About

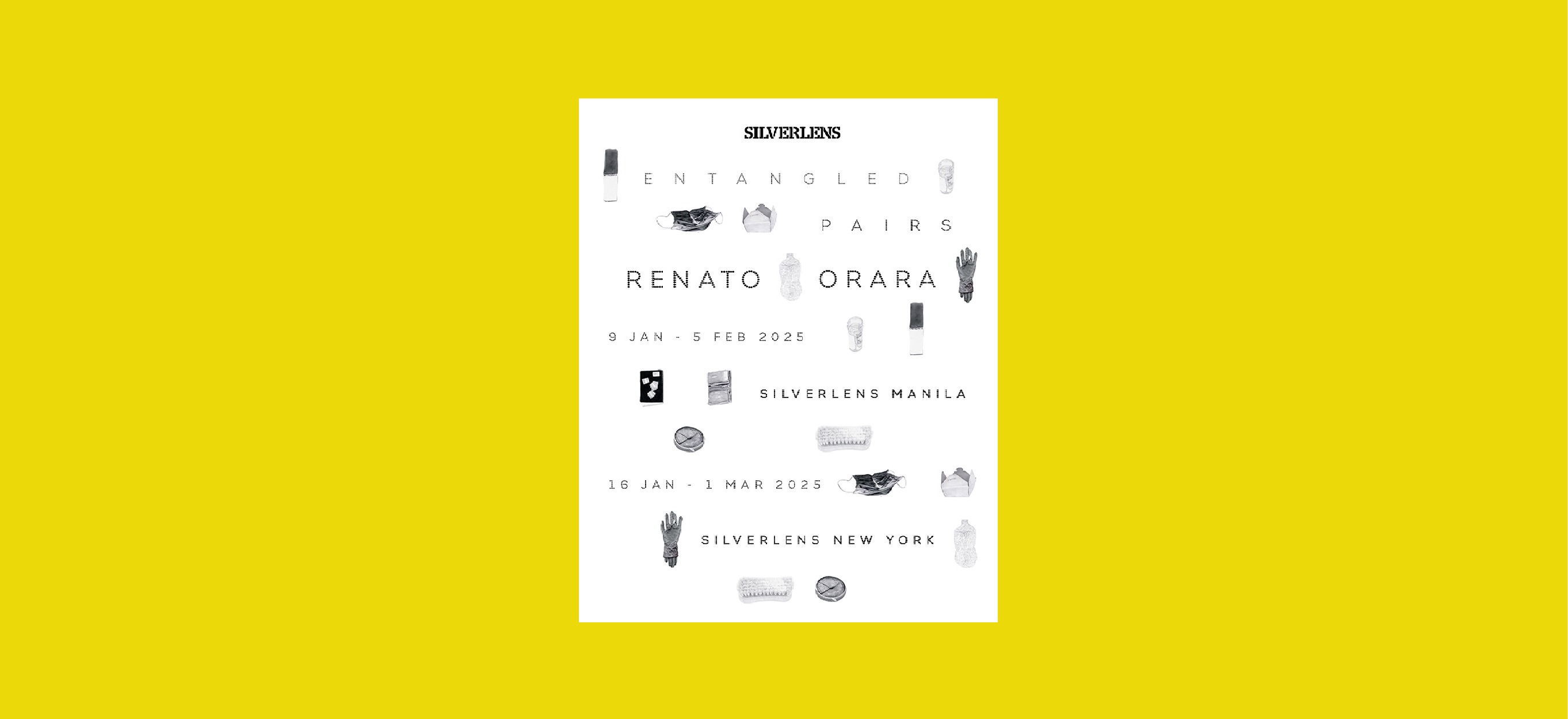

Silverlens is pleased to present Renato Orara: Entangled Pairs, a major cross-continental exhibition of the artist's work, staged simultaneously across Silverlens' Manila and New York galleries.

