There is Still a Tomorrow, Mother

Imelda Cajipe Endaya

Silverlens, New York

About

Imelda Cajipe Endaya is renowned as an artist, activist, and feminist in the Philippines. “There is Still a Tomorrow, Mother,” her first exhibition in New York in nearly twenty years, presents a concise overview of her distinguished career, which spans over five decades. The exhibition introduces her singular blend of artistry and activism to new audiences at a moment when many people are considering the role art and culture can play in resisting political repression.

Cajipe Endaya was born and raised in the Philippines and began her career under the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos. After graduating in 1970 from the University of the Philippines’ College of Fine Arts, she started as a printmaker, creating work that drew upon historical source material.

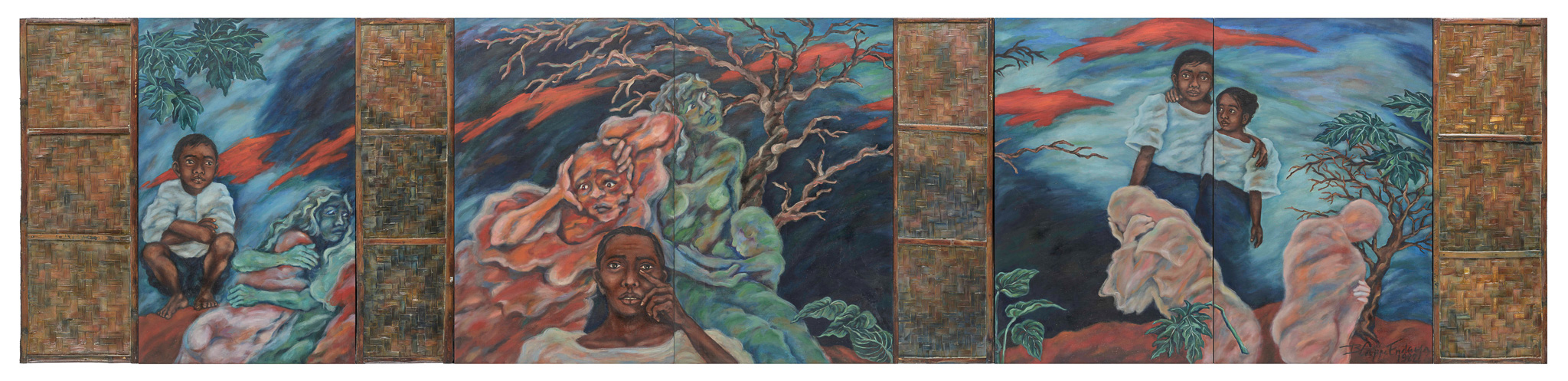

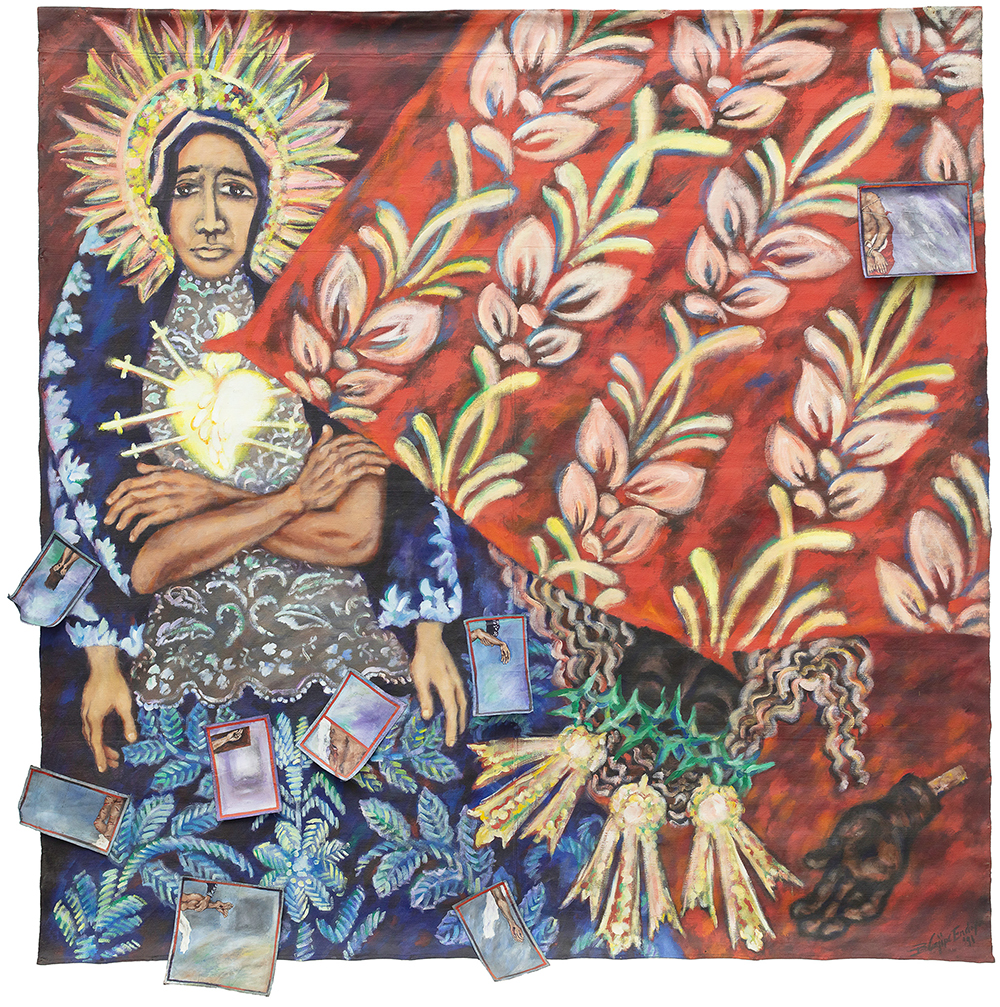

The 1980s saw significant shifts in her approach to materials and content as she came into her own as an artist. Cajipe Endaya took up painting as a platform to highlight pressing socio-political issues and their impact, centering women and families as protagonists. The themes of May Bukas Pa, Inay (There is Still a Tomorrow, Mother), 1982, a multipaneled painting addressing the threat of nuclear disaster, and Daing Ng Puso (Heart’s Plaint), 1985, which protests the massive military presence of a U.S. base on Subic Bay, reflect her new art of refusal and defiance. These paintings also embody Cajipe Endaya’s expansive approach to the medium. Along with expressively rendered figures, the paintings incorporate materials, in