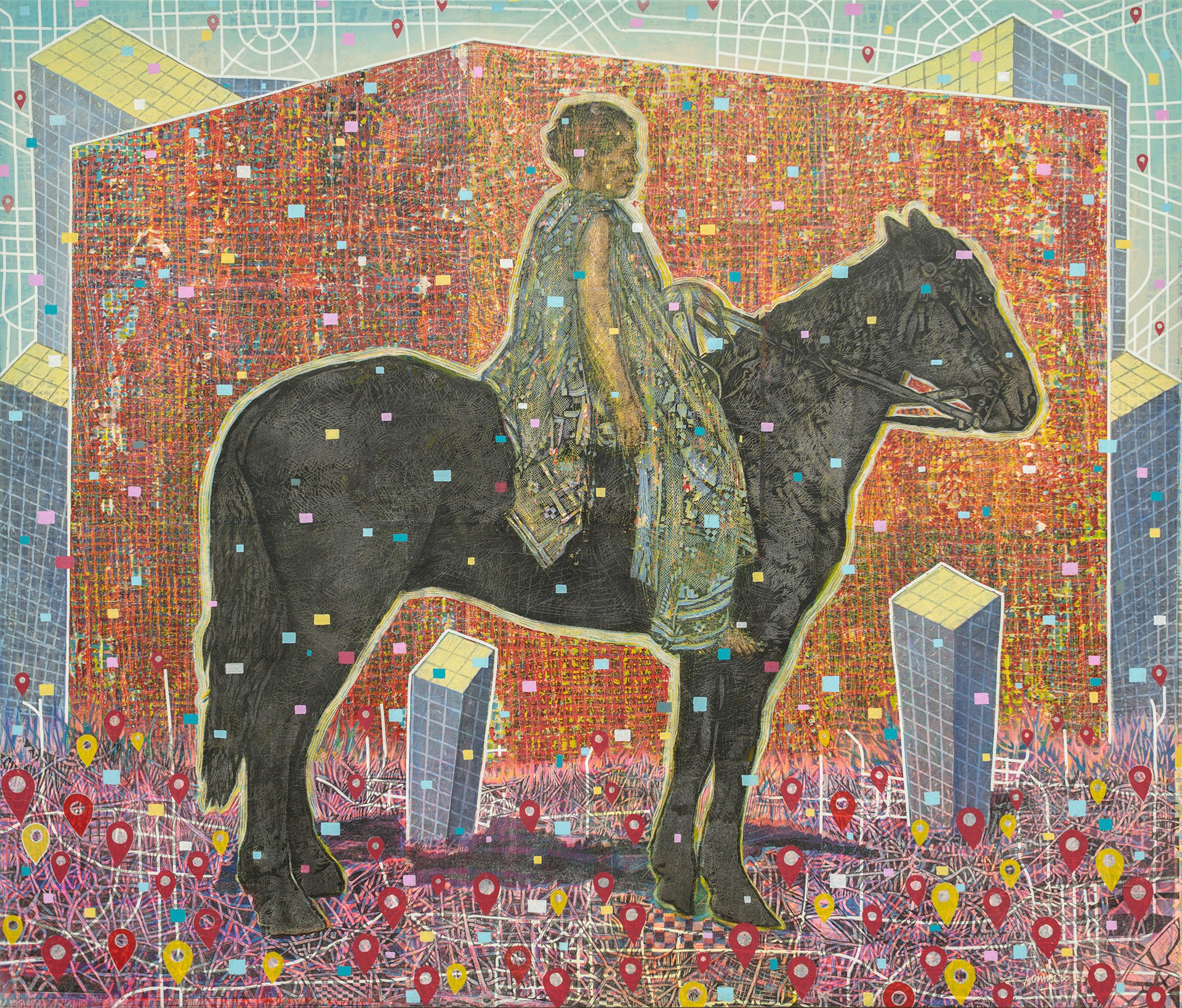

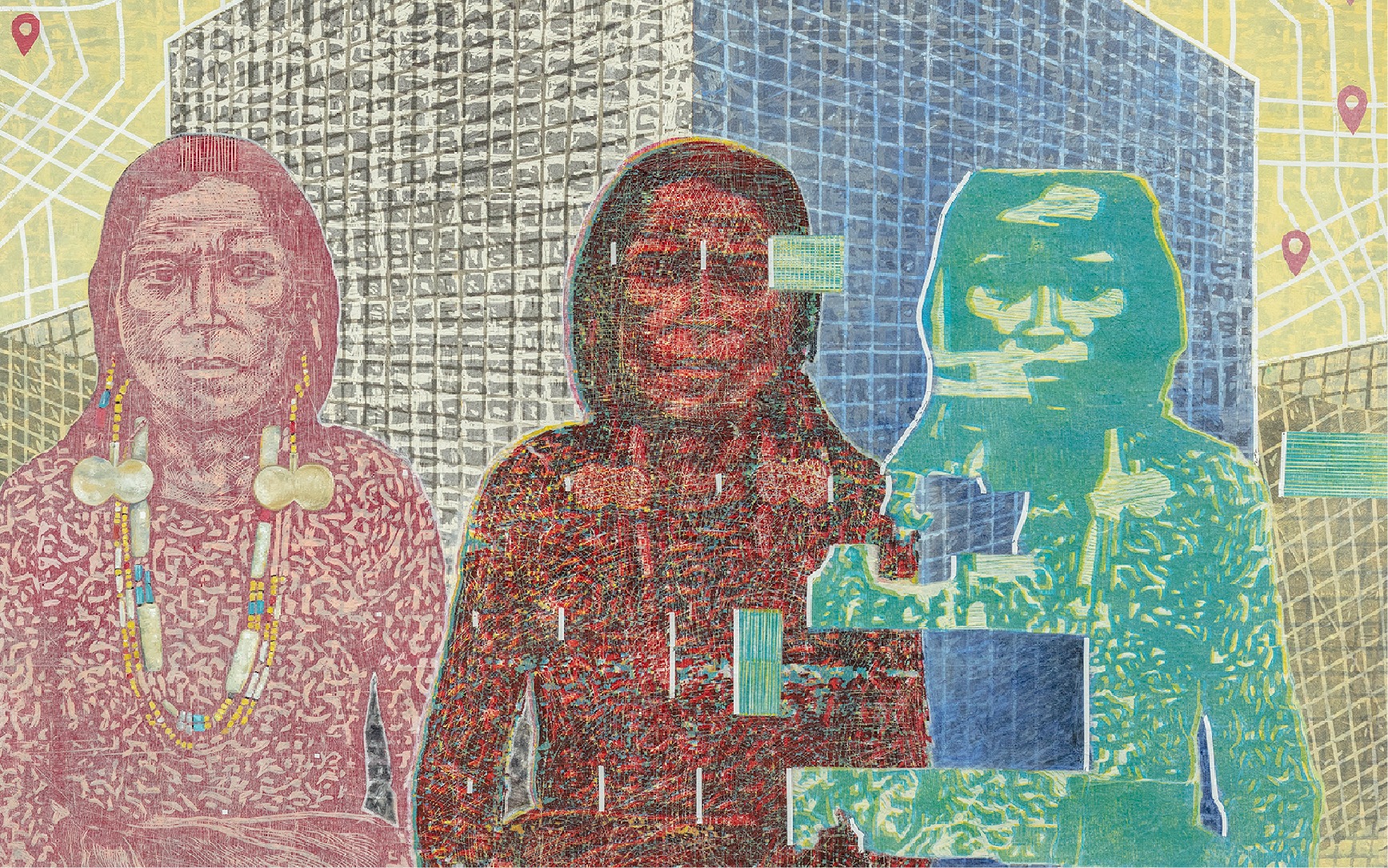

In one of his pieces, Aguinaldo references a colonial image of Igorots gazing at rice terraces. He superimposes the view of terraces with giant blocks resembling modern buildings and teeming with the iconic drop pin symbol. In another work, a local is poised atop a horse as if surveying the land. But the mountain trails are missing, and Aguinaldo paints a map of a city. The artist connotes converting agricultural gardens into grotesque tourist theme parks, a current and popular economic choice for landed locals.