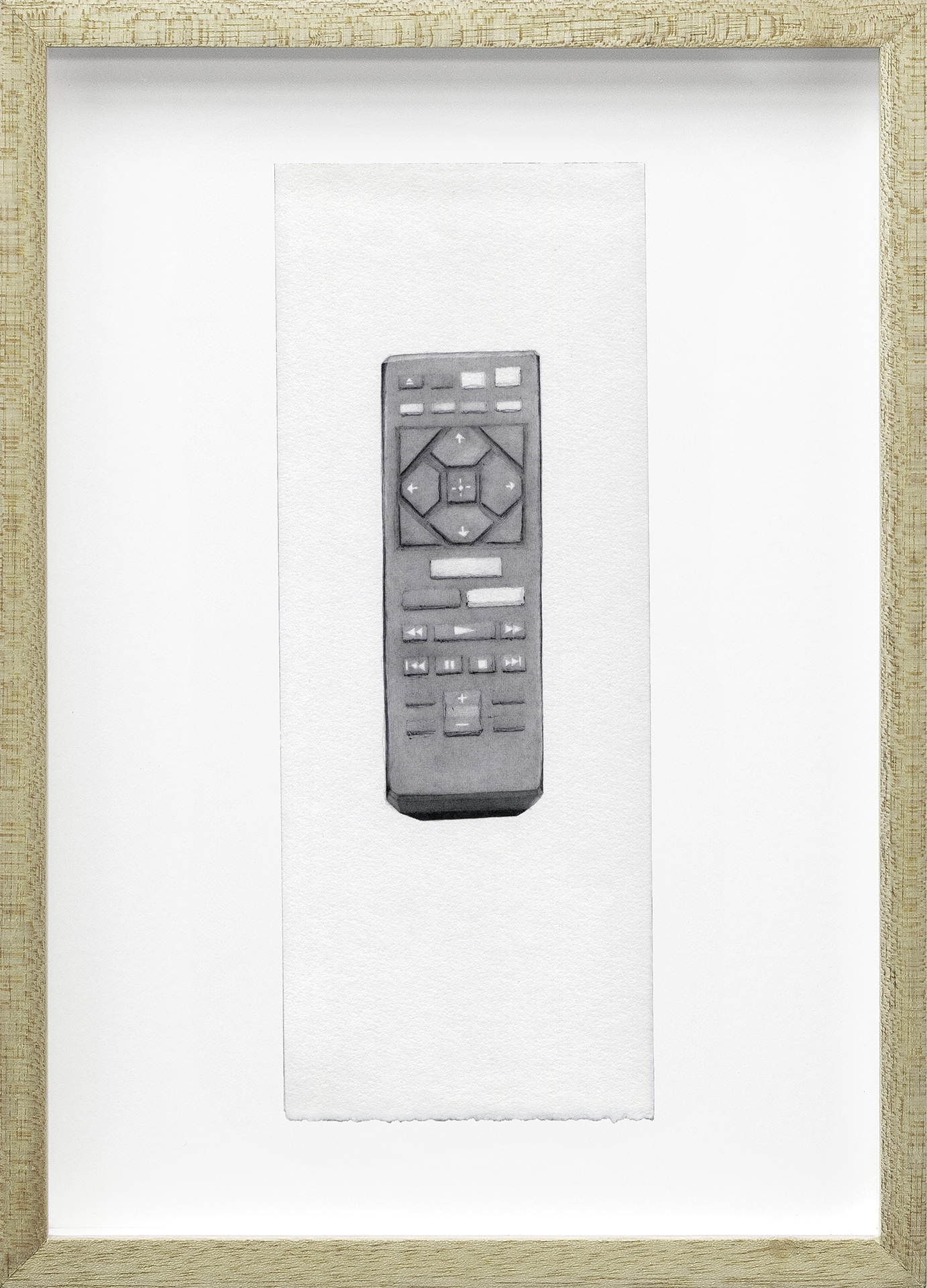

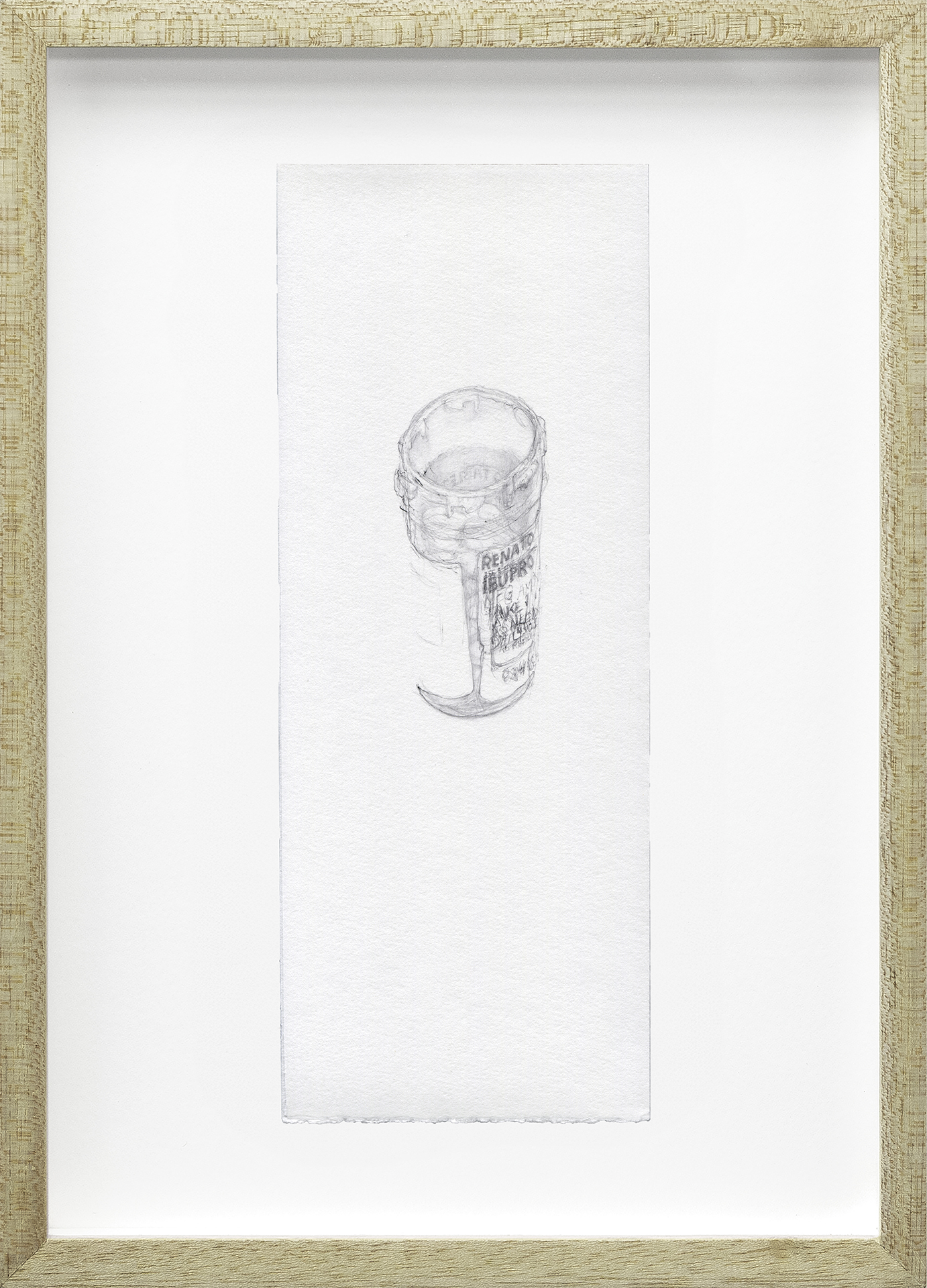

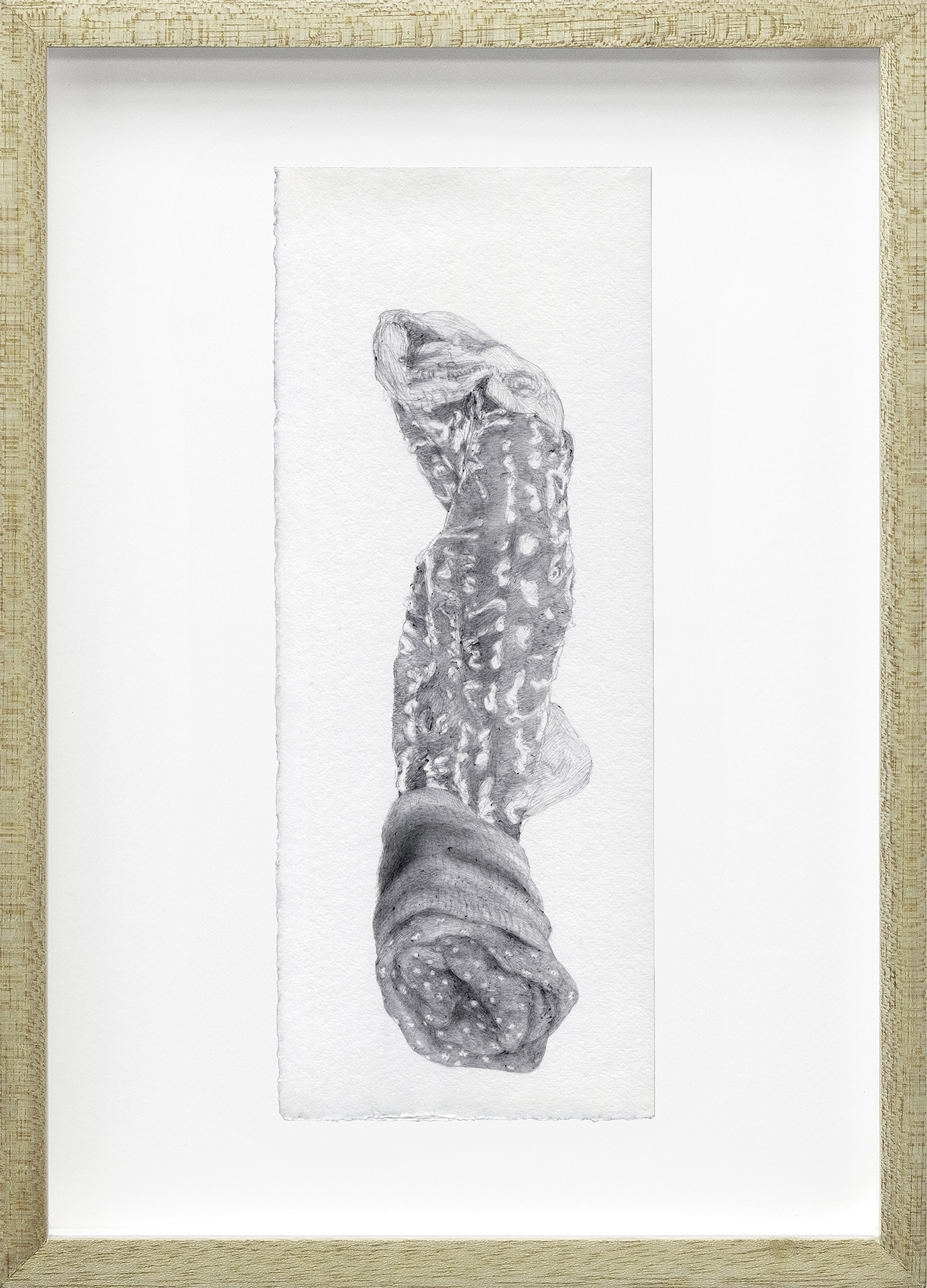

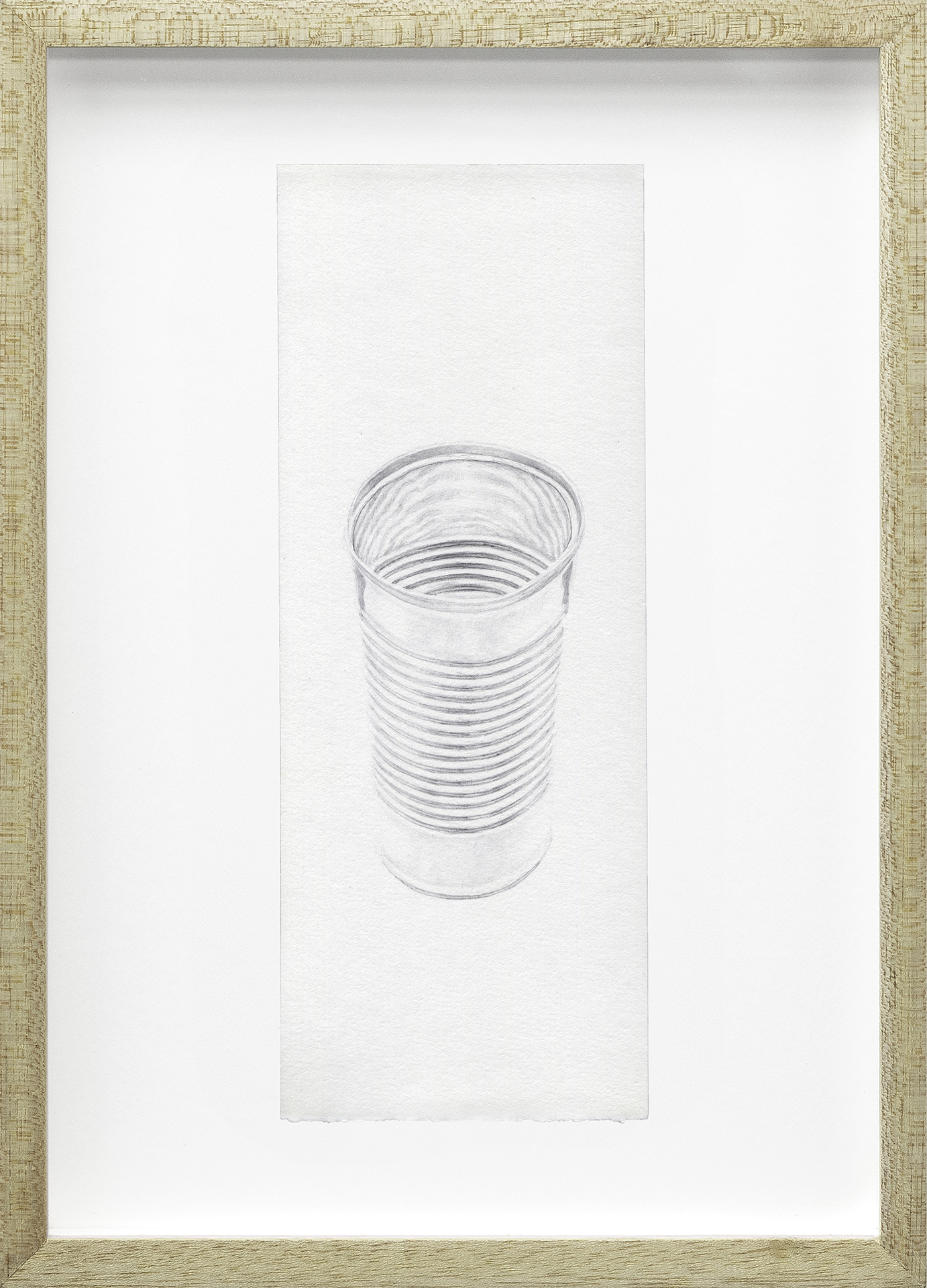

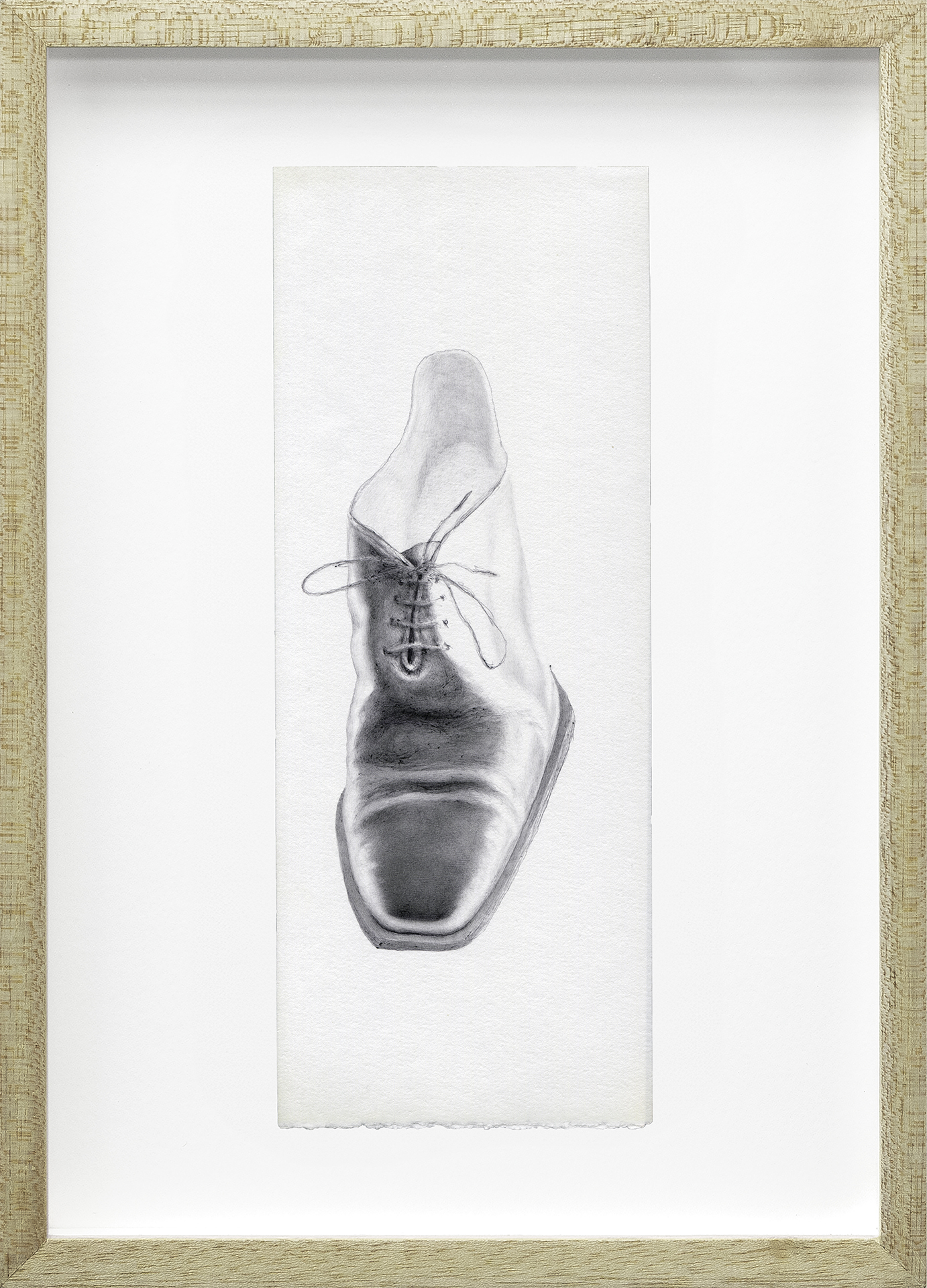

