Mare Fecunditatis

Yasue Maetake

Silverlens, Manila

About

Clarity in Reductionism: Yasue Maetake’s Sculptural Bodies

By Yayoi Shionoiri

All successful life is

Adaptable,

Opportunistic,

Tenacious,

Interconnected, and

Fecund.

Understand this.

Use it.

Shape God.

~from Earthseed, Parable of the Sower by Octavia Butler

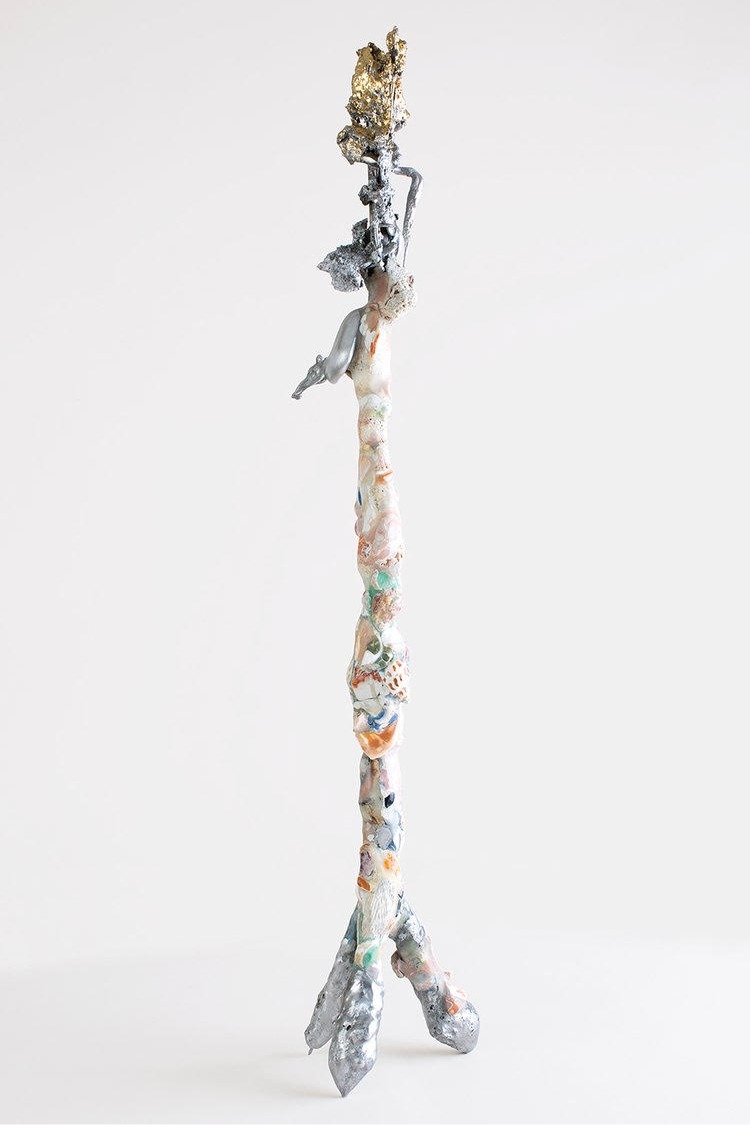

Mare Fecunditatis – resurrection (2025) by Yasue Maetake makes its presence known before me in all of its 8-foot, 160-pound presence. A steel carriage, resembling the fossilized backbone of a prehistoric creature, lumbers horizontally and anchors the sculpture. Organic matter, sealed by a combination of epoxy and urethane resin, covers this armature. Upon closer inspection, the components of the organic matter reveal themselves: bits of bleached white and peach pink coral; animal bone and fossil shards; sea glass in shades of bottle green; lapis lazuli the color of saturated navy; cloudy green fluorite; grape purple raw amethyst; raw quartz of varying shades; alabaster and marble chunks; and seashell fragments. Mare Fecunditatis seems like she could be exhibited either on a sandy beach or in a fabricated outdoor space.