Aguinaldo, whose house sits on the side of a mountain overlooking La Trinidad Valley and parts of Baguio City, noticed a more-than-usual surge of construction projects during the COVID-19 pandemic. He began a series of depictions of locals riding horses overwhelmed by expansive converging grids and matrices of street maps and high-rises. While the city acquiesces to pernicious infrastructure-based economies, Aguinaldo observes and engages with local resistance from the city’s complex highland and lowland culture. Indigenous communities, other than the original native Ibaloi of metro-Baguio, and lowlanders have been moving in and out of the city in fleeting or drawn-out migrations.

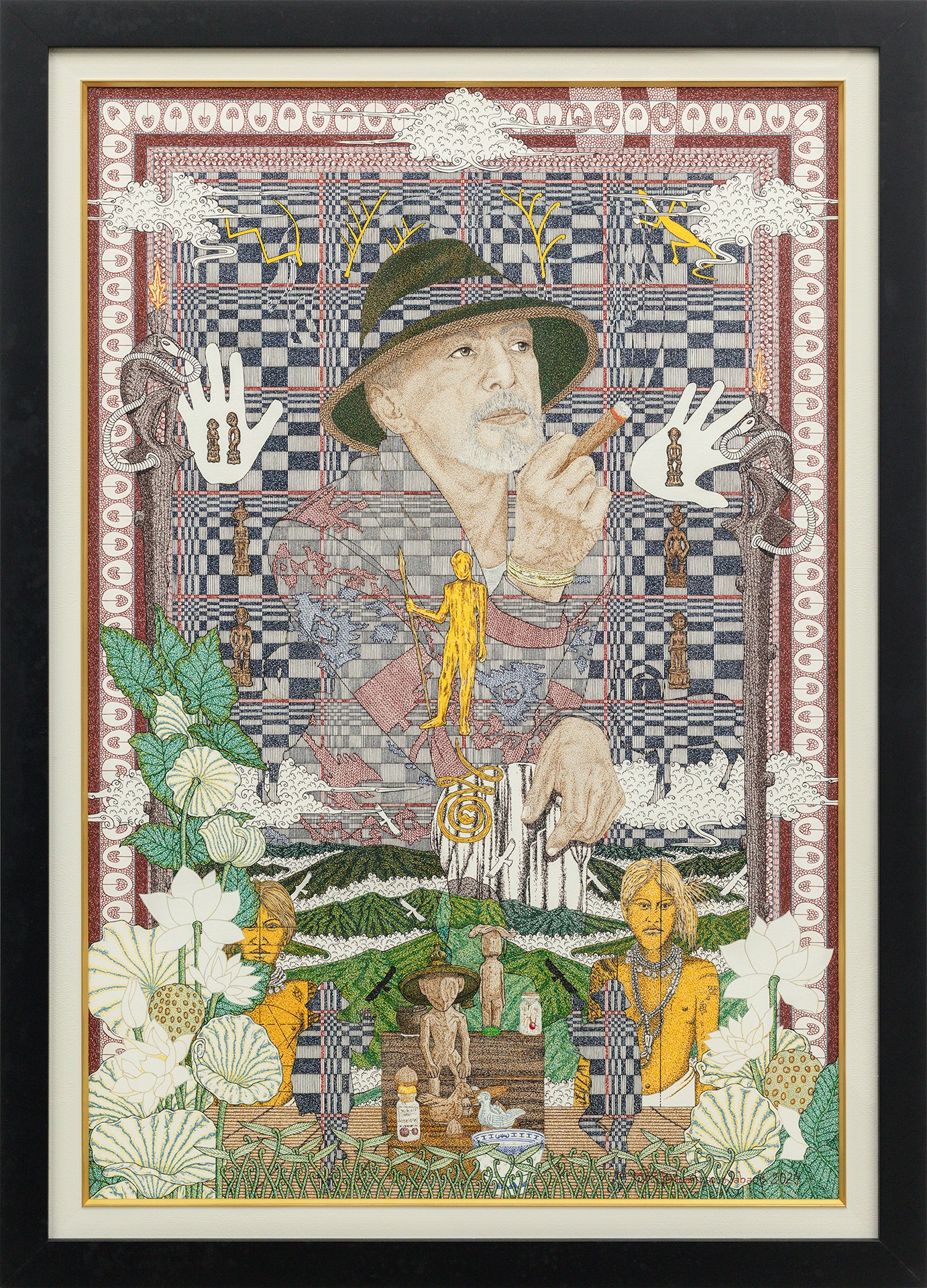

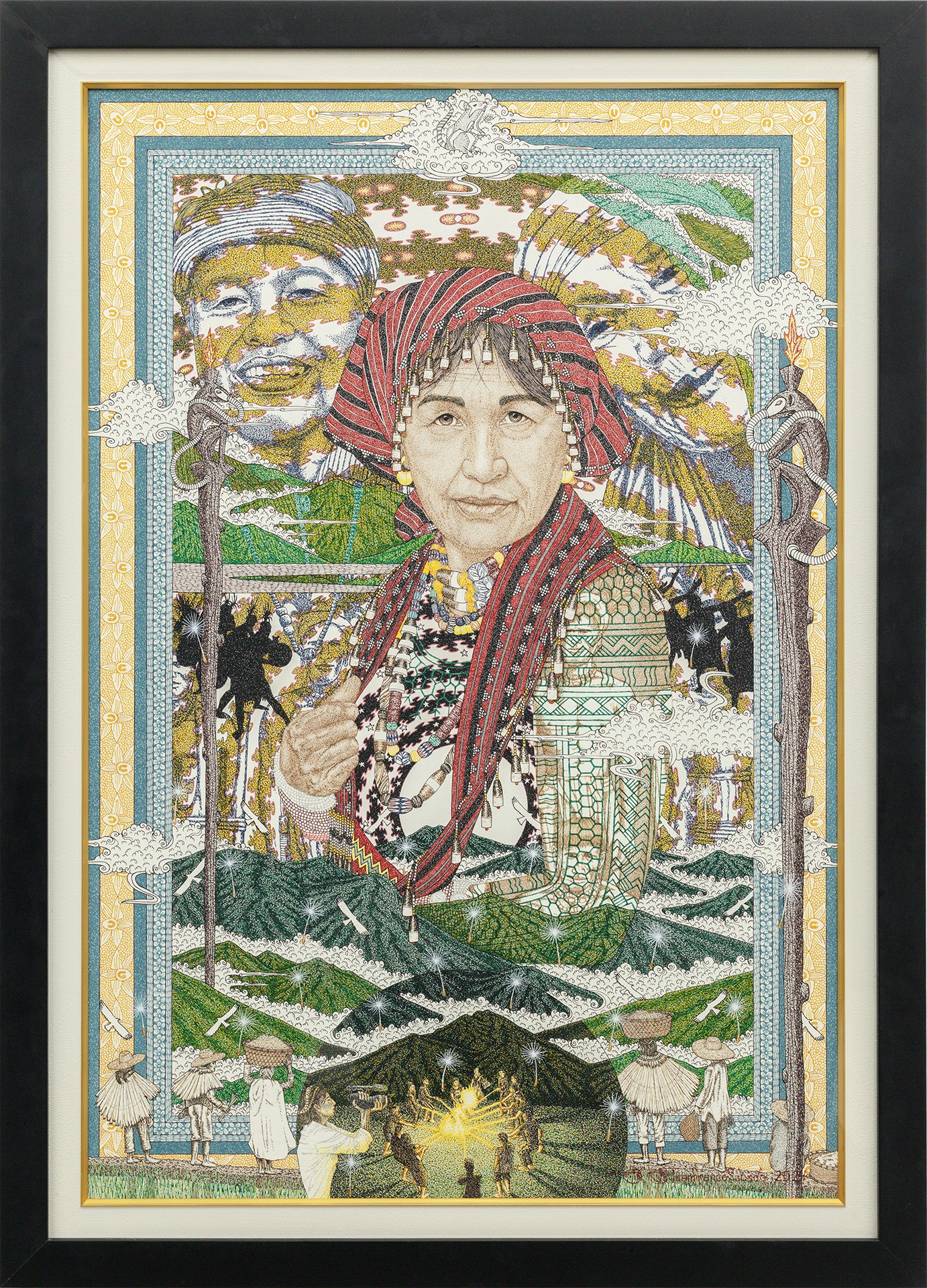

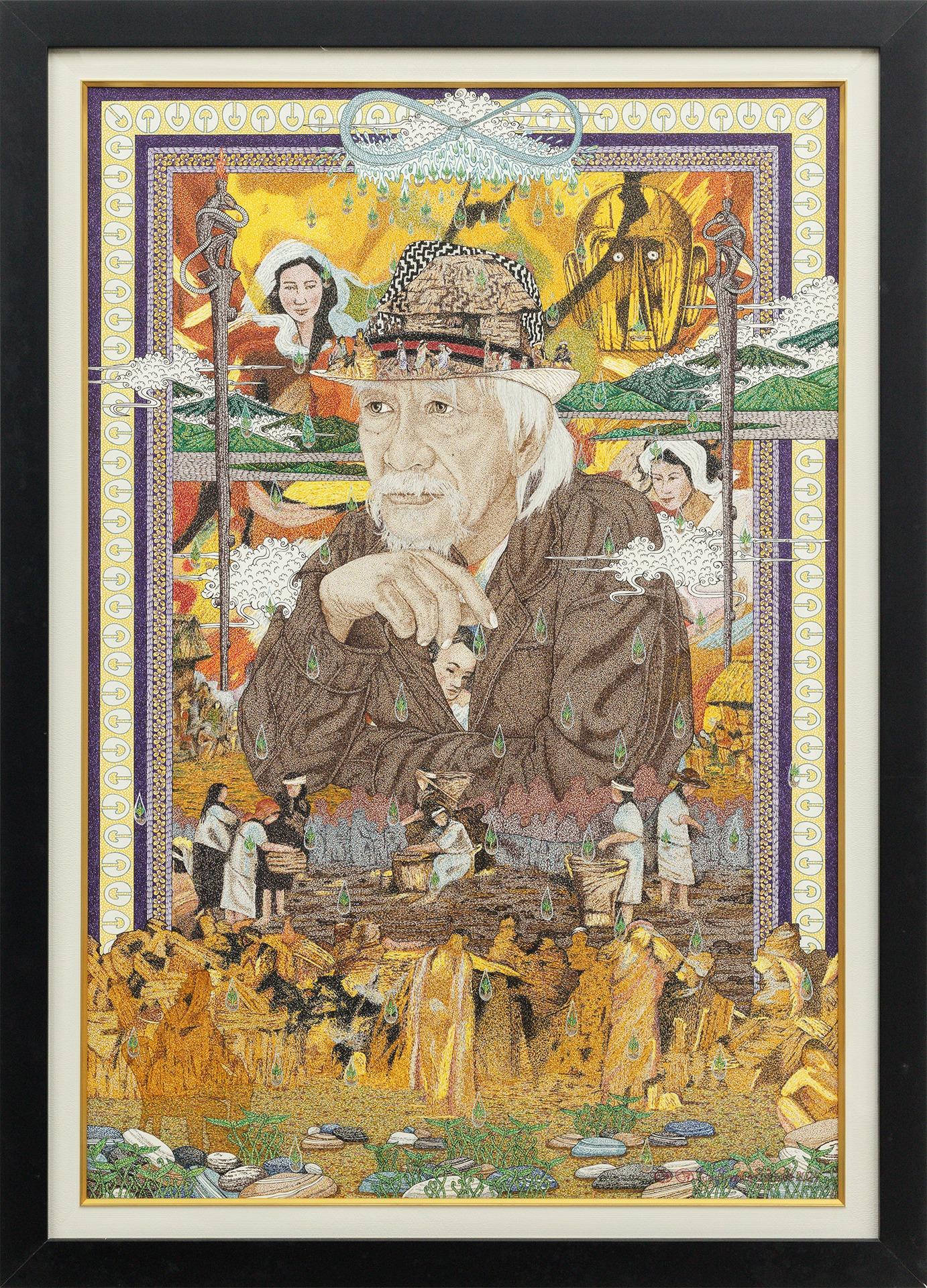

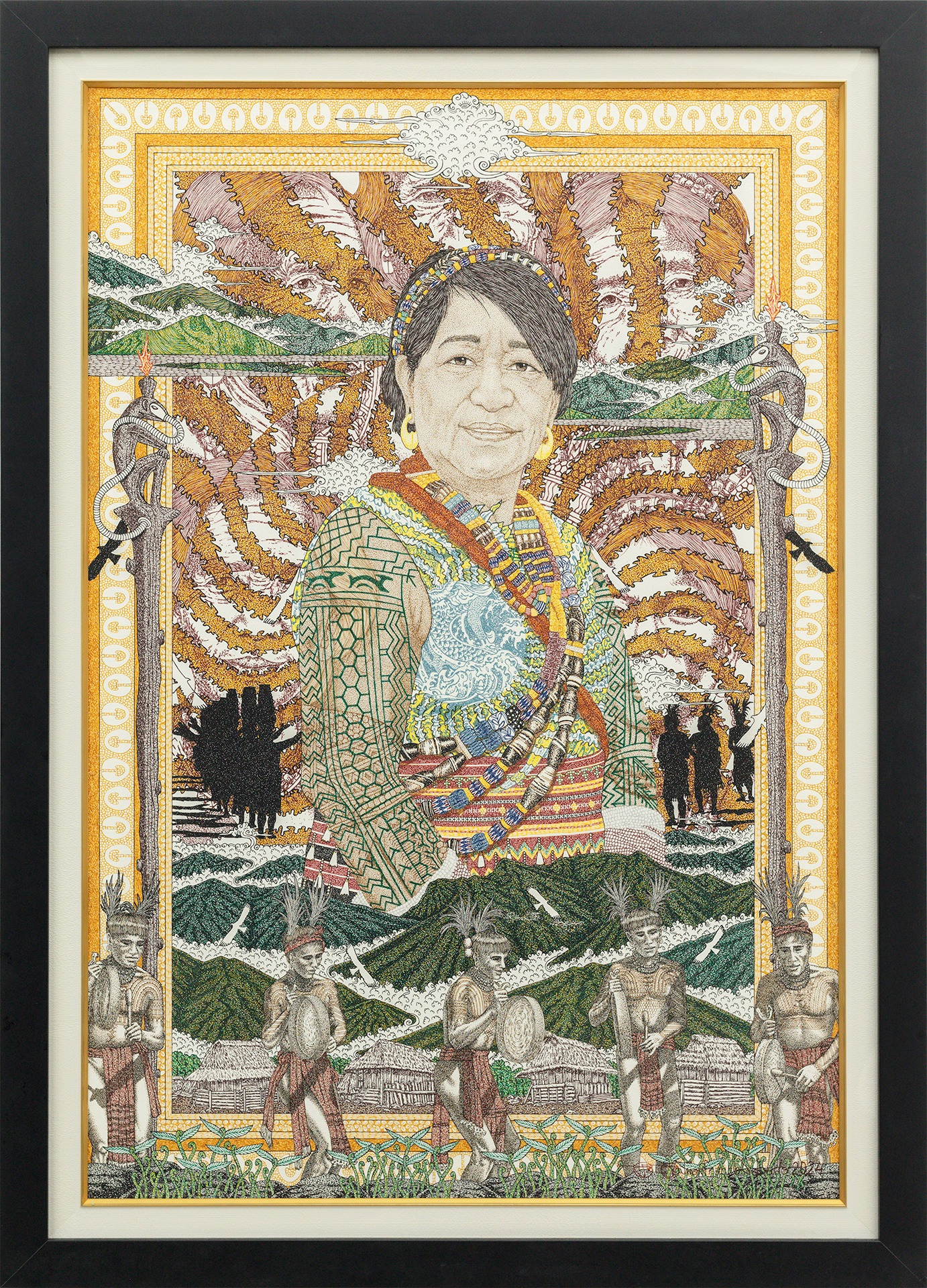

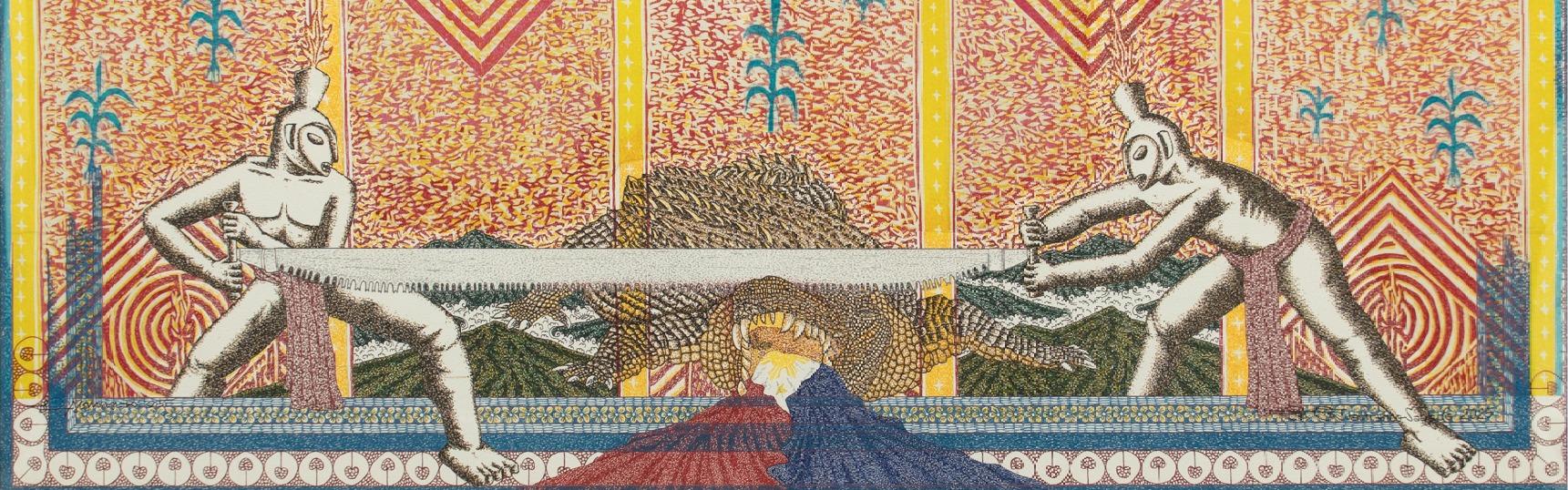

Sabado’s portraits, on the other hand, offer a sentimentality about traditional knowledge transmission. In a way, there is a persistent reiteration of Cordilleran communal value systems. The artist has, over time and in his performance art, reflected on the spiritual body as an ecological warrior from a composite of teachings gathered since the 1980s from the personalities or culture-bearers