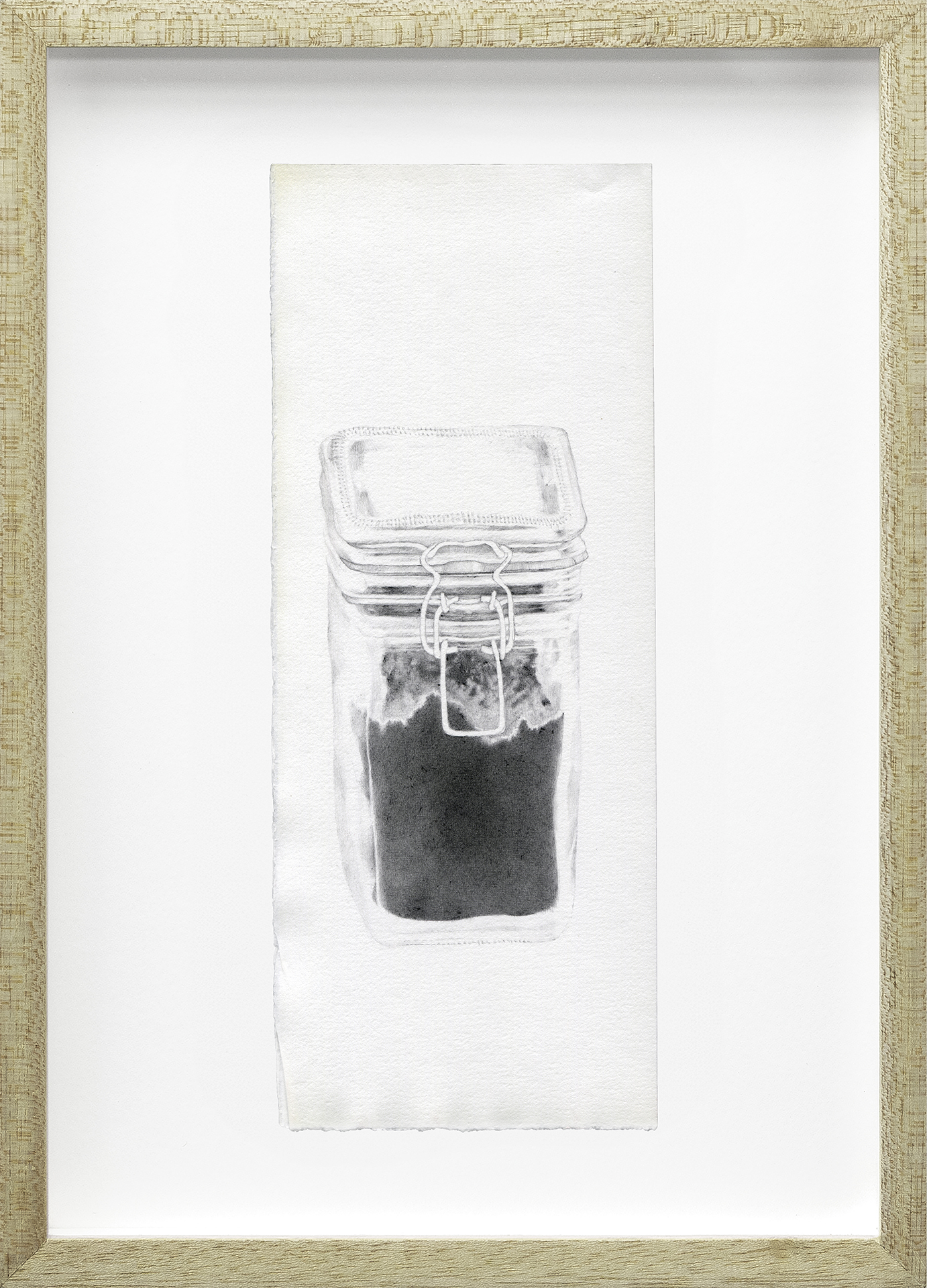

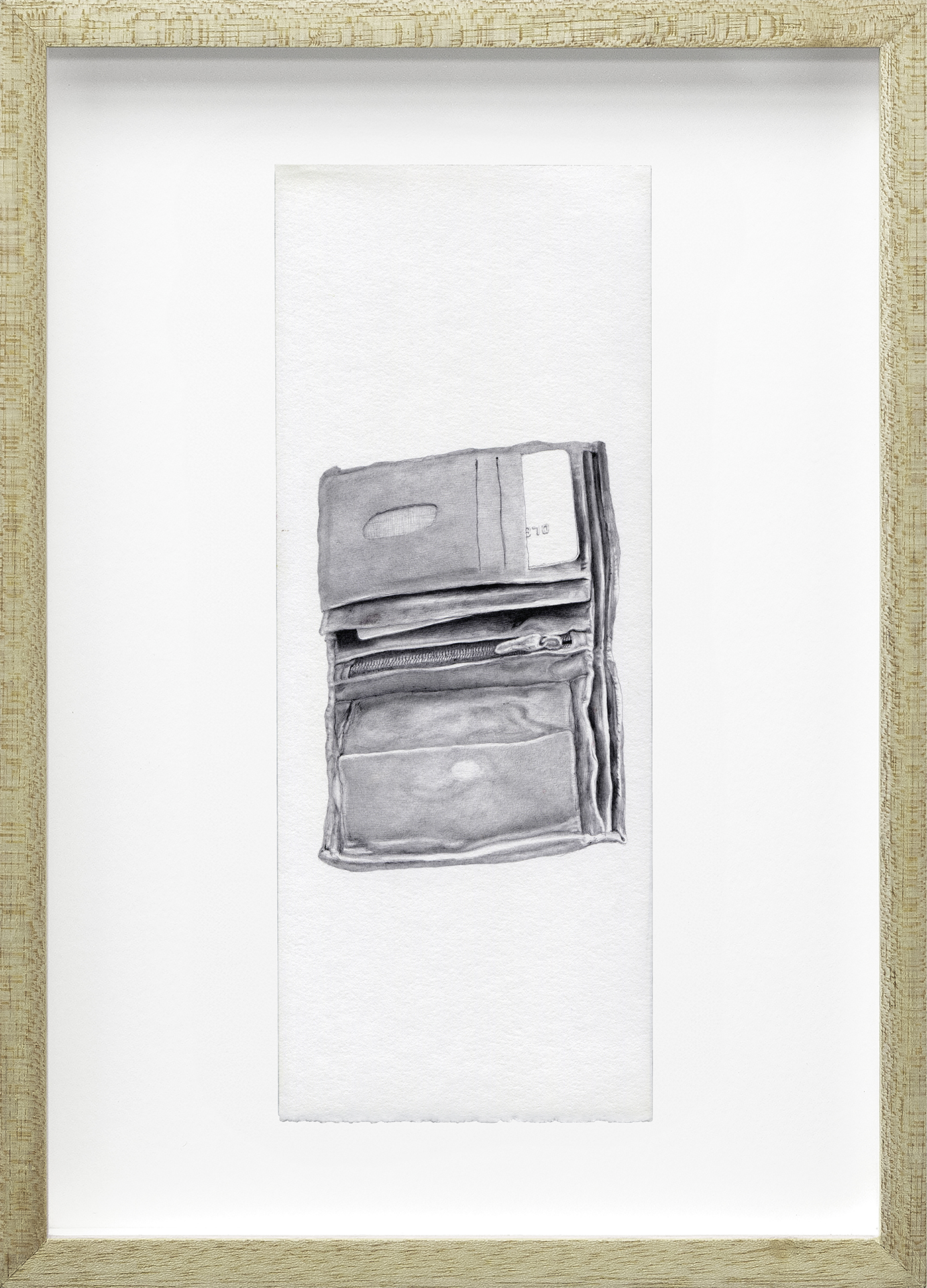

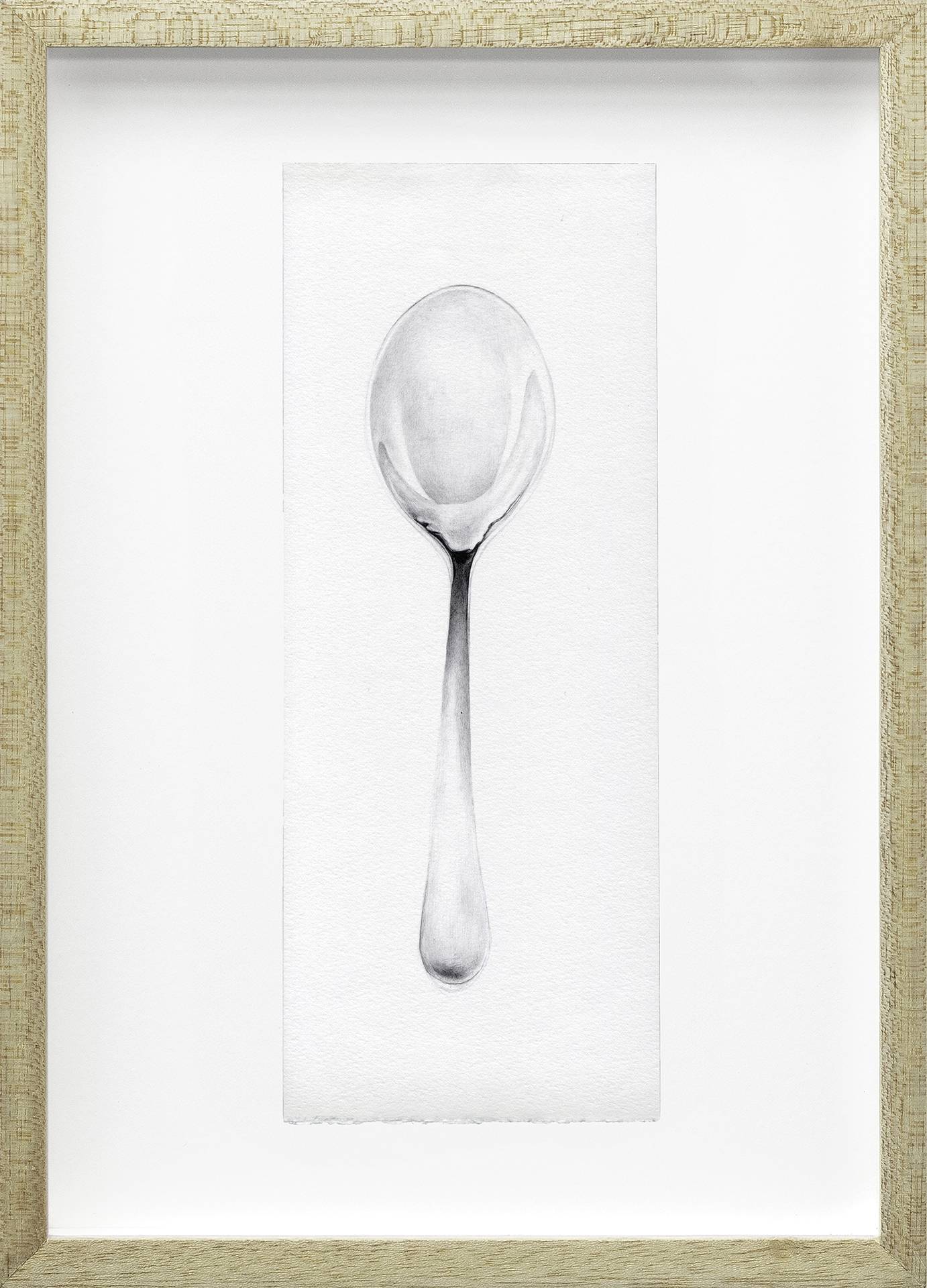

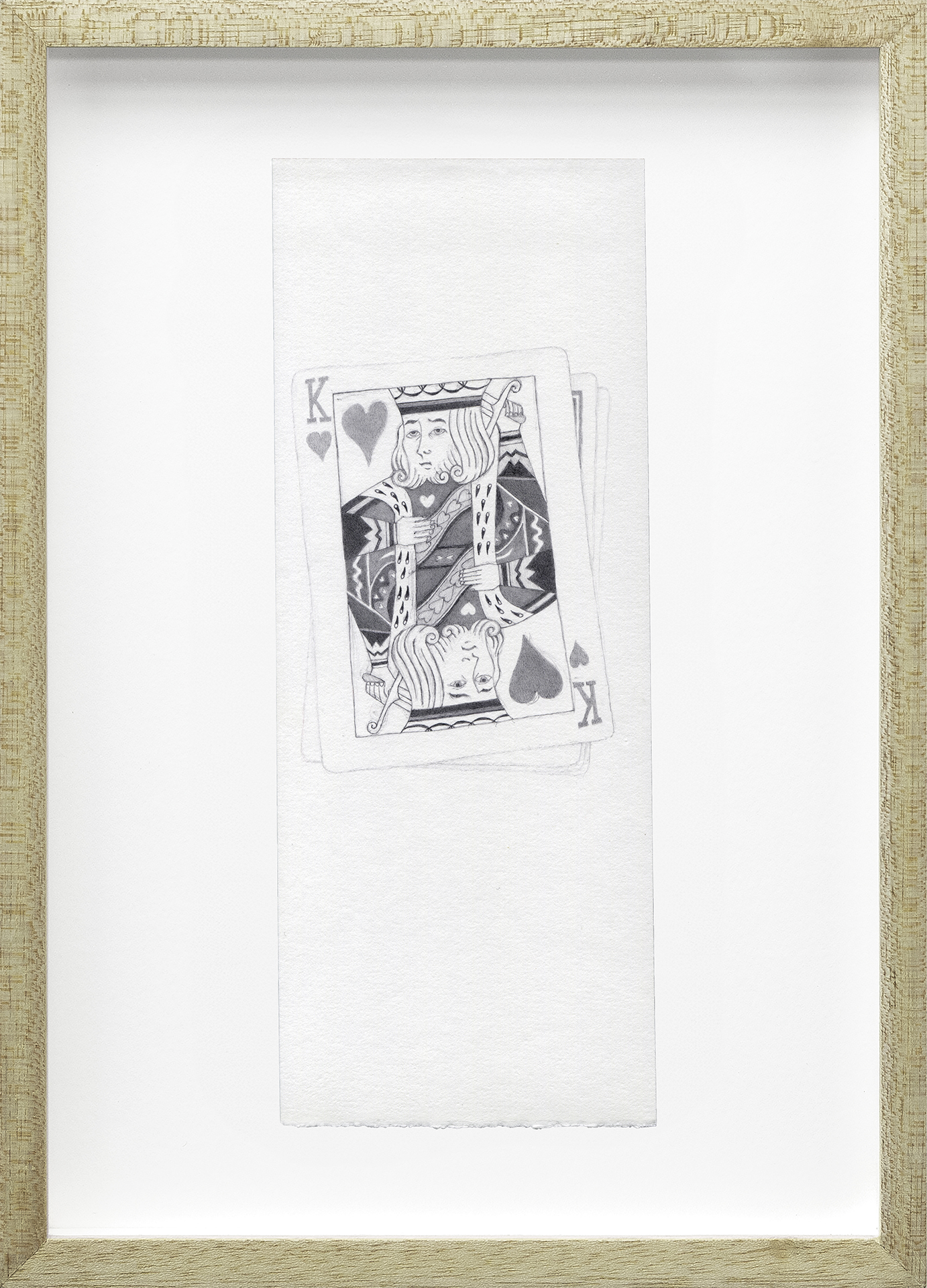

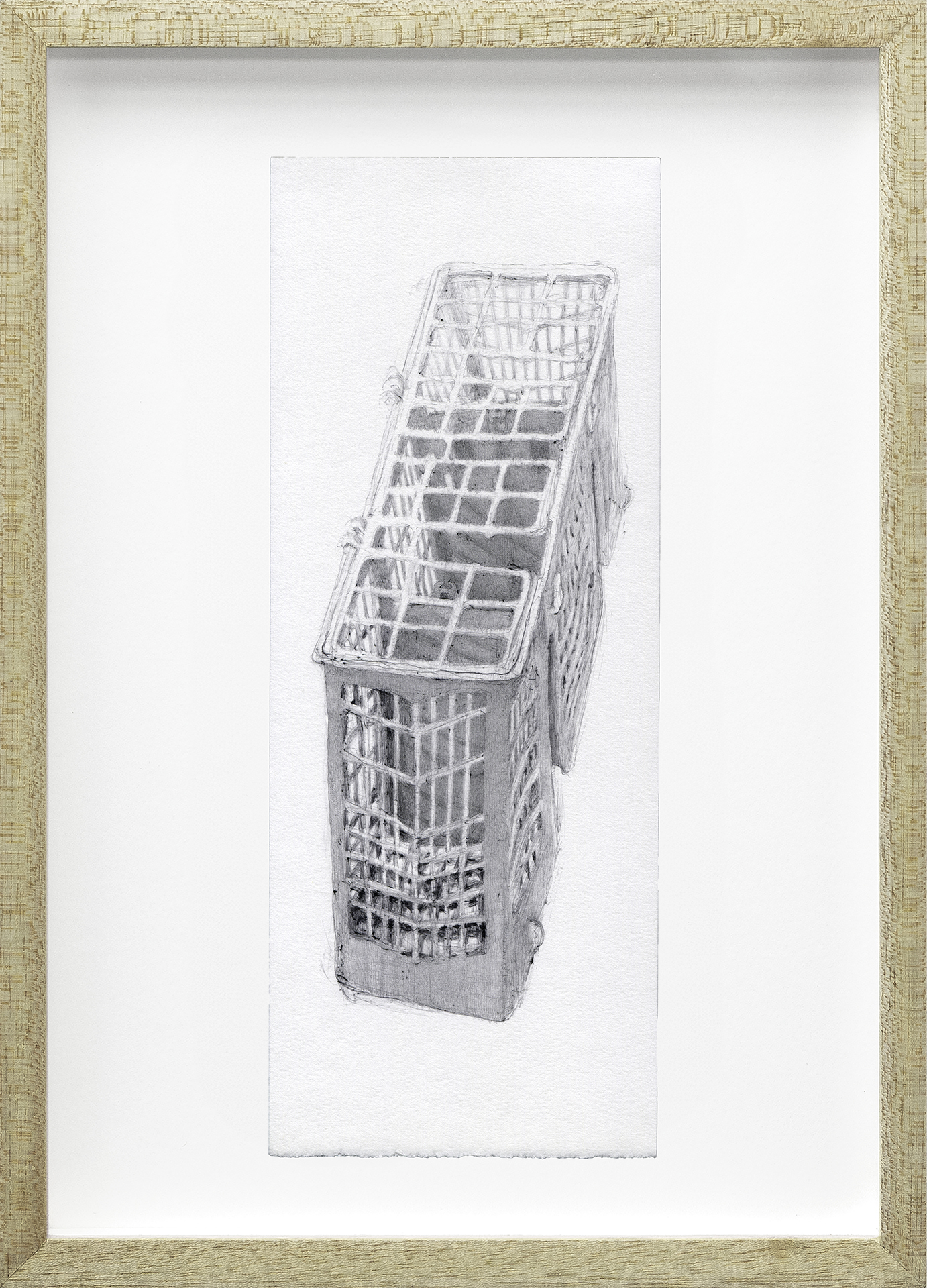