this case, sawali (bamboo mats) pulled from her windows, giving the canvases an intensely physical presence. Her creative recycling of materials from her own home is emblematic of the way her art emerges organically from the circumstances of her life.

Cajipe Endaya’s artistic priorities evident in these paintings, responded directly to the political unrest in the Philippines. Nineteen eighty-three saw the assassination of Marco’s political opponent, Benigno Aquino Jr., upon his return to the Philippines from exile in the U.S. An investigation revealed that the killing had been engineered by the military under a close associate of Marcos. The acquittal of those involved incited protests and demonstrations, which culminated several years later, in a bloodless revolution by citizens in greater Manila who rallied around anti-Marcos rebels stationed at Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA), forcing the Marcoses to flee.

In 2022, on the occasion of “Pagtutol at Pag-Asa (Refusal and Hope),” Cajipe Endaya’s retrospective held across the Cultural Center of the Philippines and the Ateneo Library of Women’s Writings, she recalled the decade of the 80s:

From 1983 the political movement against the Marcos dictatorship hurled me to heights of rage and protest. Necessity led me to incorporate palm leaves, grass texture, bamboo mat, other natural discards and recyclables onto my canvasses, even as I did organizing work with women artists and activists… I was inspired to do works on neo-colonialism, militarization, export of women’s labor, ill effects of globalization, all composed within the context of the imperiled home and threatened family life.