Maetake’s other sculptural bodies in the exhibition also exude quiet, but powerful bearings. Some, like Primordial Soup (2023-2025) and Neuro Estuary (2025), stand vertically like protective sentinels, while others, like Ceremonial Delta I, Ceremonial Delta II (both 2025), and Mare Fecunditatis – fetus (2025), extend out like rhizomatic protrusions from the wall. Maetake’s sculptural bodies are simultaneously familiar and ever-so-slightly menacing. If not for the certainty of Maetake’s creative volition, it might be difficult to determine whether Maetake’s work was excavated from the past or sent to us from the future.

While Maetake has named Mare Fecunditatis after both a lunar mare in the eastern half of the moon and Japanese author Yukio Mishima’s tetralogy (1969–1971), I found myself instead reflecting upon Parable of the Sower (1993) by Octavia E. Butler. Set in a speculative 2027 California, riddled by climate collapse and social disintegration, Butler’s novel follows Lauren Olamina, a young woman who creates Earthseed—a belief system that is, at once, a mode of survival and a guiding vision, simultaneously articulating the brutality of Olamina’s present and offering an adaptive framework for an unknown future. Earthseed allows Olamina and her community to find meaning in disaster—and, perhaps more significantly, to act to shape a new world, rather than merely endure the old one. Olamina remarks that “[c]hange is ongoing. Everything changes in some way—size, position, composition, frequency, velocity, thinking… Every living thing, every bit of matter, all the energy in the universe changes in some way.” In this adaptive mode of survival, Olamina seems to be working through and acknowledging the contradictions of a belief system that is about both present and future, as she seeks to retain autonomy while reacting to external change.

I see a similar negotiation in Maetake’s practice. The sculptural bodies in this exhibition advance a lineage from Maetake’s past works while offering further clarity in her artistic method. Maetake refers to the organic matter found in Mare Fecunditatis and her other sculptural works as prima materia, a proprietary blend of calcium, other minerals, polymers derived from marine organisms, animal bones, fossils, and various gemstones. This material is then finished by Maetake using stone-polishing techniques. In this way, Maetake is not merely an assembler of found objects; she is the creator of the very substance of her work. Her agency is evident not only in the creation of these material bodies but in what she allows to fall away from the raw material.

Maetake describes her sculptural method as a process of reduction—a distillation in which excess is removed to reveal that which is fundamental. To me, Maetake’s process echoes Olamina’s recognition that one is both an agent of, and deeply affected by, change. Maetake serves as an agent that is moved: an exploration to seek understanding of her materials, described by her as the “self-evident existence of the physical matter.” To that end, her work is both grounded in the present, but directed towards a future not yet apparent.

Maetake’s creative action channels the accumulated energy of her materials to realize forms that speak across time. Ultimately, Maetake’s sculptures feel like physical accumulations that result from a series of ongoing challenges—Maetake’s responses to chaos, randomness, and passivity. Imbued with a constant fluctuation that is neither reactive nor inert, Maetake’s work oscillates between a solid state, based on the laws of physics, and an intimation that change is the only constant. In this clarity, and in this commitment to shaping through subtraction, Maetake gives form to that which is timeless, and urgently, unmistakably timely.

Yasue Maetake (b. 1973, Tokyo; lives and works in New York) is a Tokyo-born artist living and working in New York City. Her work has been exhibited at numerous national and international institutions such as Espacio 1414 at the Berezdivin Collection, San Juan, Puerto Rico; Queens Art Museum, New York; 10th Sonsbeek, Arnhem, Netherlands; and ASU Art Museum, Arizona, amongst others. Solo exhibitions include Fons Welters, Amsterdam, The Chimney, New York, Microscope, New York, and Nina Johnson, Miami, and others.

Maetake’s work has been featured in Sculpture Magazine and reviewed in Artforum, The New York Times, ArtAsiaPacific, FlashArt, amongst others. Maetake was named one of “20 international women advancing the field of sculpture” by Artsy, is a recipient of the NYFA Fellowship in Sculpture, and she also completed a residency in the studio of El Anatsui in Ghana sponsored by a research grant from the Agency for Cultural Affairs of Japan. In summer 2024, Maetake’s essay centered on Eva Hesse will be published in Transatlantique Collection, Paris. Yasue Maetake earned her MFA from Columbia University in New York.

Installation Views

Works