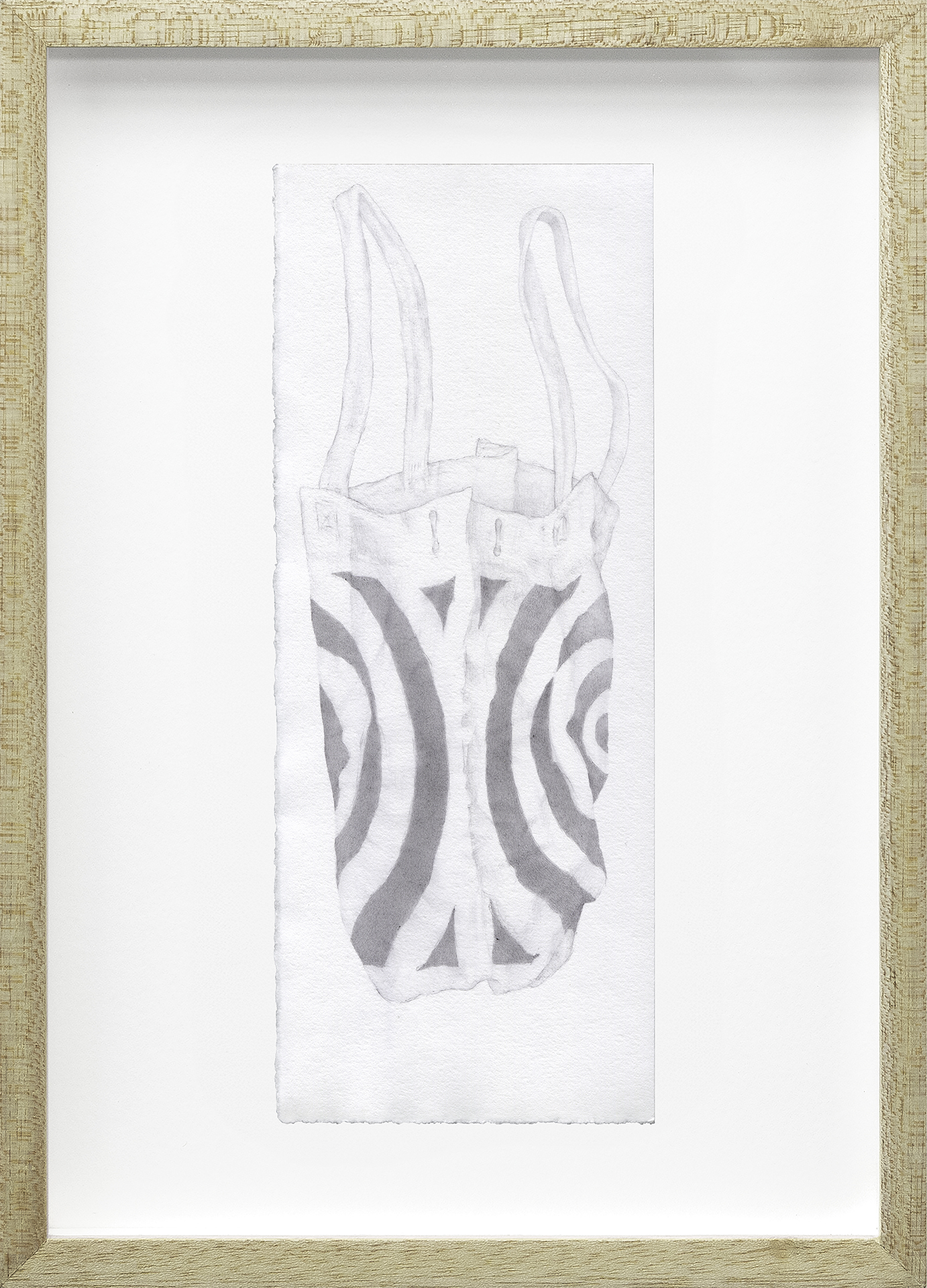

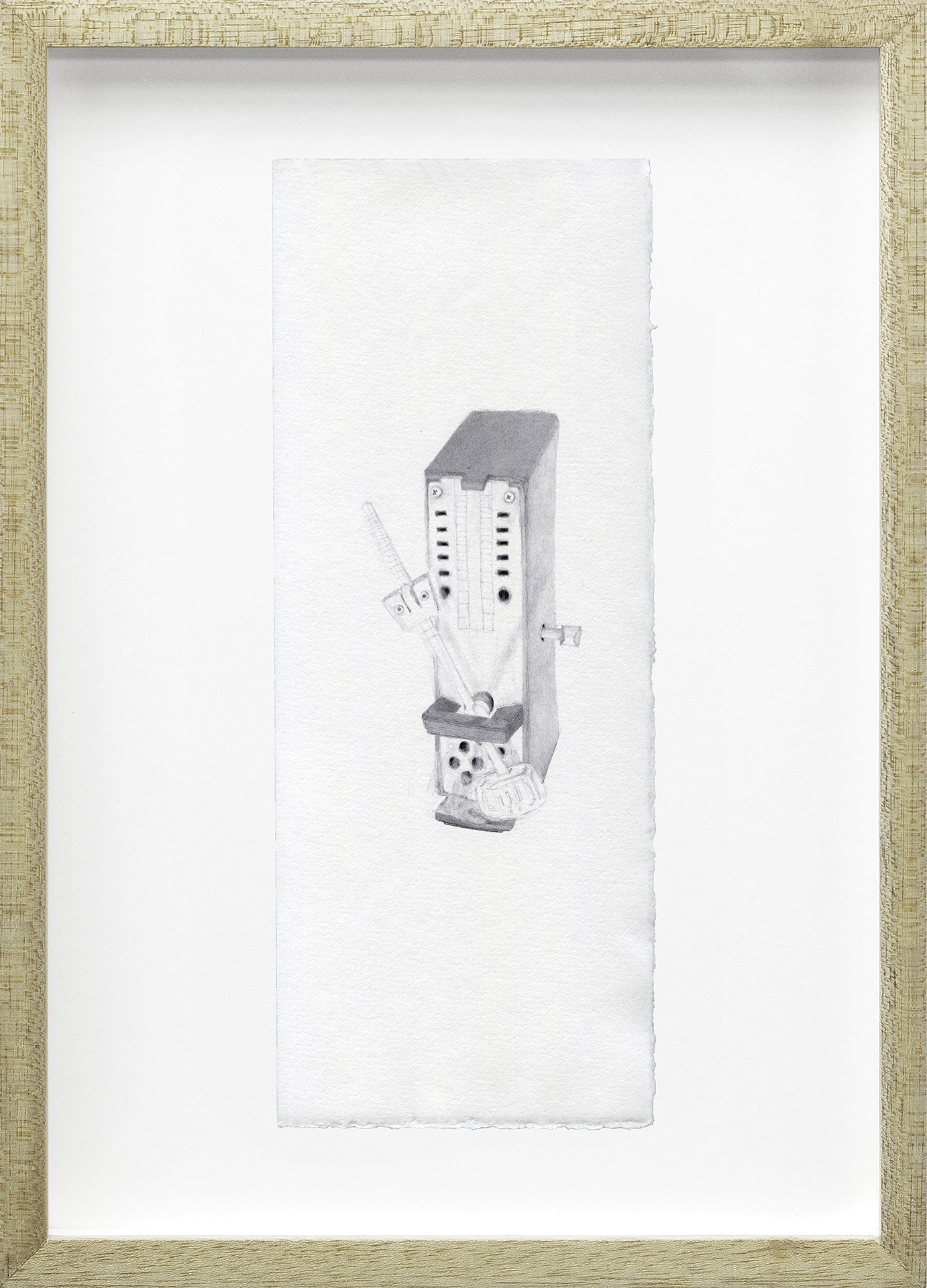

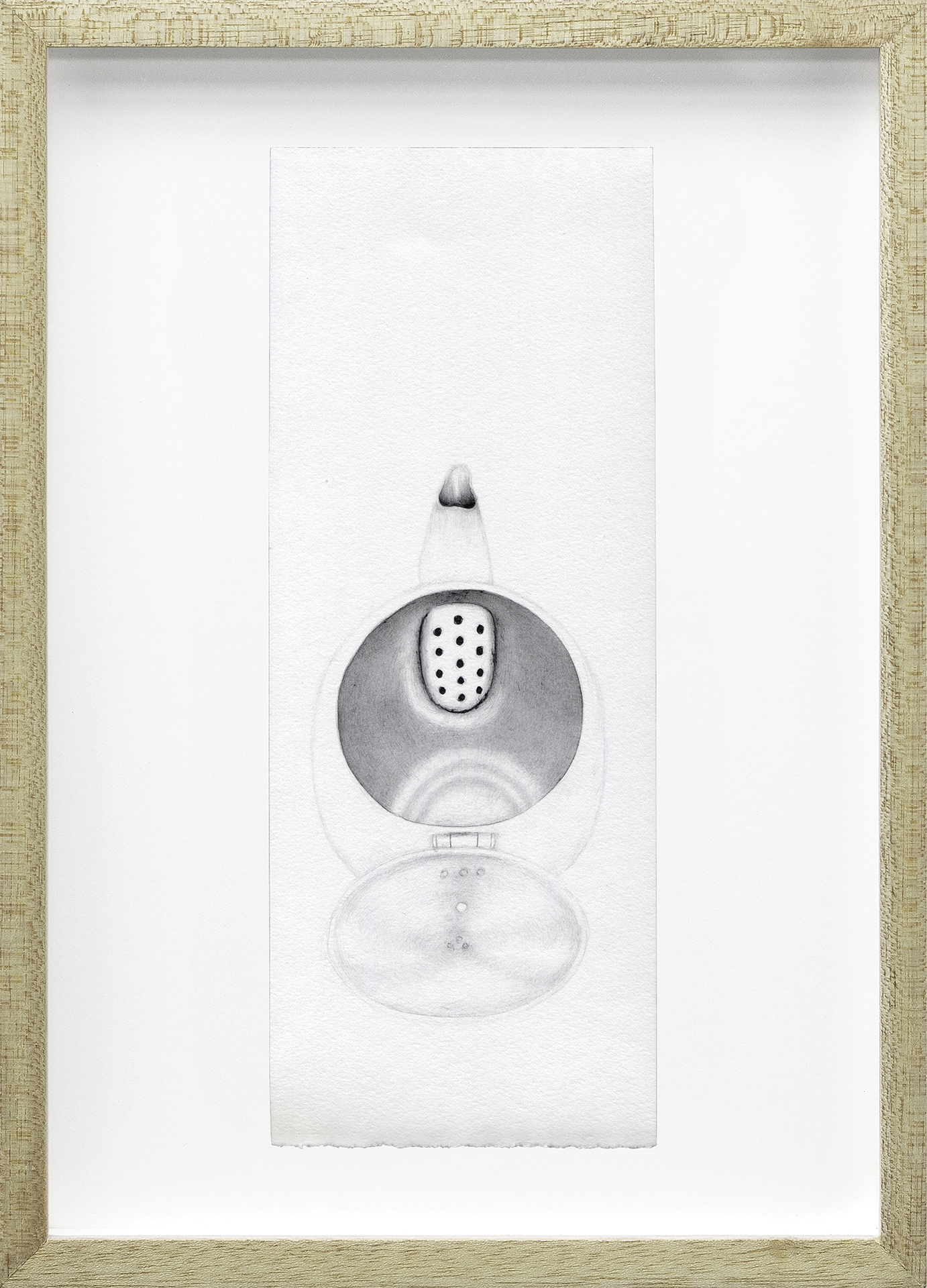

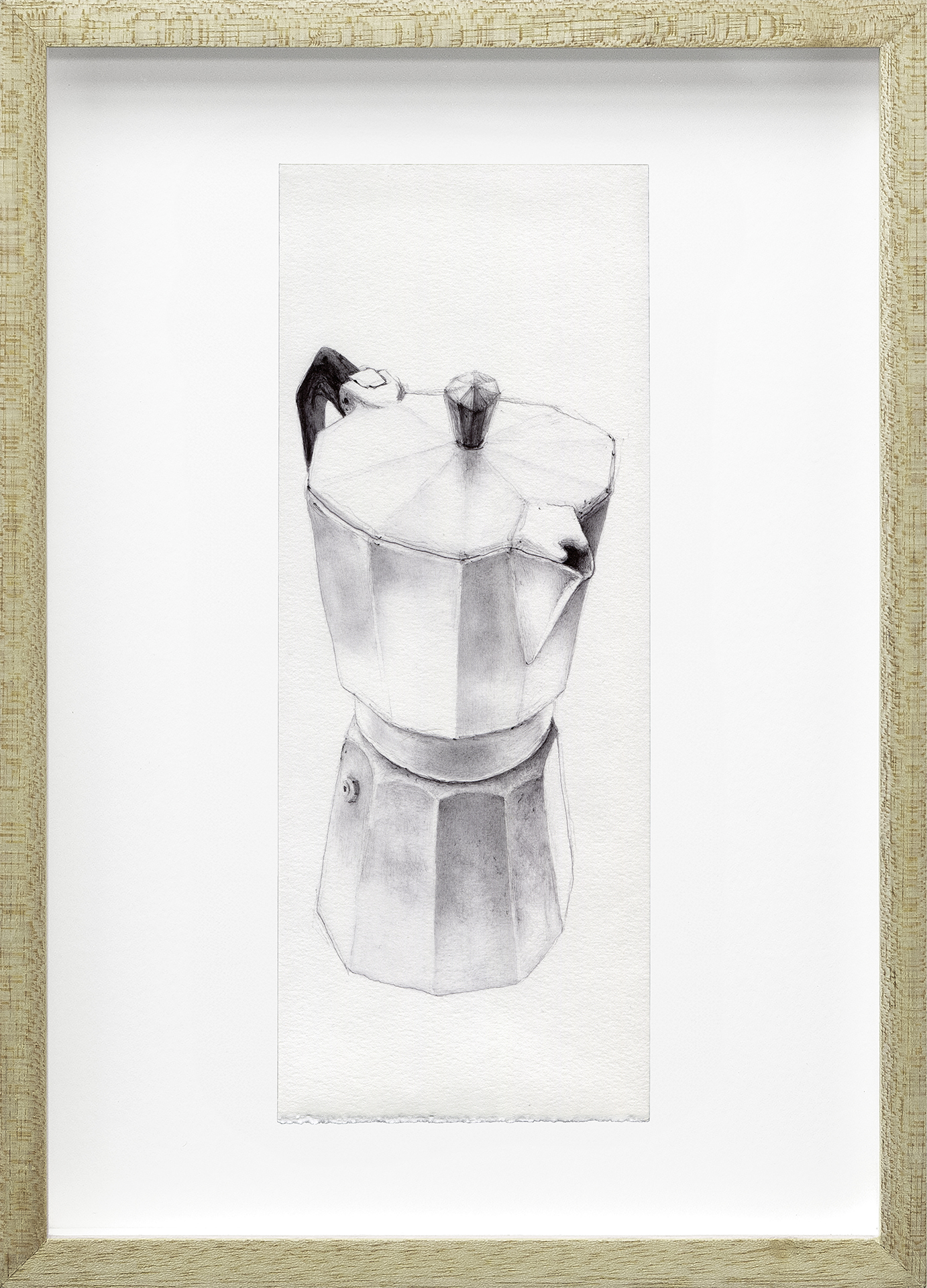

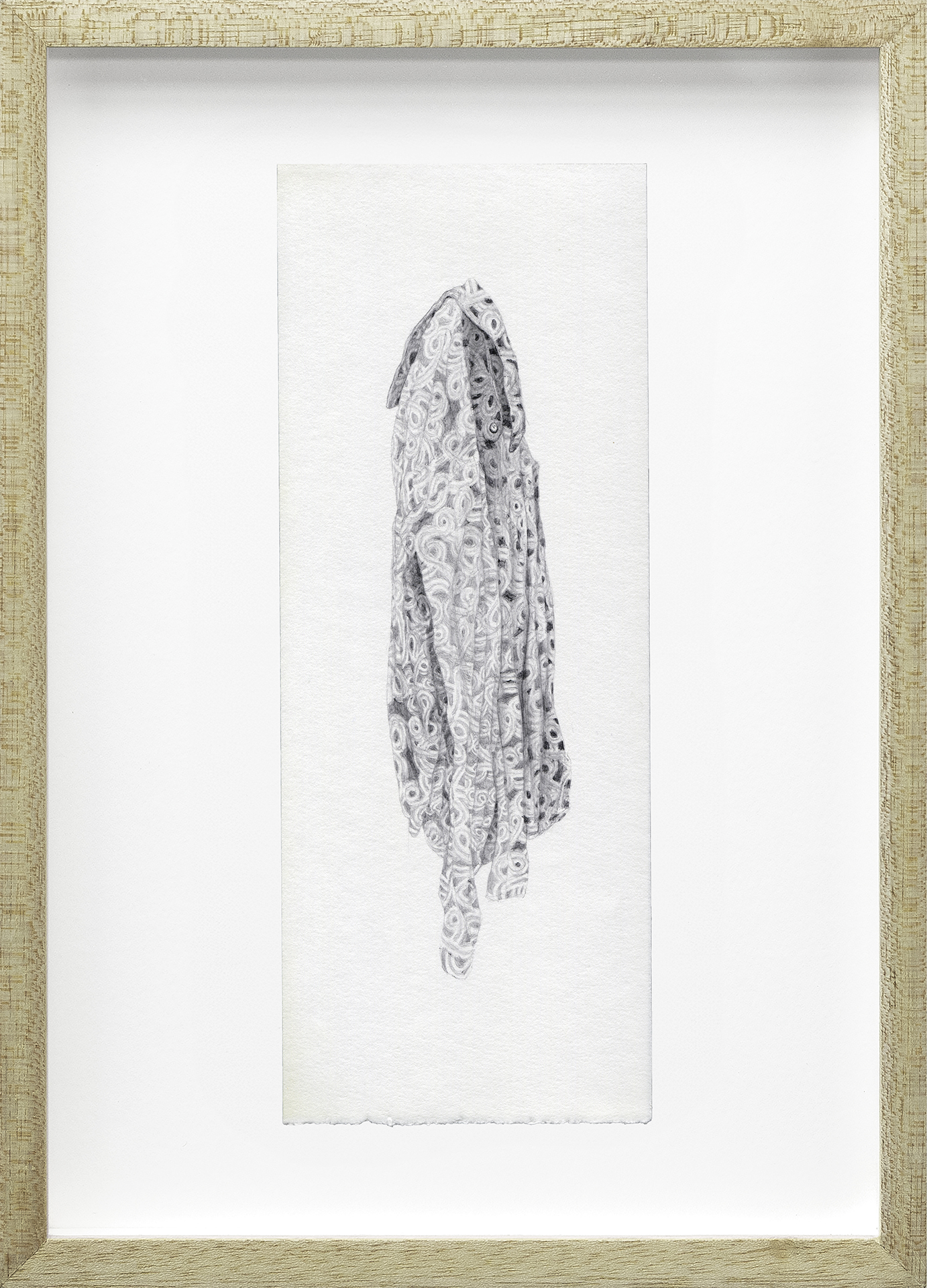