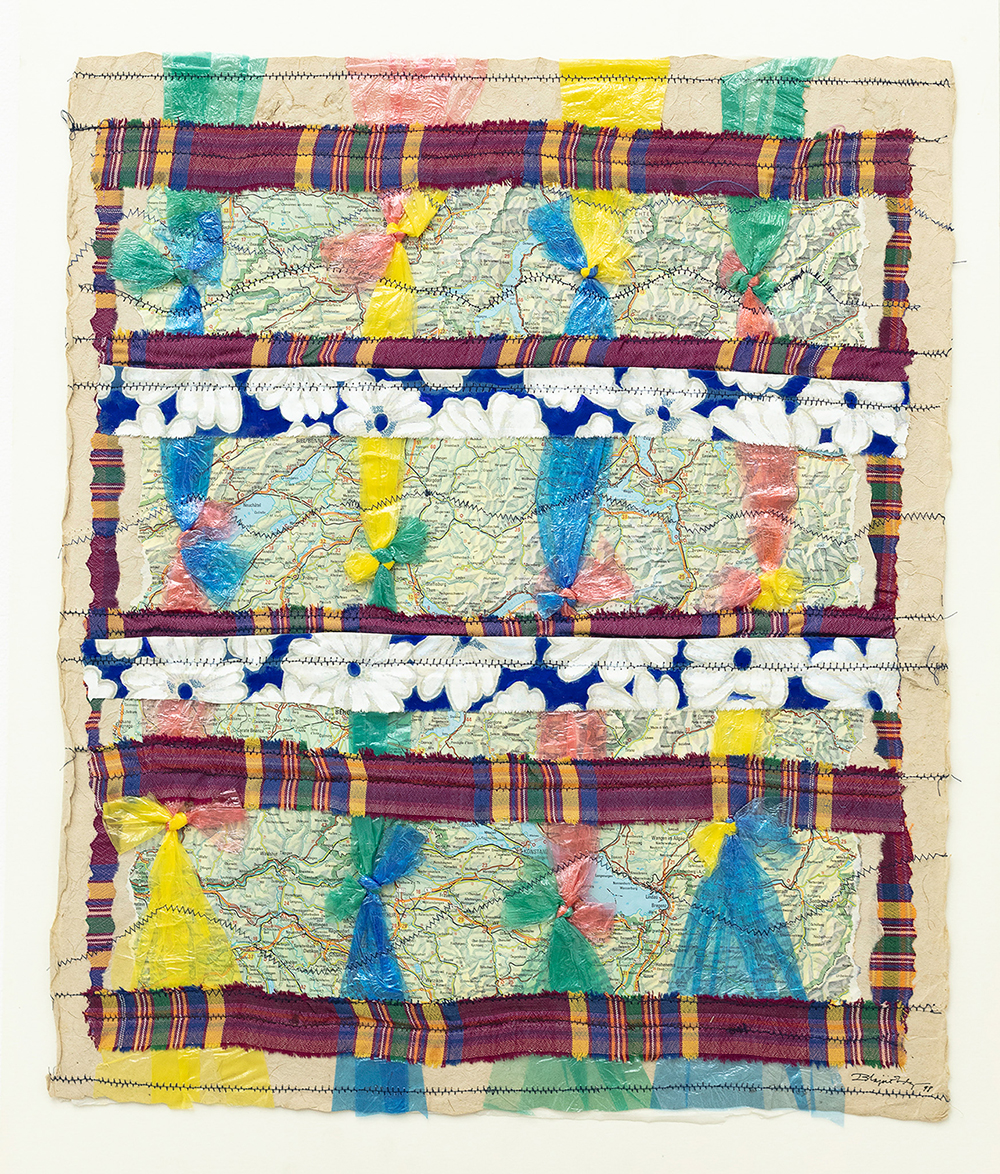

The themes laid out in Cajipe Endaya’s statement are on full view in this exhibition. Sugapa ang Pinoy sa Dayuhang Putahe (Colonial Mentality Tablecloth), 1989, an altered tablecloth, critiques the enduring legacy of a colonial mentality in the Philippines, including the devaluation of local labor in favor of imported Western goods. Tutol ni Dolorosa, 1991, examines two contrasting views of women: the precolonial Babaylan, a spiritual community leader, and the Spanish colonial Madonna, the suffering mother of Christ. An assemblage sculpture, The Wife is a DH, 1995, takes up the export of female labor, Filipinas who traveled abroad to take jobs as domestic helpers, and the cultural displacement as well as abuse they encountered. The print Pinoy Treasure Hunt III: Trails, 1998, made in Switzerland, also conveys a sense of dislocation by interweaving scavenged images of hidden treasure maps and things associated with that country with scraps of fabric and coconut tree bark from the Philippines to create a dense abstract pattern

During the 80s political upheaval in the Philippines, creative communities forged bonds, underscoring the power of collective action. A brief revival of democratic institutions following the flight of Marcos in 1986 and the swearing in of Corazon Aquino, Aquino’s widow, provided Cajipe Endaya and her cohorts with a window of opportunity for self-reflection and a broader consideration of female empowerment.