he now honors here. In previous public performances, Sabado embodied the persona of the Ecowarrior, a sublime figure covered in orange mud and wearing a gas mask. The performance contends with the impending doom from ecological disaster, our botched relationship with the technological modern, needed radical social actions inspired by Indigenous systems, and the length of time that nature auto-heals from rapid anthropogenic catastrophes.

In his portraits, objects and scenes surround each of the subjects, building on the world where each operates. But the choice of elements also reveals Sabado’s learnings. He speaks of an artist who has introduced him to the medium of pen and ink, two Kalinga women leaders who have devoted their lives to sustaining Indigenous traditions, a mambunong who is a master in the Madmad ritual of the Ibaloi, an Indigenous impressionist artist who has for decades faithfully painted Ibaloi lifeways, and a mumbaki who taught him about Ifugao spirituality. Coming from his experience, Sabado implores the value of culture-bearers for the community’s youth.

Both artists situate their practice around cultural migrations within the Cordillera Region and its neighbors. The region has changed borders more recently over time under different political shades and agendas. In 1908, the American occupation separated the highland from the lowland. Later, in the post-war break-up that undid this separation, most of the highland part was left neglected by the state. The present borders were formed by a struggle for autonomy that was partly conceived right after the fall of the Marcos dictatorship in 1986. This region of Indigenous peoples who have maintained resistance and distinctive communities since pre-colonial times is where both artists’ families have migrated to and integrated their lives. Aguinaldo was born and raised in Baguio City, and Sabado in the mining town of Lepanto in Mankayan, Benguet.