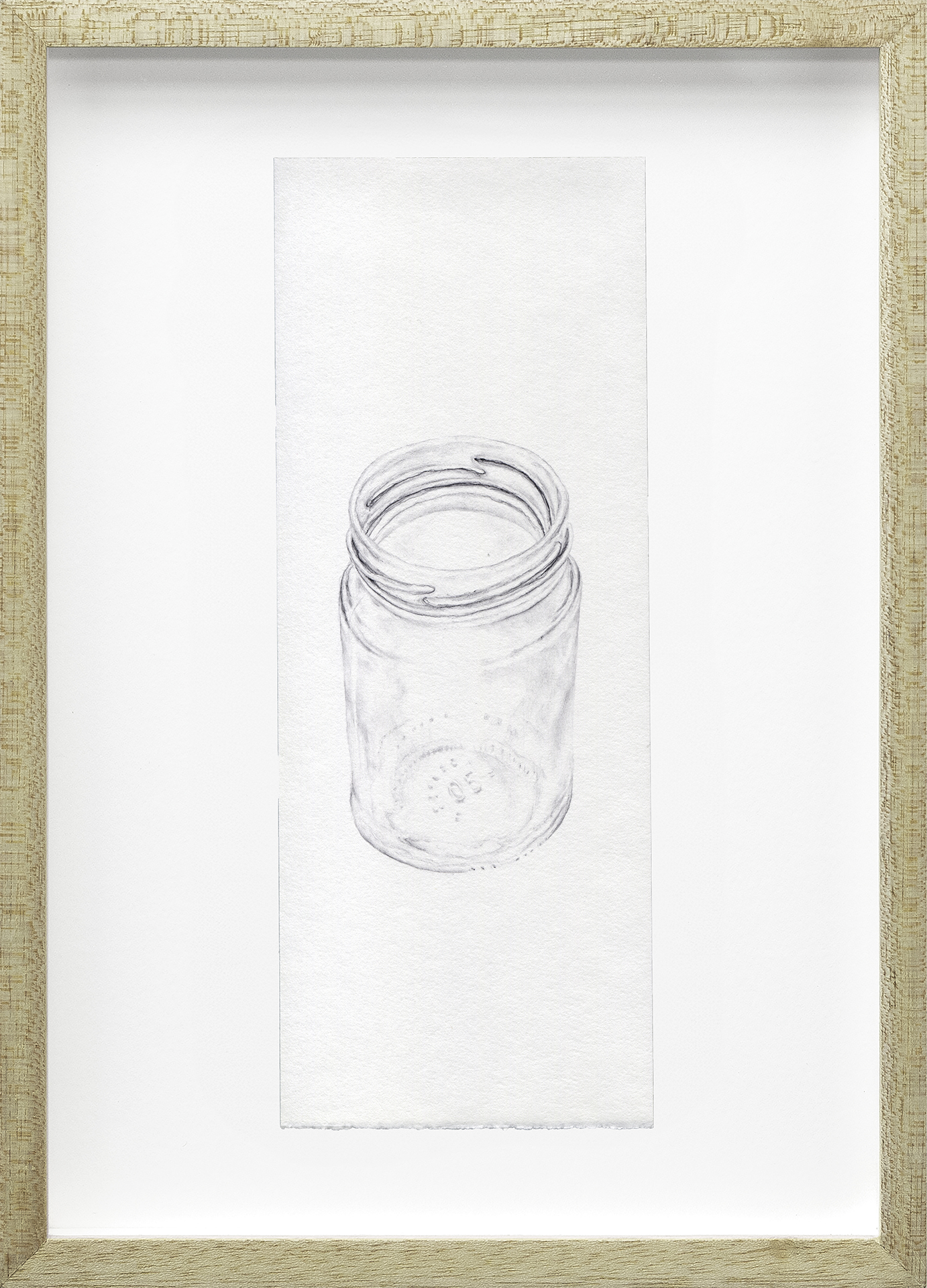

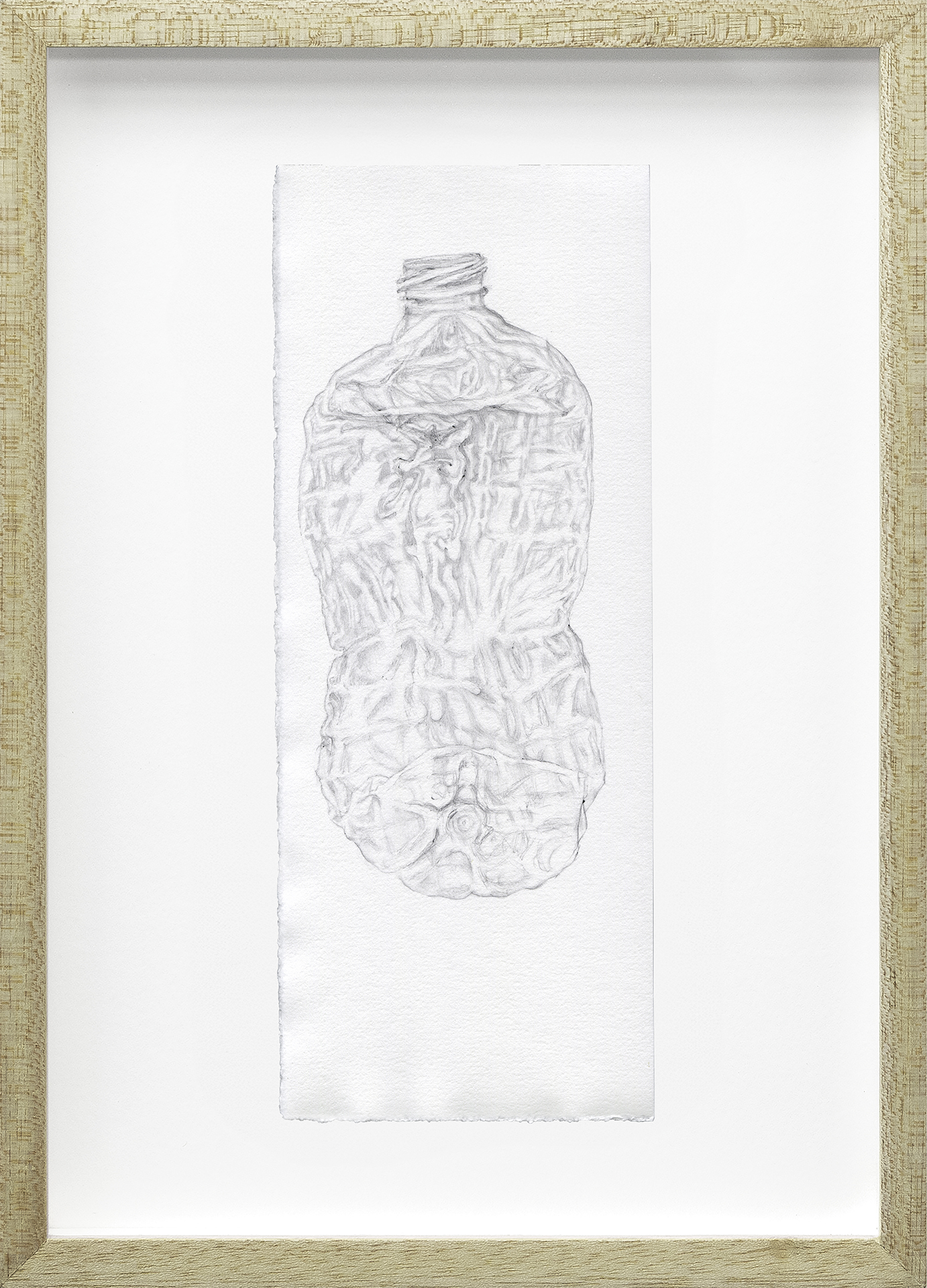

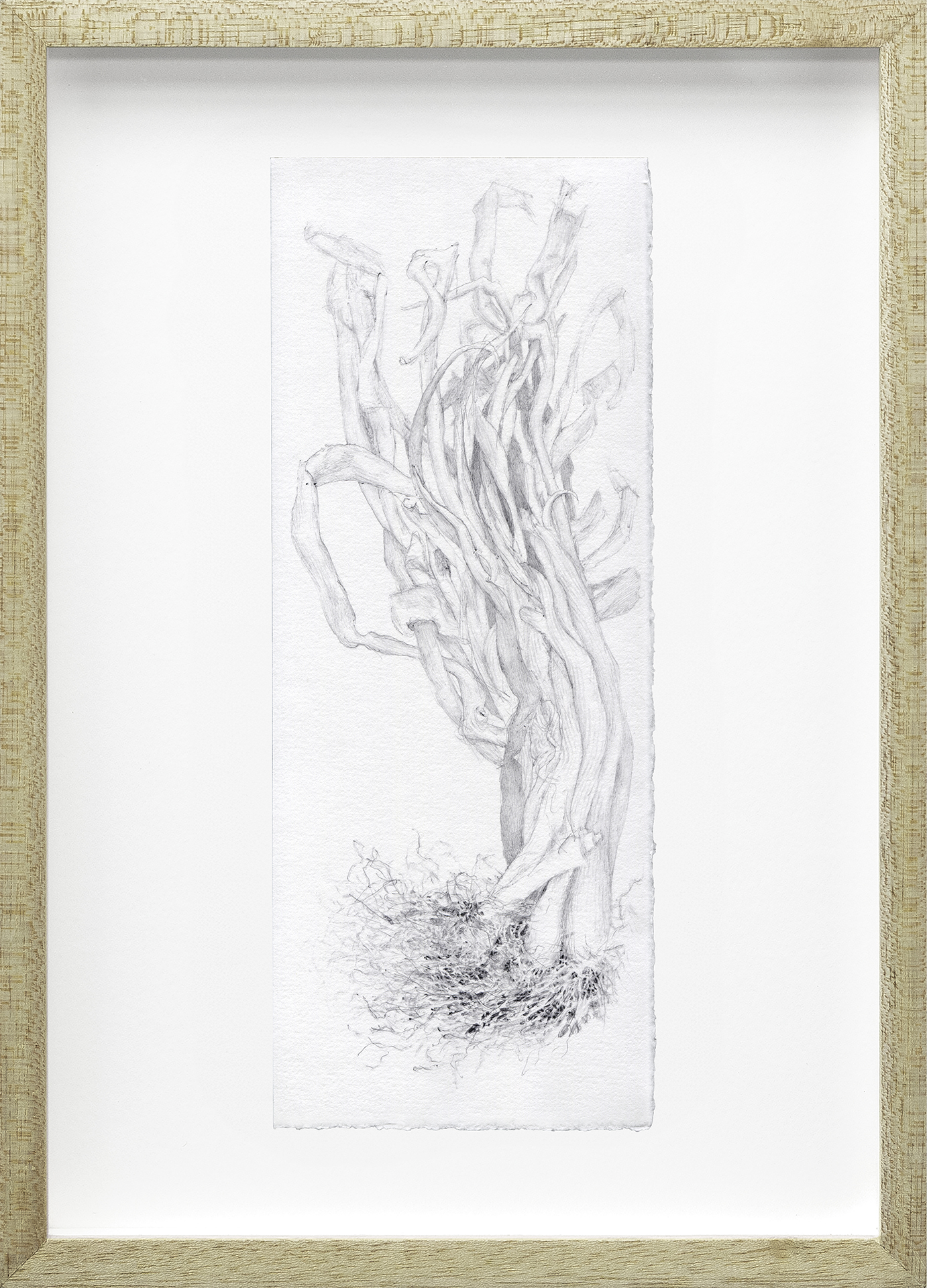

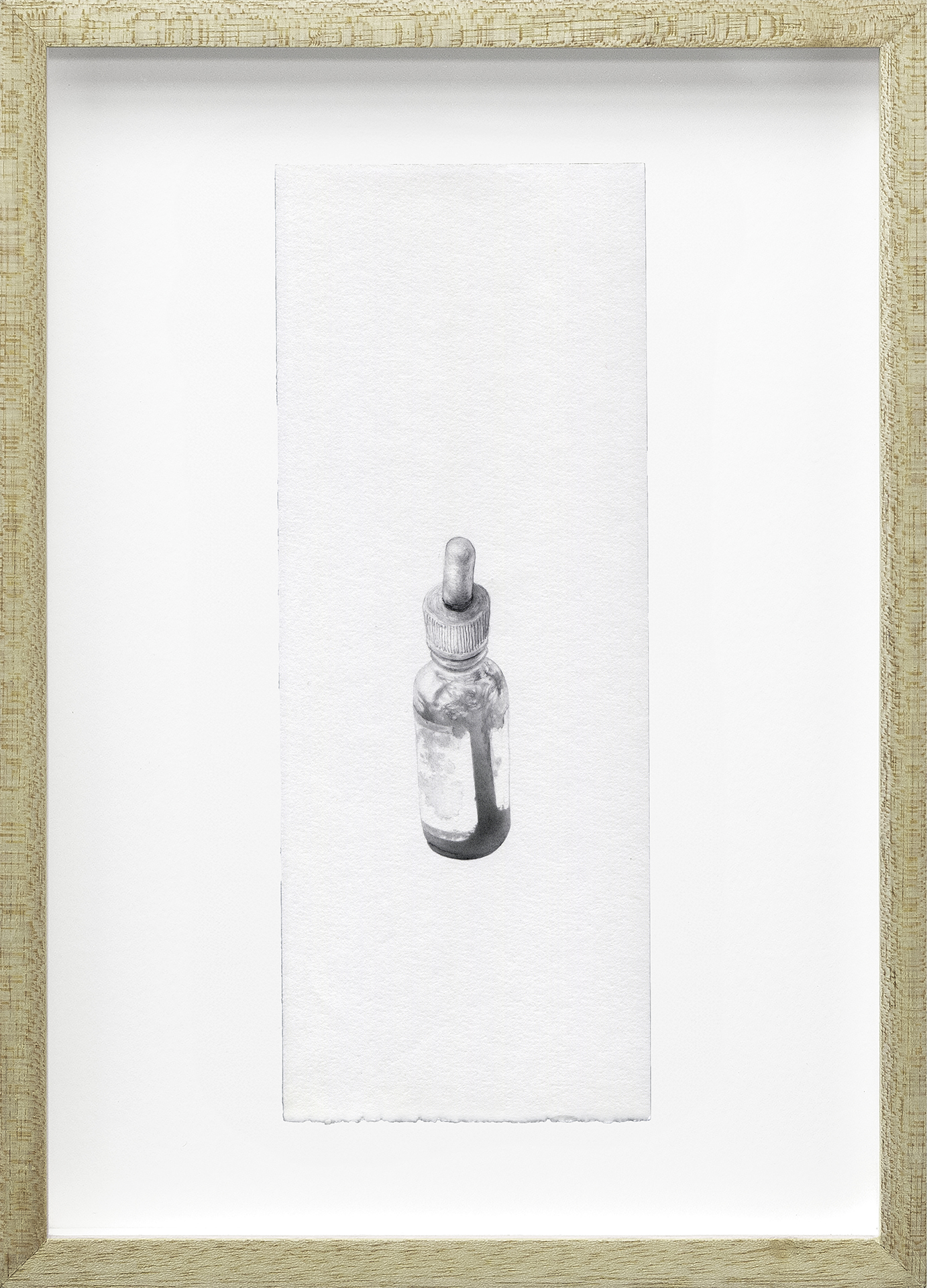

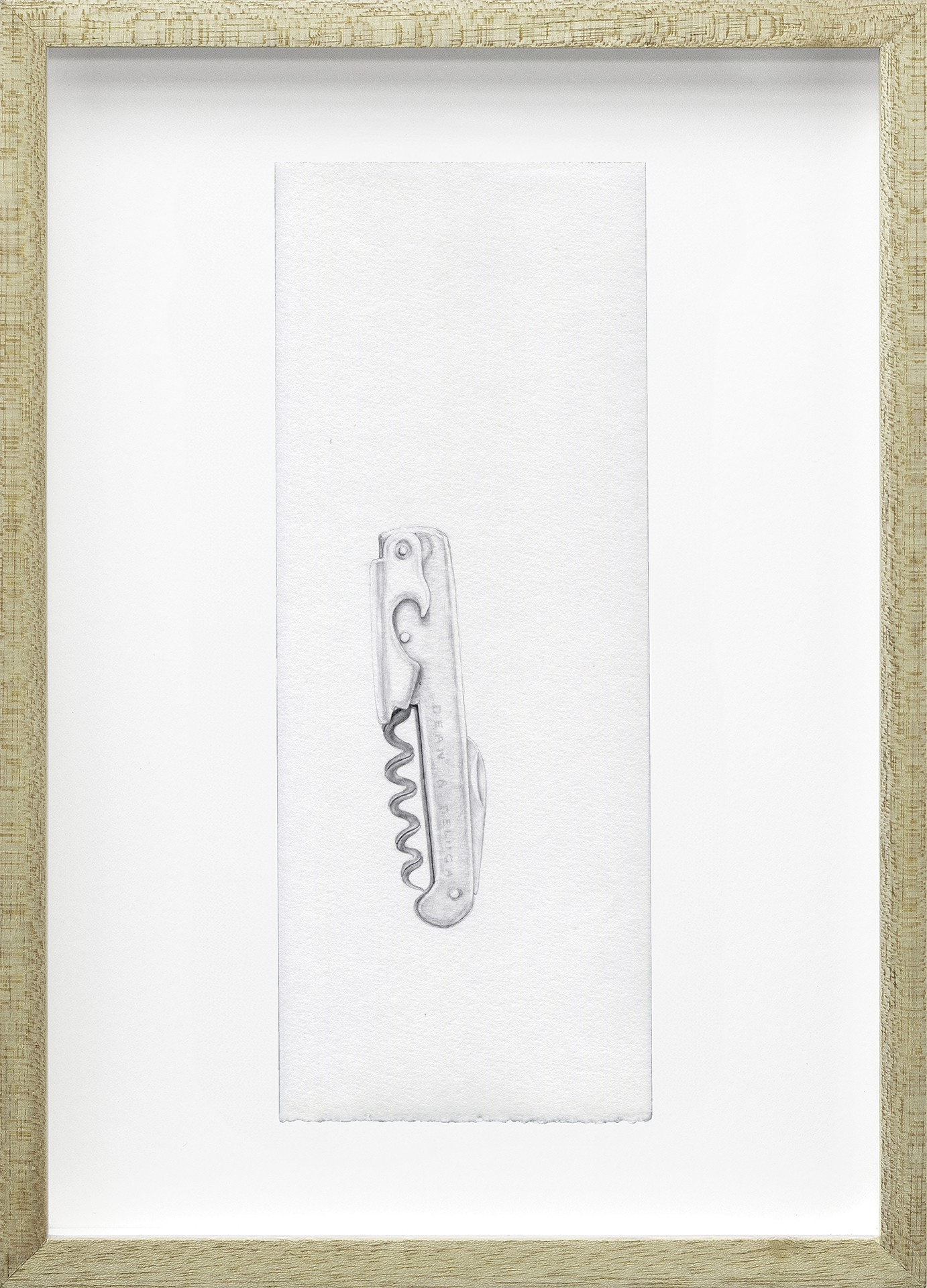