I also can’t help but remember the years 1983 to 1986, it was the cause for the dismantling of the dictatorship that made us women artists go beyond our windows, to get out of our doors – painters, playwrights, dancers and musicians alike – marching in the streets in unified protest…. The triumph at Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA) in 1986, which resulted in the dictator’s flight and subsequent reconstruction of democratic institutions, allowed us space and time to focus on our own situation as women. We noted that the images of women we made ourselves were always in relation to, if not in service of, others, as sister, as daughter, as wife, as teacher, as mother. As we shared each other’s life and work, we were spurred to continuously search for distinct womanly symbols.

What emerged out of collective political action was an understanding of collaboration as a significant force for enacting change. In 1987, the year after the deposition of Marcos, Cajipe Endaya was instrumental in founding KASIBULAN (meaning full bloom), a collective of women artists and arts professionals that is still going strong. KASIBULAN offered women a space of sisterhood and solidarity. On a practical level, this meant places to exhibit in a male dominated art scene. It also uplifted craft and traditional fabrics, categories which were less valued by the art world.

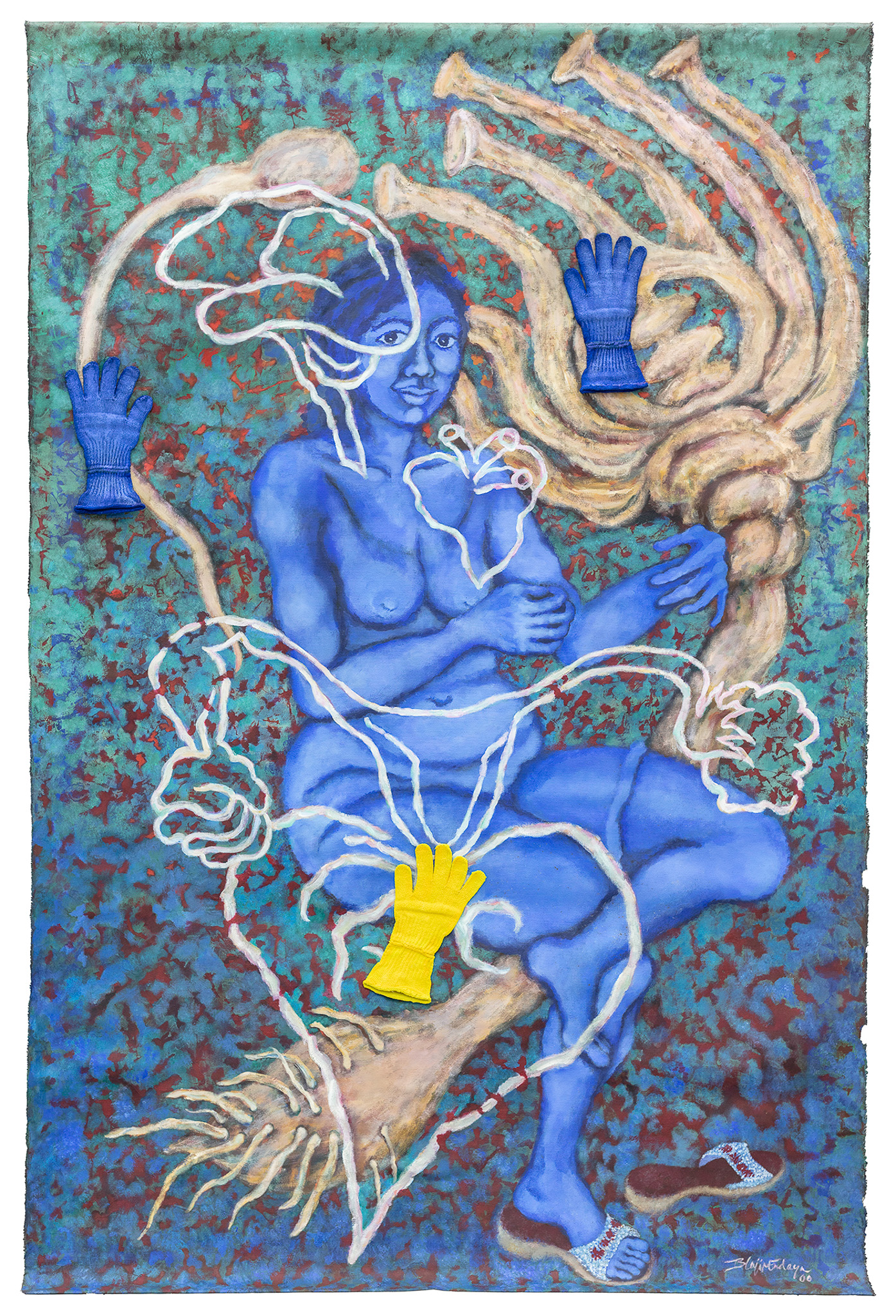

In the 1990s, Cajipe Endaya celebrated the collective in a pair of paintings. Kasibulan (Full Bloom), 1994, depicts a smiling woman overlaid with a heart, hand, and wings suggesting the joy and liberation embodied by this sisterhood. Pananalamin (Kambal Sibol) (Reflection (Twin Blooms)), 1994, shows mirror images of a woman overlaid with objects including books, a reminder that women might think beyond their familial roles, to the possibilities of education and self-improvement. The search for distinct womanly symbols seems to continue with Katawan Ko Pasya Ko (My Body, my choice), 2000, a work about bodily autonomy made in conjunction with an exhibition she organized about reproductive health.

More recent paintings show Cajipe Endaya’s continued commitment to foregrounding contemporary issues. Painted during the COVID-19 pandemic, Salinlahi'y Iligtas (Save the Generations to Come), 2020, a self-portrait as a tree with children playing in the branches, reflects her ongoing belief in the need to care for future generations. Referring to the political landscape, Banta ng Bulkan (Seismic Threat), 2023, calls for education for a working class long burdened by hunger and poverty—conditions that enabled a fraudulent election and the return to power of a deposed dictator’s family and their oppressive allies.

The phrase “There is Still a Tomorrow, Mother” encapsulates Cajipe Endaya’s priorities of family, community, and nationhood. It advocates for the necessity of living with hope, courage, optimism, and faith that there will be a tomorrow in the face of all odds. Through her activities as an artist, mother, engaged citizen, and community organizer, she embodies a model for living that resonates more powerfully than ever in the current global landscape.

–Eugenie Tsai

In celebration of There is Still a Tomorrow, Mother, Imelda Cajipe Endaya was joined by exhibition curator Eugenie Tsai last 10 May 2025 to explore the artworks in the exhibition. Read an excerpt here.