Each artist presents works that are informed by local indigenous relationalities profoundly scrutinized in the mid-1980s by the Baguio Arts Guild. The city, at that time, could be described as a regional art center when the words ‘art’ and ‘collective’ were beginning to be compounded locally. Sabado and Aguinaldo started as young members in the guild founded by artists like Santiago Bose, who espoused socially-engaged modalities in the guild festivals.

In the decades following, the practices of both artists have continued to engage local relationality, protest, belongingness, Baguio City’s pan-indigeneity, and their autobiographical and topographical placements in this history. They have consistently produced works that are unmistakably concerned with the visual culture of the region and the futures that are formed by incessantly seeing more than the sum of parts.

Words by Rocky Acofo Cajigan

Leonard Aguinaldo (b. 1967, Baguio City, Philippines; lives and works in Baguio City, Philippines) is a Baguio and Benguet-based artist whose practice is inseparable from the highlands that raised him. Known for his masterful carving on wood and rubber, he transforms these humble materials into striking relief prints and mixed-media works that feel both ancestral and contemporary. His pieces function as vivid ethnographic records-reverent yet unafraid to be satirical-capturing the cadences of local life, the humor folded into everyday customs, and the quiet spiritual worlds that hover beneath Cordilleran culture.

Over nearly two decades of artistic practice, Aguinaldo has built a body of work that stands as both cultural testimony and creative innovation. His artworks, exhibited widely in the Philippines and internationally, are celebrated for how they champion the narratives of upland communities.

His deep immersion in community life continues to be the force that animates his work. Rather than observing from afar, Aguinaldo moves within the highland cultures that inspire him-listening, learning, absorbing the stories that become the backbone of his imagery. In doing so, he creates art that is not merely about place, but from place: textured with memory, weighted with meaning, and anchored by the people whose lives he honors.

Today, Leonard Aguinaldo remains one of the most distinctive voices in Northern Luzon's contemporary artscape. His works serve as a bridge between past and present, local and global, personal and communal-holding space for a people's story, carved with both tenderness and truth.

John Frank Sabado (b. 1969, Mankayan, Benguet, Philippines; lives and works in Baguio City, Philippines) is a self-taught artist whose works show a remarkable deftness at using the painstaking pointillist approach to forming images. Over the years, his works have become more textured and nuanced, revealing his intellectual and spiritual growth as an artist.

His meticulously detailed pen and ink drawings lend his surfaces “a peculiar mesmerizing effect.” Far from merely mesmerizing his viewers, John Frank’s works in this exhibition have a story to tell. The visual elements are more than embellishments as each represent something about the subject’s life and work. The portrait in its entirety is so rich in imagery that even after looking at it for long periods, a viewer sees more when he/she returns to it.

Beyond the ability to unify and assemble varied elements to become a composite image, his works bear evidence of the artist’s active processing of his subject’s life and work in forwarding cultural art forms, beliefs, and traditions.

He succeeds in using a visual language that resonates with his conviction that the arts should continue “to provide imaginative, moral, and spiritual sustenance for individuals and communities.”

John Frank, born to Ilocano parents, grew up in a largely Kankana-ey community in Lepanto, Mankayan, Benguet. He would spend every summer for three consecutive years in Hapao and Guhang, Ifugao. When he was 16 years old he joined his father’s road construction project and lived as part of those communities. Only several years later did he realize how his exposure to traditional practices of the Kankana-ey and the Ifugao left an indelible imprint on his consciousness. His works in this show usher in an entirely new phase in his growth as an artist.

He is a member of the group Kalasag formed in the early 1990s with fellow artists Leonard Aguinaldo, Gen Alangui, and Jordan Mang-osan.

He has mounted 15 solo exhibitions since 1994 and joined over 40 group shows. He was a finalist in the Philippine Art Awards in 2000, 2003 and 2014 and Juror’s Choice in 1999 and a recipient of the Thirteen Artists Award (2000), Cultural Center of the Philippines. He has exhibited in Japan, Australia, China, Malaysia, and in other Southeast Asian countries.

Installation Views

Works