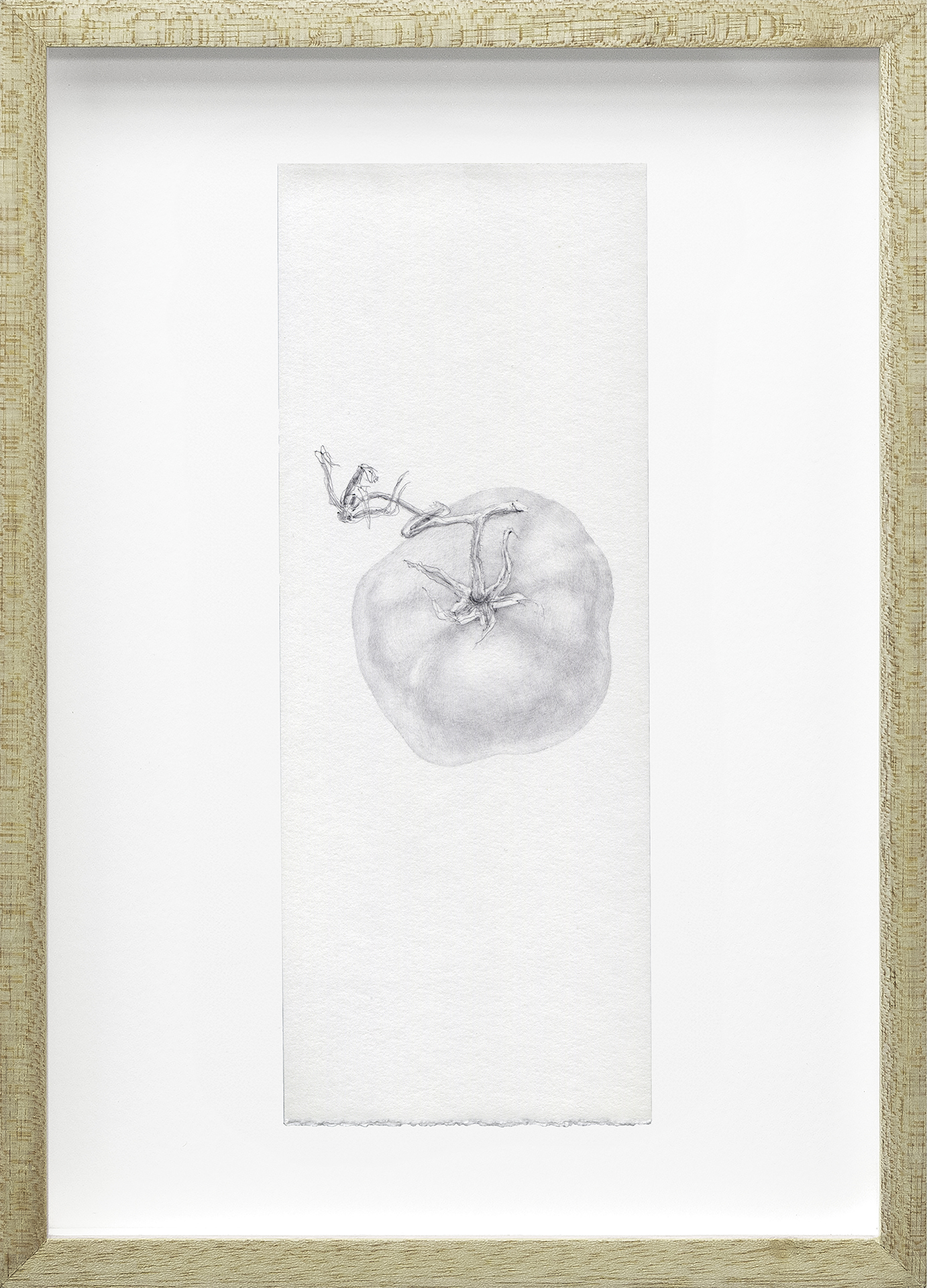

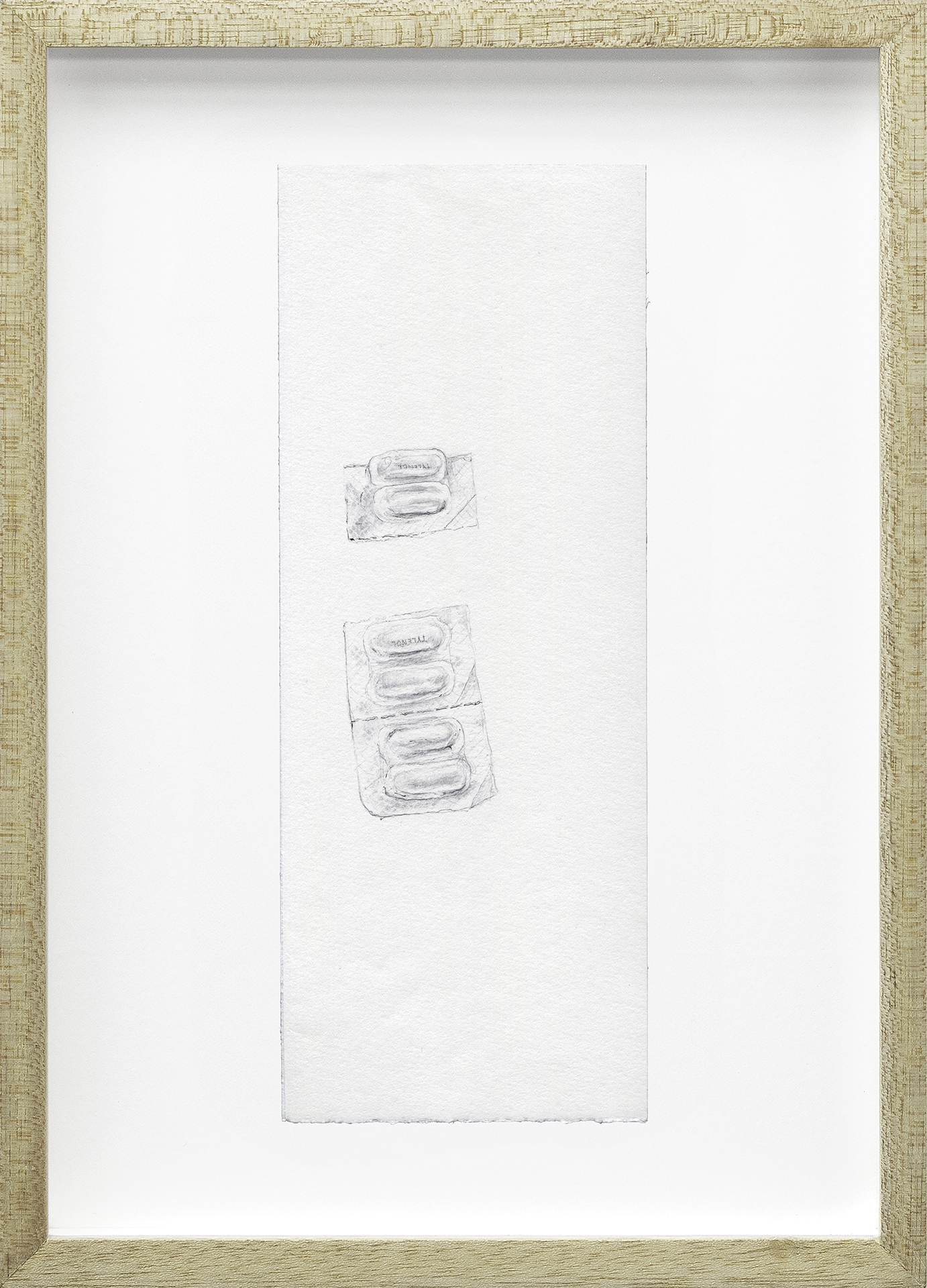

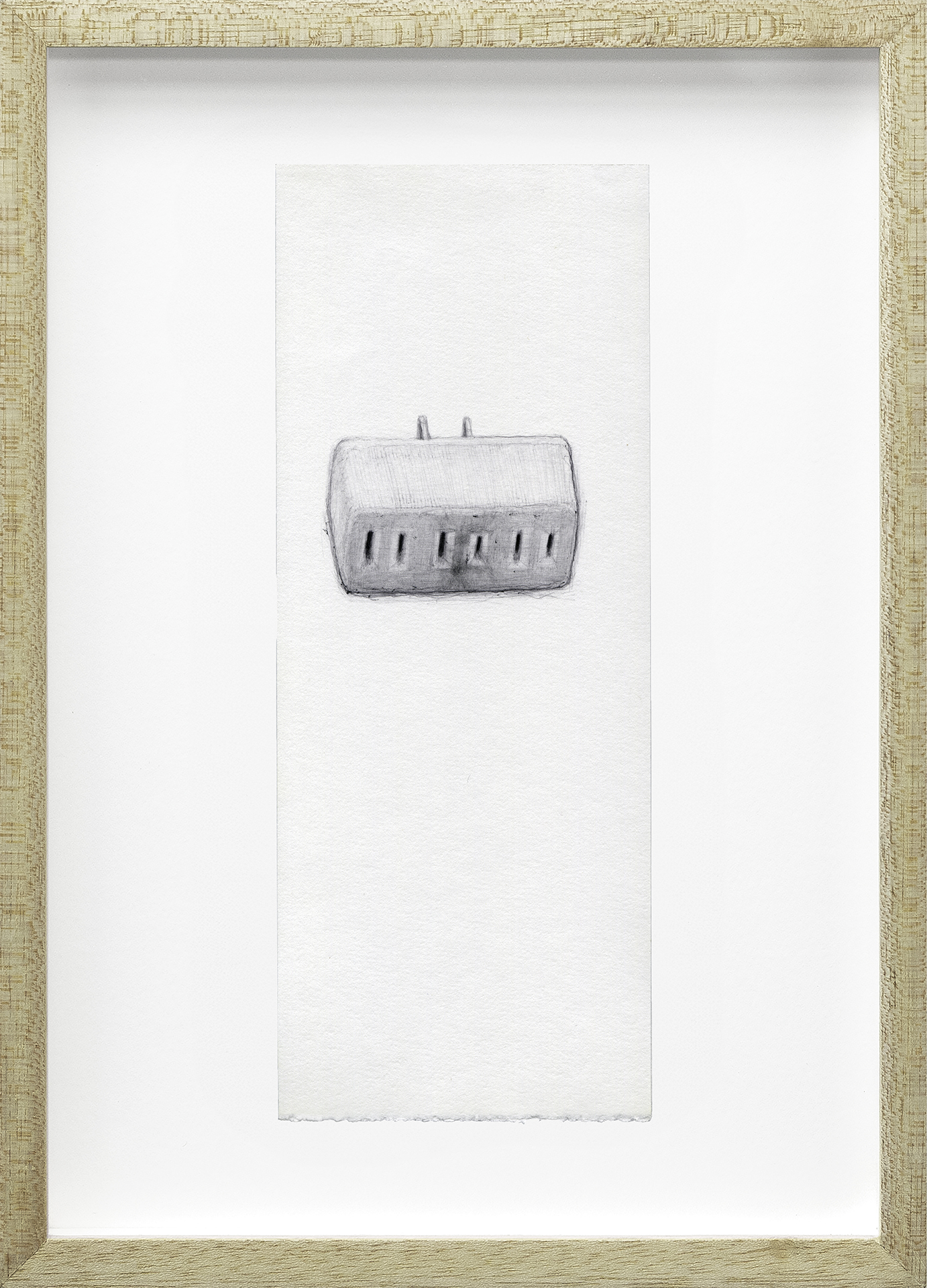

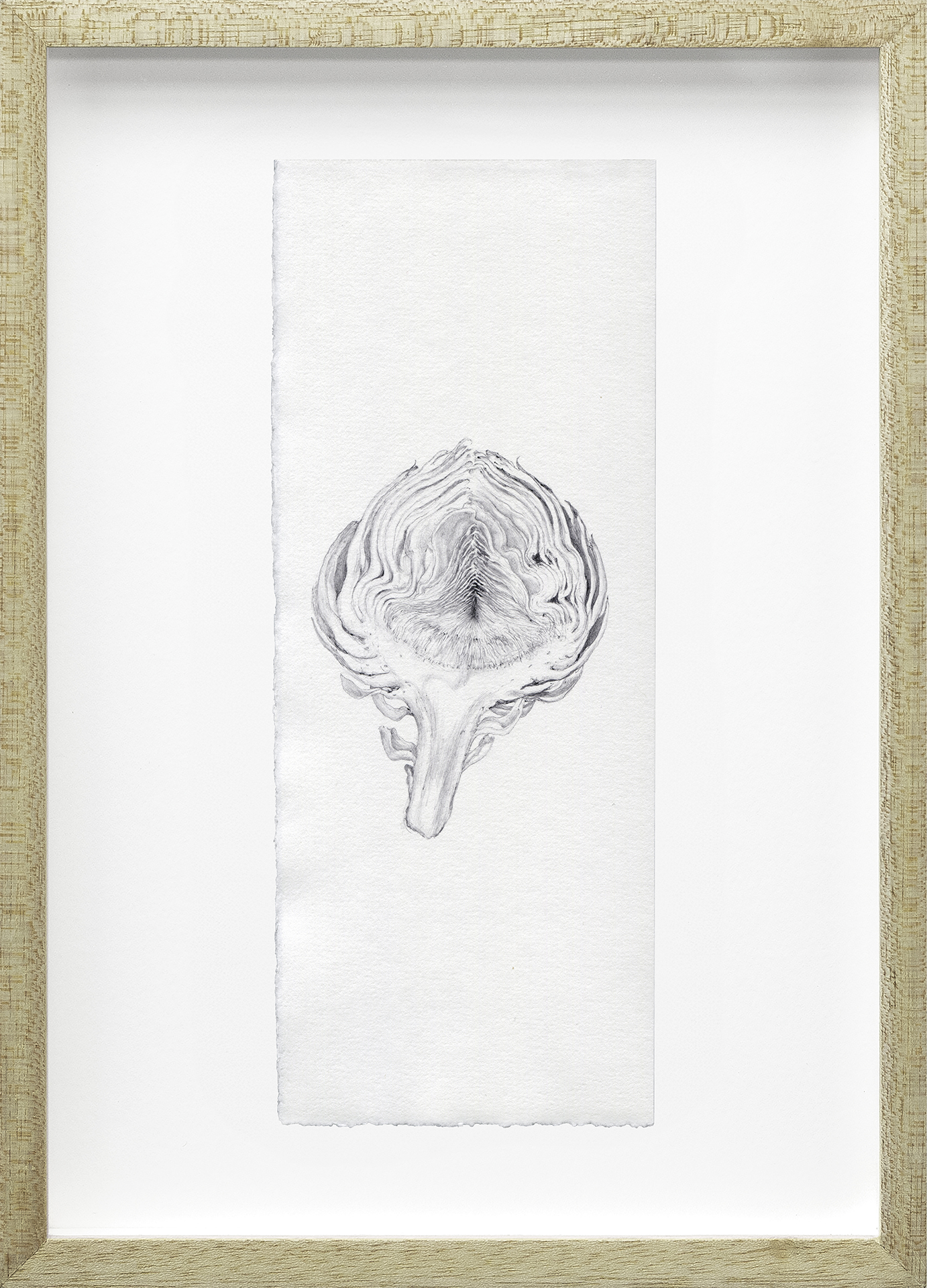

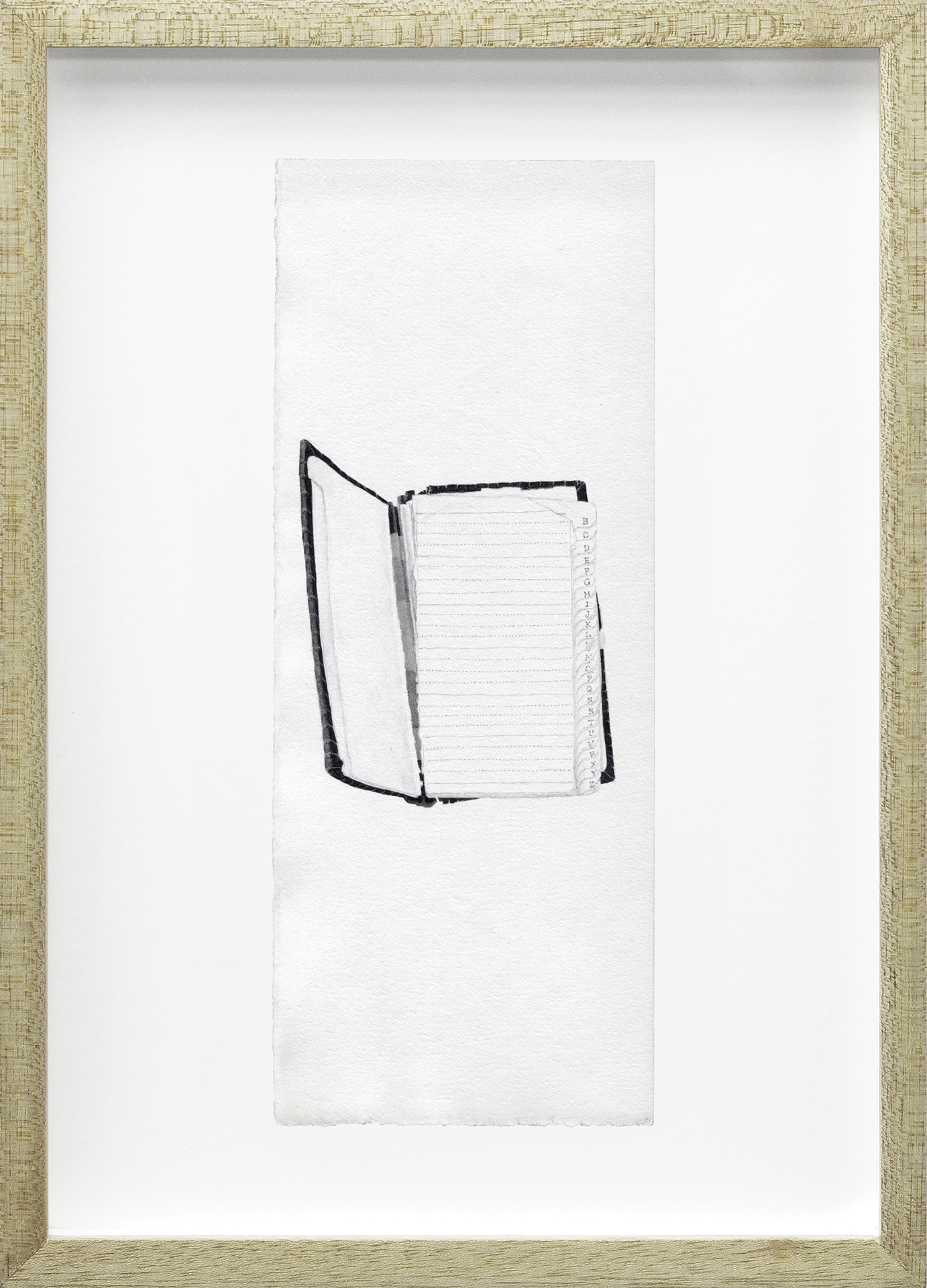