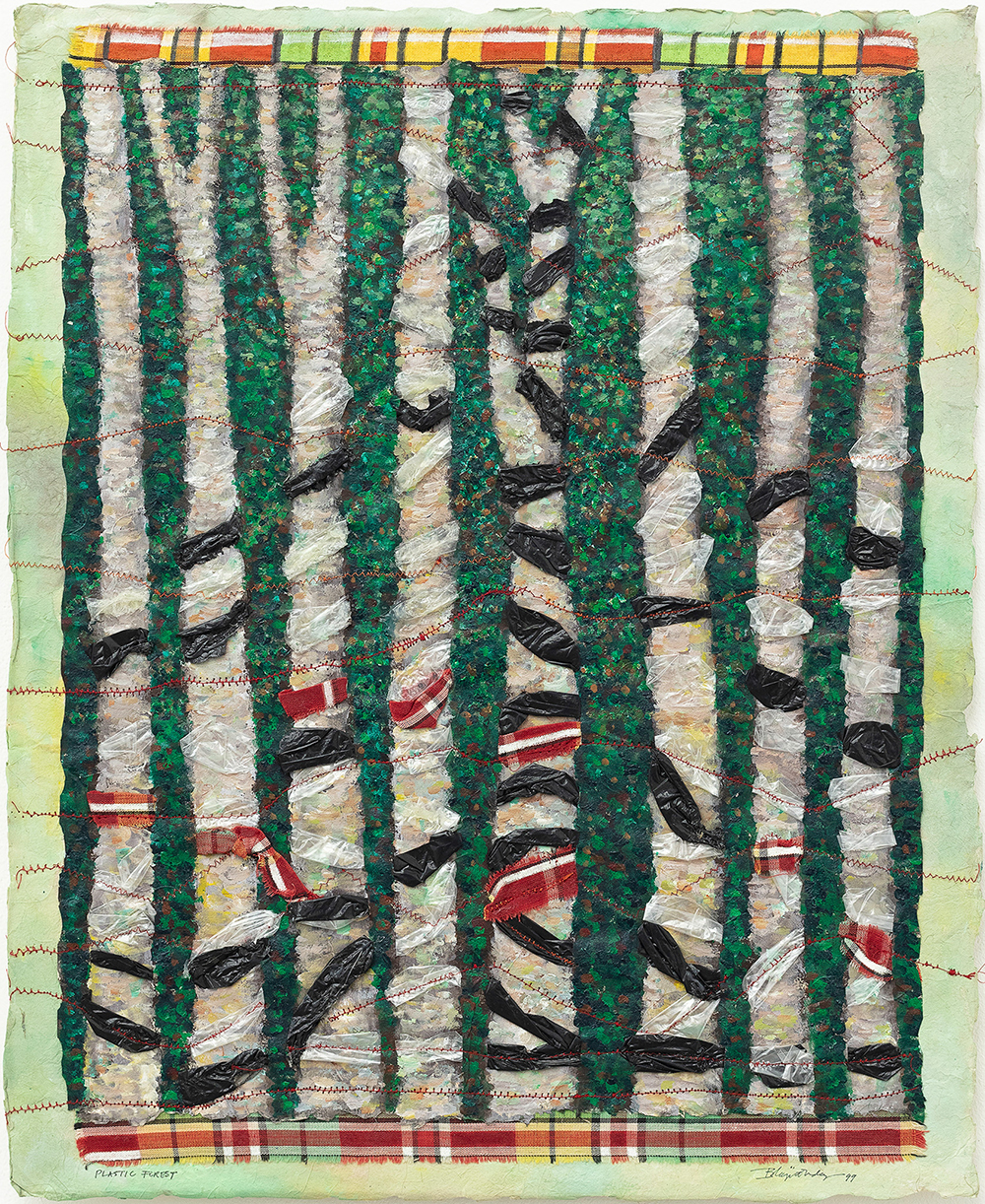

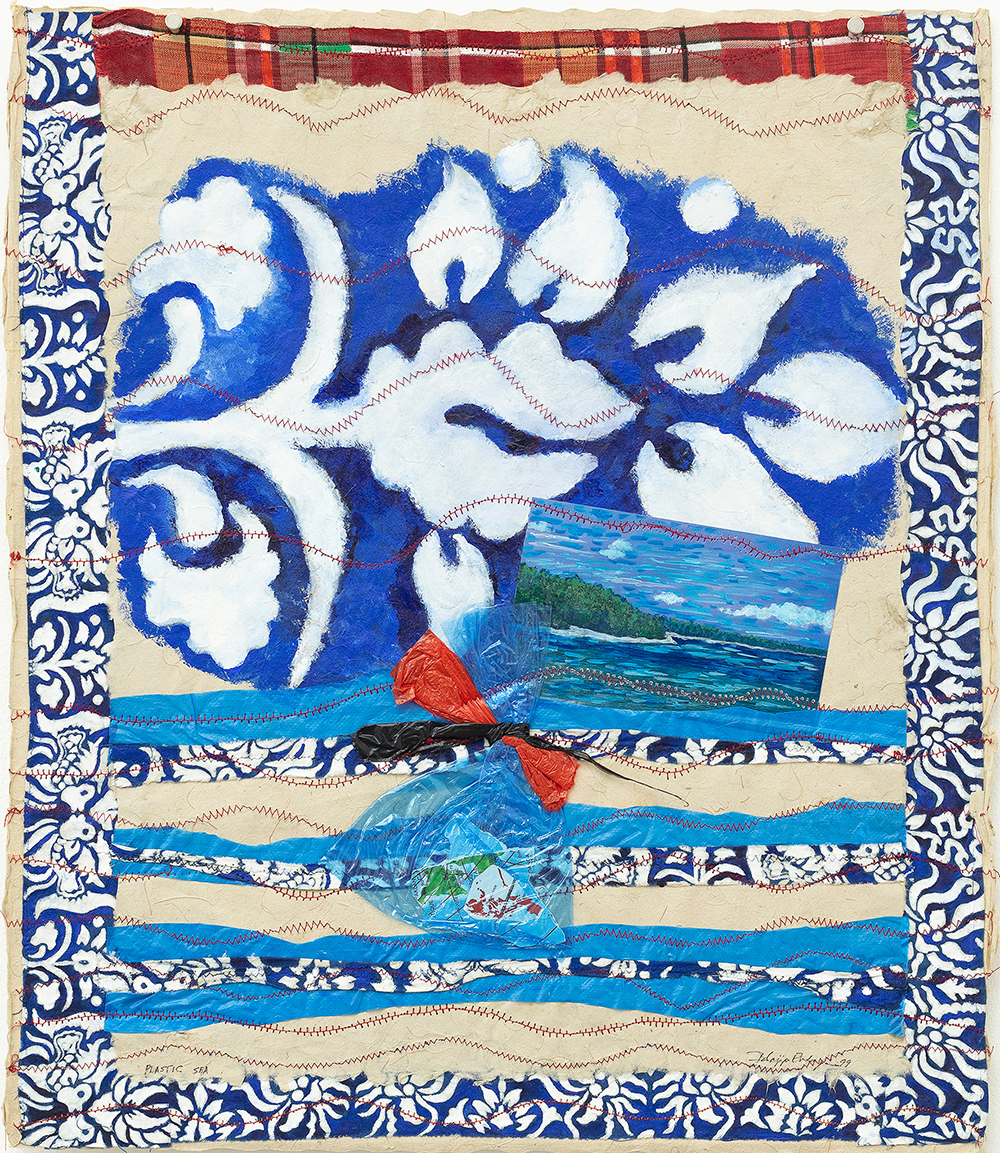

Imelda Cajipe Endaya’s (b. 1949, Manila, Philippines; lives and works in Manila) artistic career has been devoted to contemporary social issues from the viewpoint of women empowerment. In her art, she has dealt with issues such as cultural identity, human rights, migration, family, reproductive health, globalization, children’s rights, environment, and peace. Her mixed media paintings and installations are richly colored and textured with crochet, laces, textiles, window, flatiron, suitcases, papier mache craft, and found objects from home and popular culture. In 2022, Cajipe Endaya was the subject of a major retrospective staged across the Cultural Center of the Philippines and Ateneo Library of Women’s Writings, titled Pagtutol at Pag-Asa (Refusal and Hope). Other recent solo exhibitions include: Rigodon, Silverlens, Manila (2024); Abstracts (Early prints), Imagica Art Gallery, Manila (2022); and Caracol, Altro Mondo Art Space, Manila (2019).

Eugenie Tsai is a curator and writer based in New York. From 2007 – 2023, she was the John and Barbara Vogelstein Senior Curator, Contemporary Art at the Brooklyn Museum, where she oversaw the Contemporary collection, and