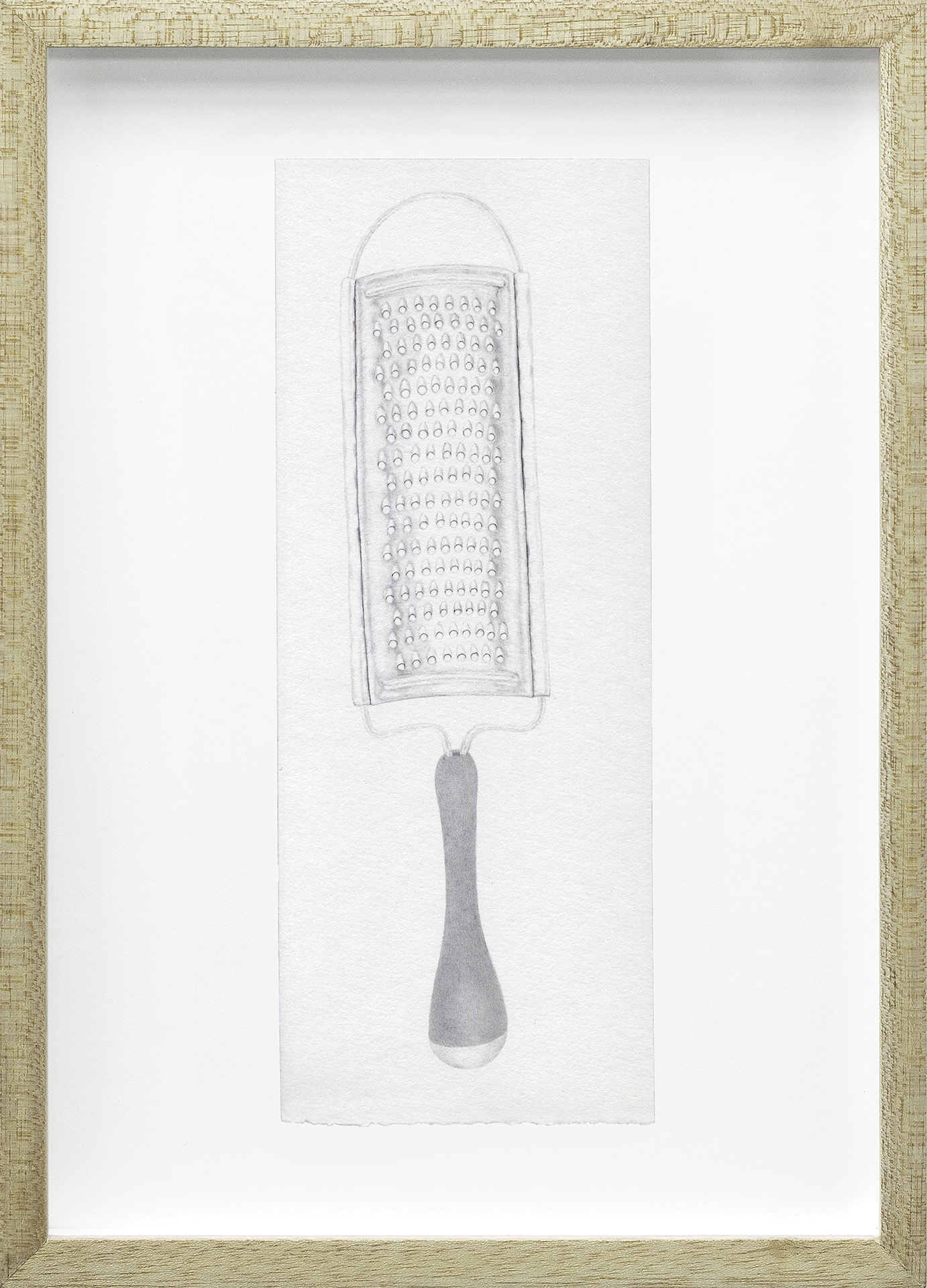

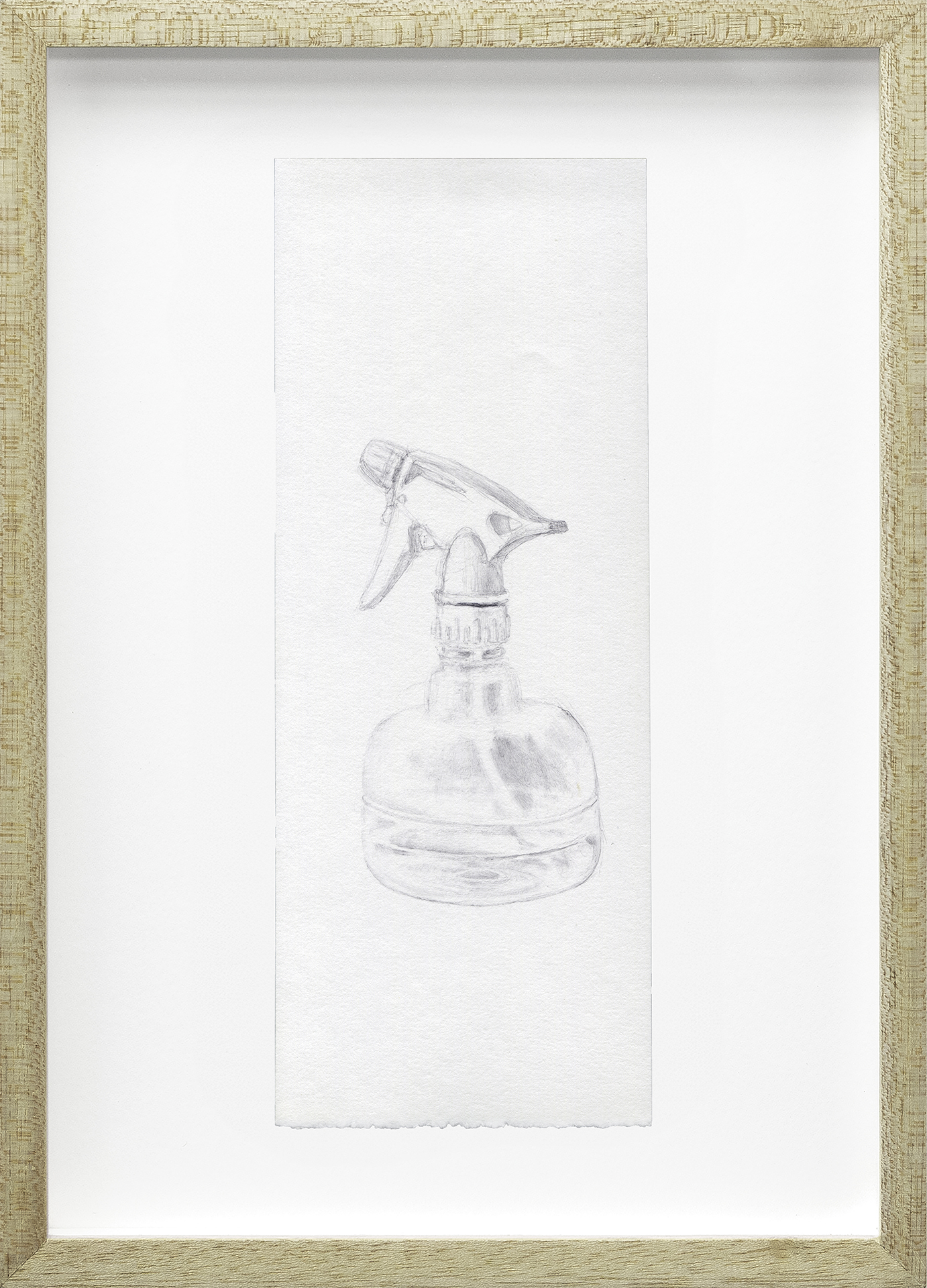

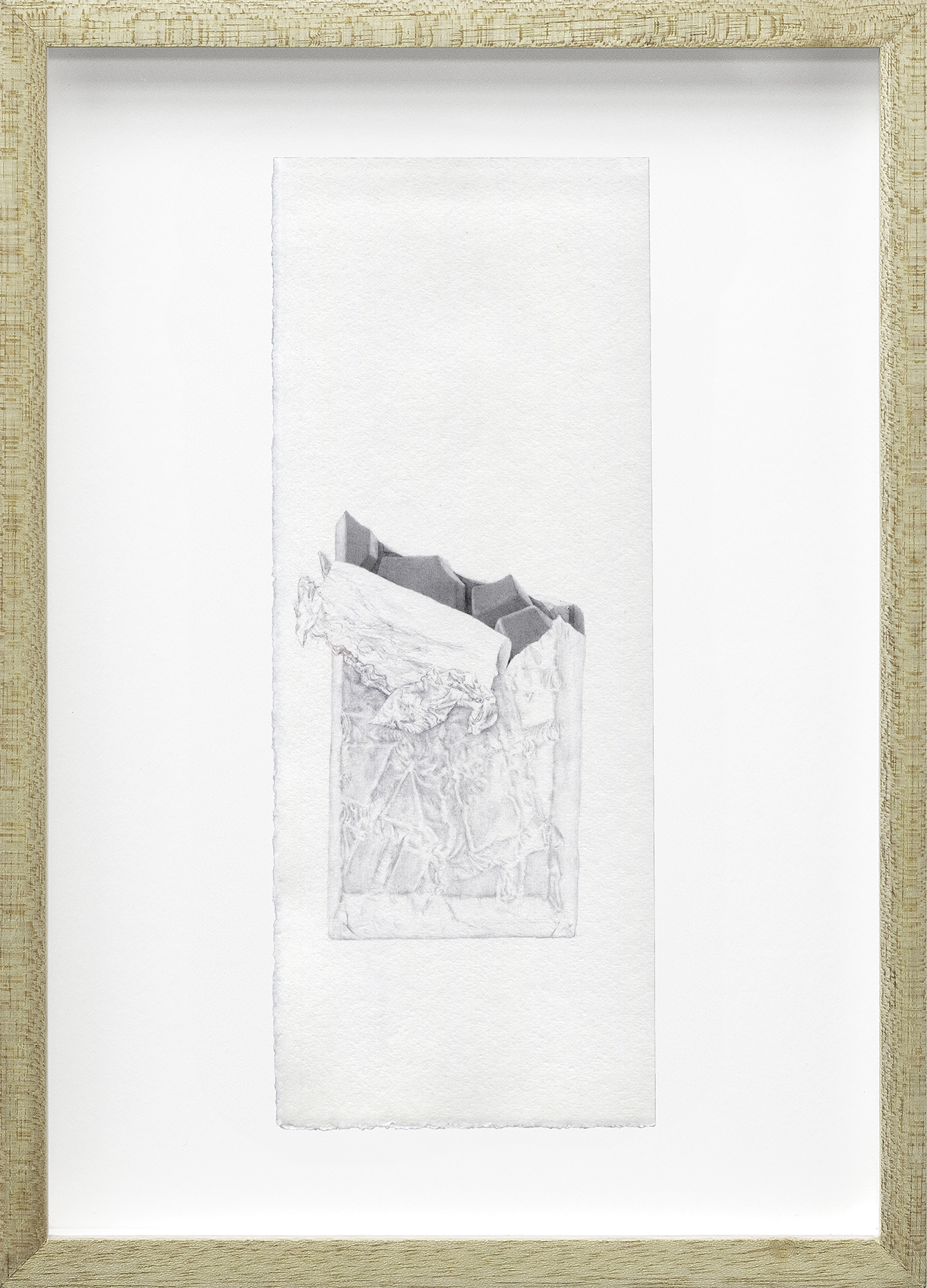

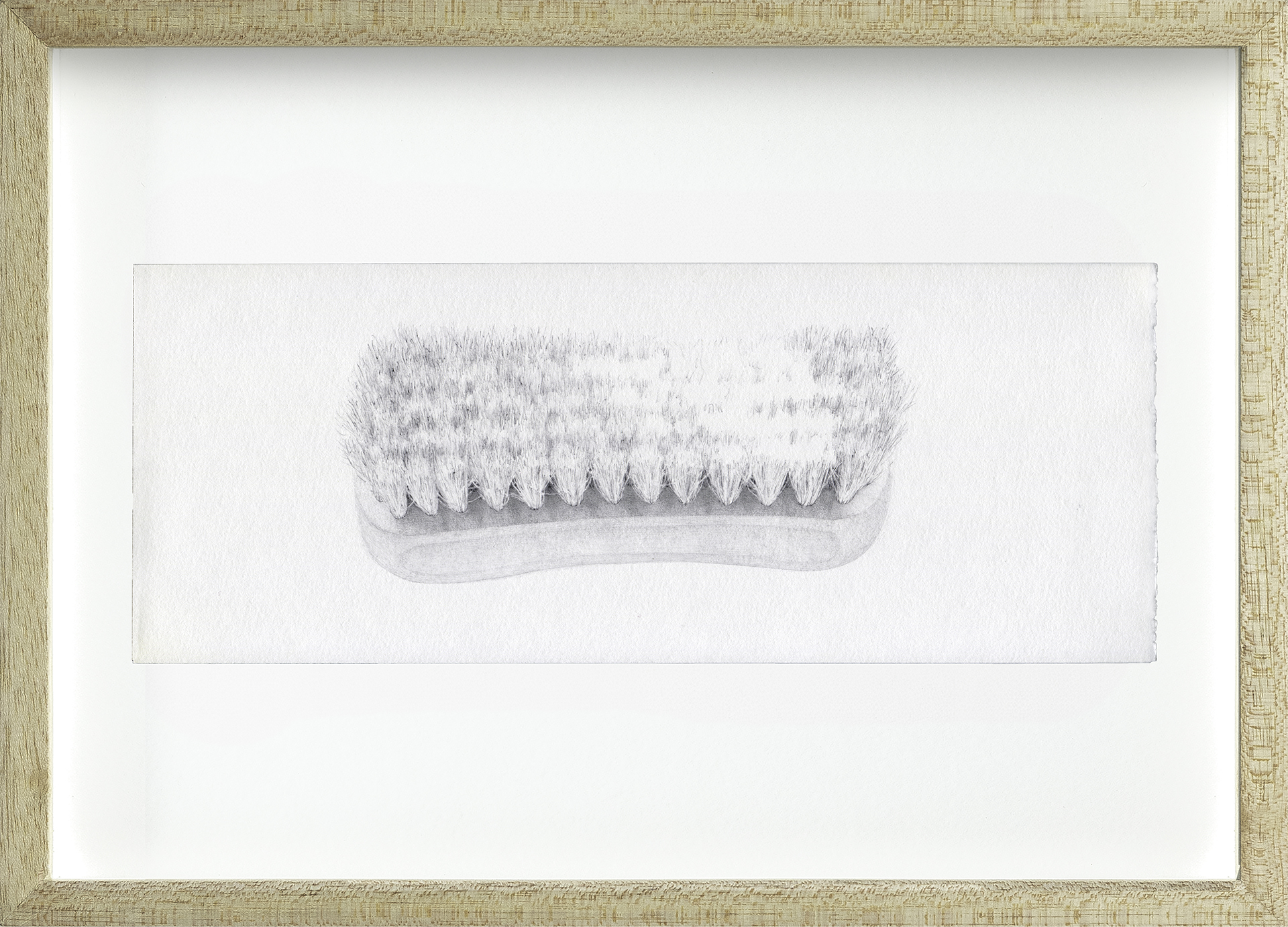

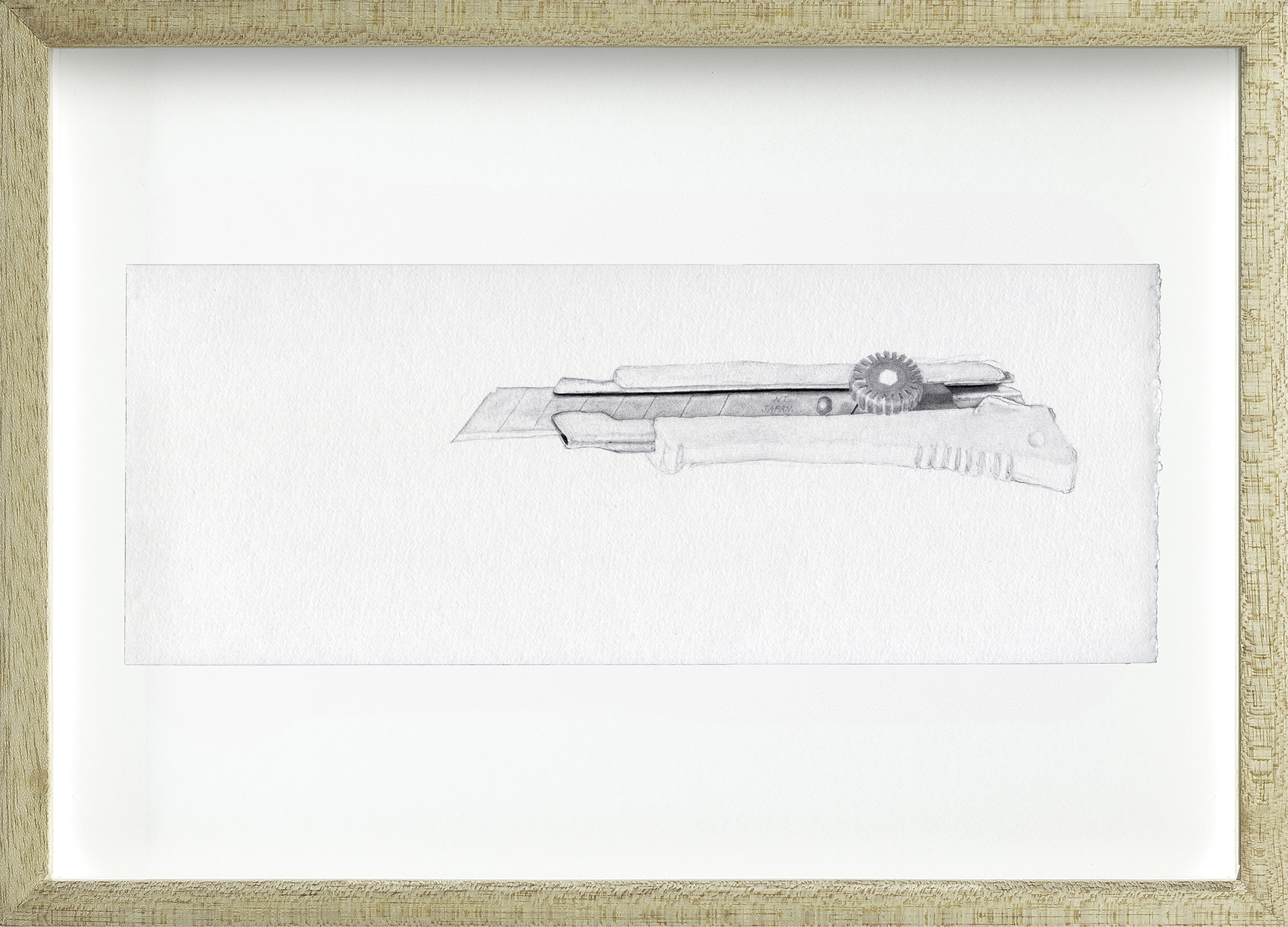