organized loan and collection exhibitions. Exhibitions she organized include Oscar yi Hou: East of Sun, West of Moon (2022-23), Guadalupe Maravilla: Tierra Blanca Joven (2022), The Slipstream: Reflection, Resilience, and Resistance in the Art of Our Time (2021-2022) and KAWS: WHAT PARTY (2021). She also co-curated Crossing Brooklyn: Art from Bushwick, Bed-Stuy and Beyond (2014-15), and LaToya Ruby Frazier: A Haunted Capital (2013).

Prior to joining the Brooklyn Museum, she organized Robert Smithson (2004), which debuted at MOCA LA, before going on to the Dallas Museum, and the Whitney Museum of American Art (the exhibition received the International Art Critics first place award for best monographic show of 2005), and Robert Smithson Unearthed: Works on Paper, 1957-1973 (1991) at the Wallach Art Center, Columbia University. Eugenie worked at MoMA/PS1 as Director of Curatorial Affairs (2006-2007), and at the Whitney Museum of American Art (1994-2000) in several curatorial positions.

Installation Views

Works

The imported produce depicted here references the Import Liberalization Policy, a measure introduced under pressure from the World Bank as part of structural adjustment programs in the 1980s–1990s. While intended to stimulate economic growth, these reforms often deepened national debt and flooded local markets with foreign goods, undermining local farmers and industries.

In 1995, I exhibited my installation “Filipina DH” twice in Manila, at a time when controversies involving two Filipina overseas domestic workers were seething: the tragic execution of Flor Contemplacion in Singapore, and the triumphant Sara Balabagan case in the Middle East. My piece was a participatory work, where I asked for donations of maid’s uniforms and battered baggages. I hung the uniforms onto layers of clotheslines and projected on them various images of mothers/ mother surrogates and child, from colonial times to present. I laid out personal mementoes of overseas housemaids, all executed in mourning black, onto domestic labor implements, the way ordinary Filipinos would hang personal icons and souvenirs in their homes. - Imelda Cajipe Endaya

Amidst the challenge of a global pandemic and desperation over the climate crisis, what can a grandmother's dream for the future be? We, the older generation, are fading away from this grim world. But still we have productive time to rectify our generation's wrongdoings, guide and care for the future generations. Choose hope. Choose courage. - Imelda Cajipe Endaya