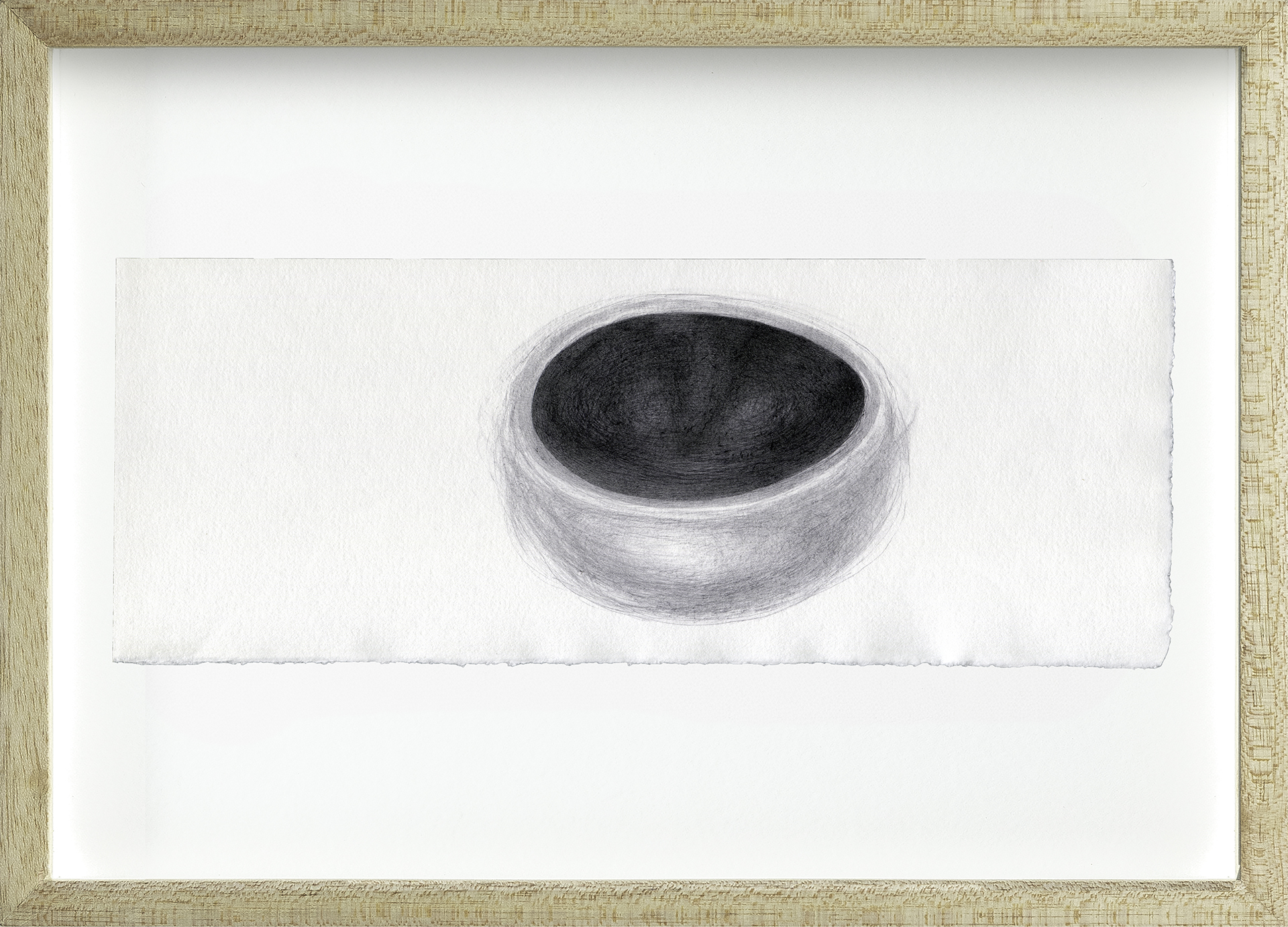

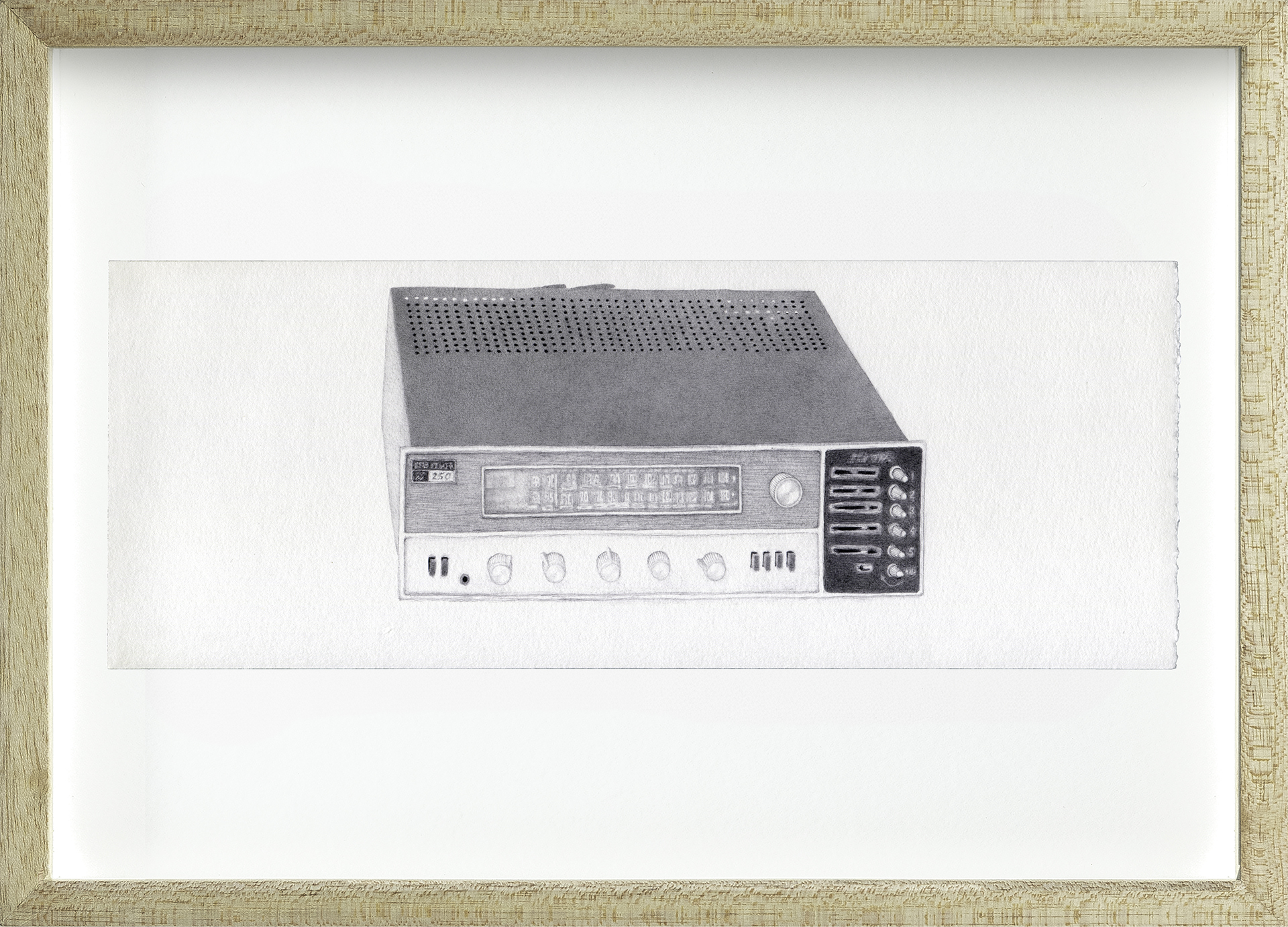

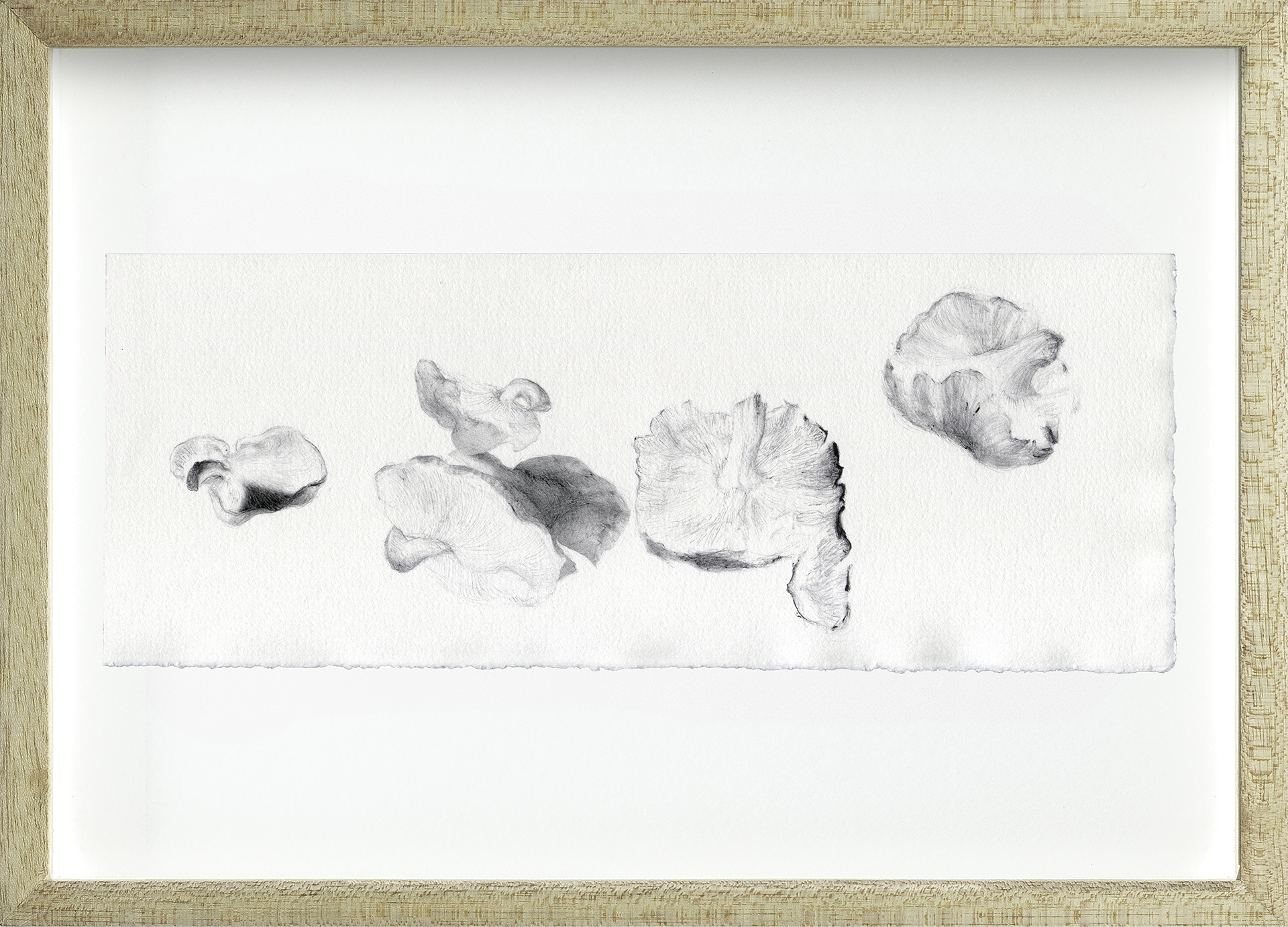

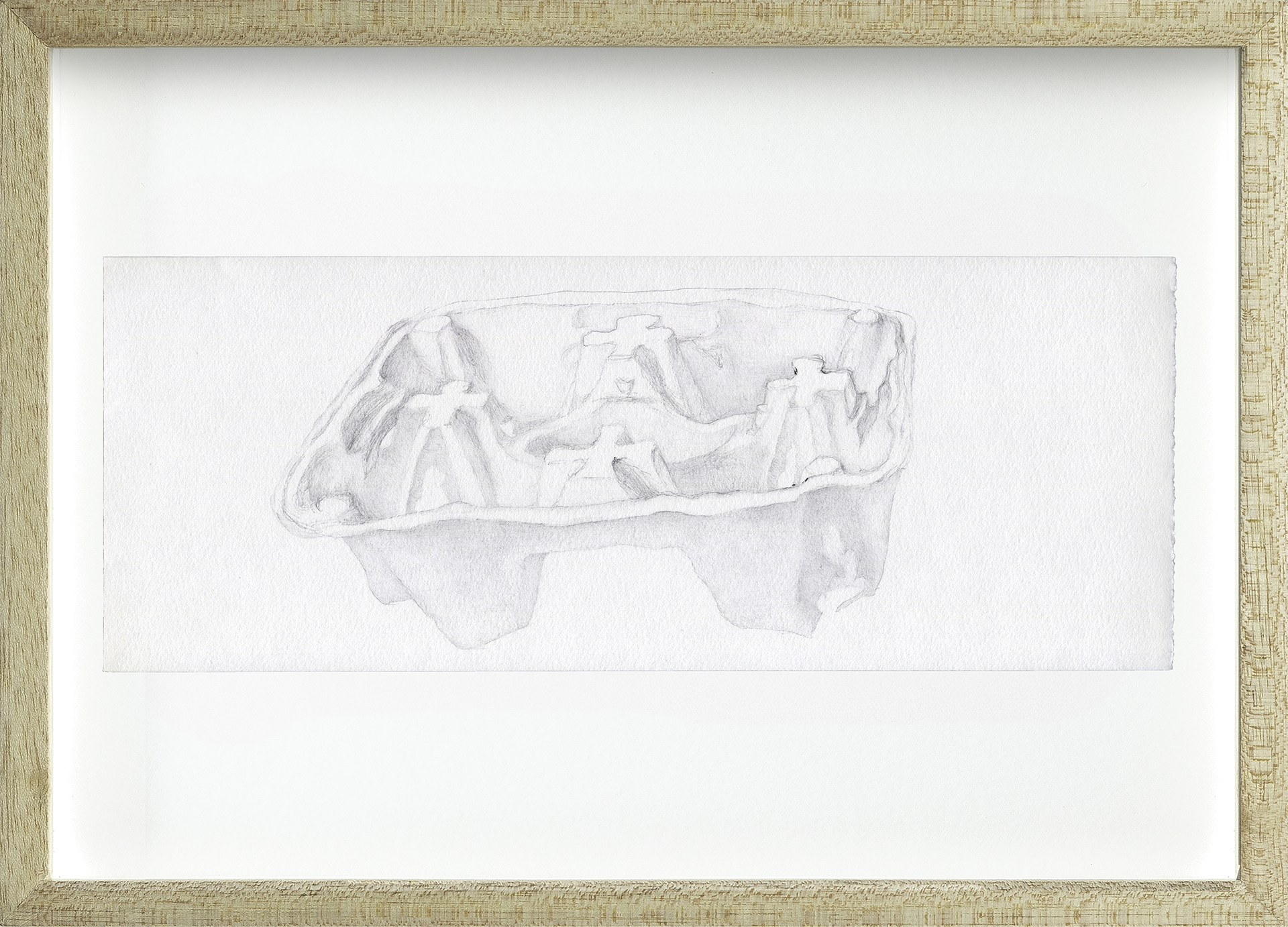

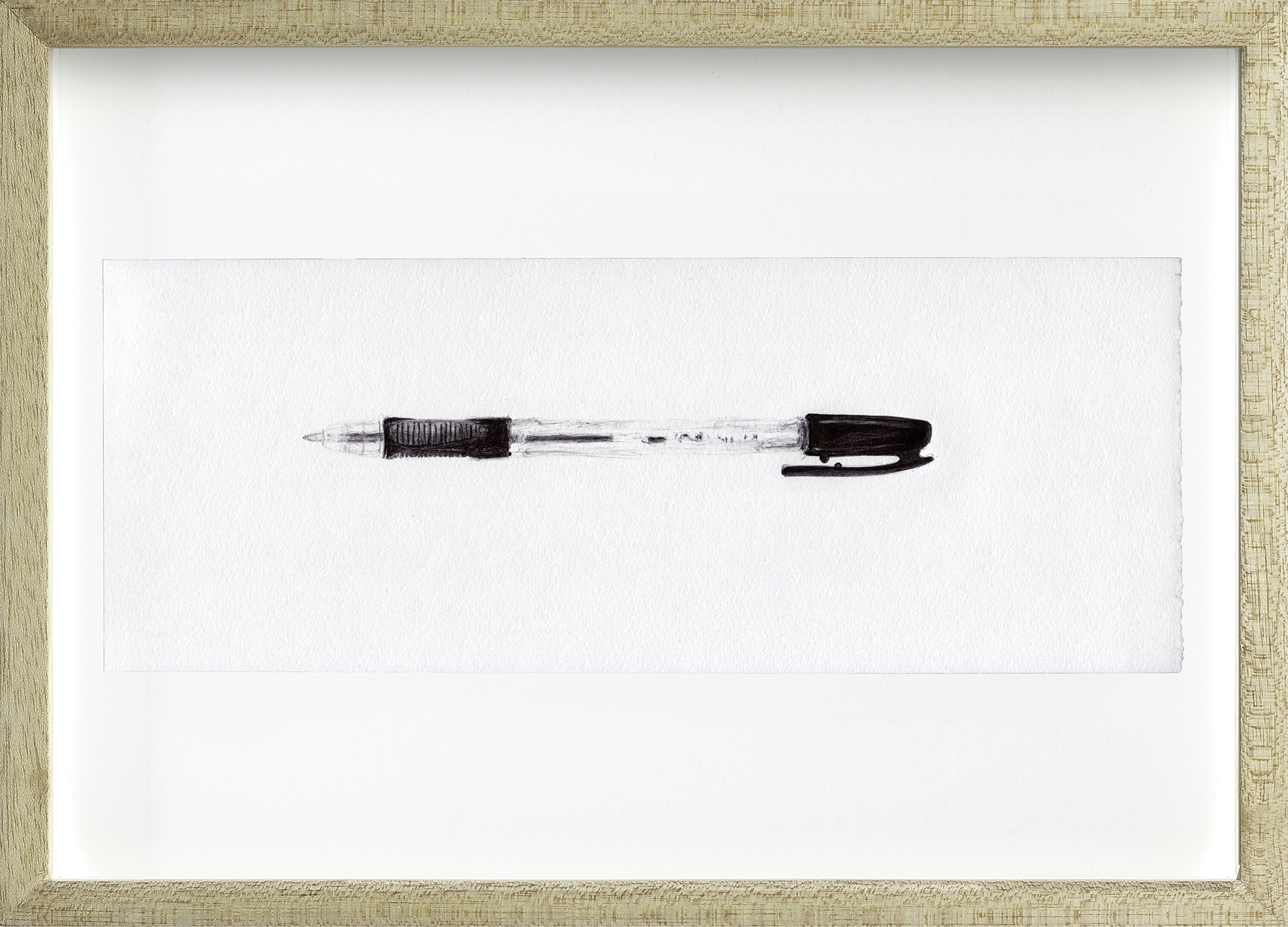

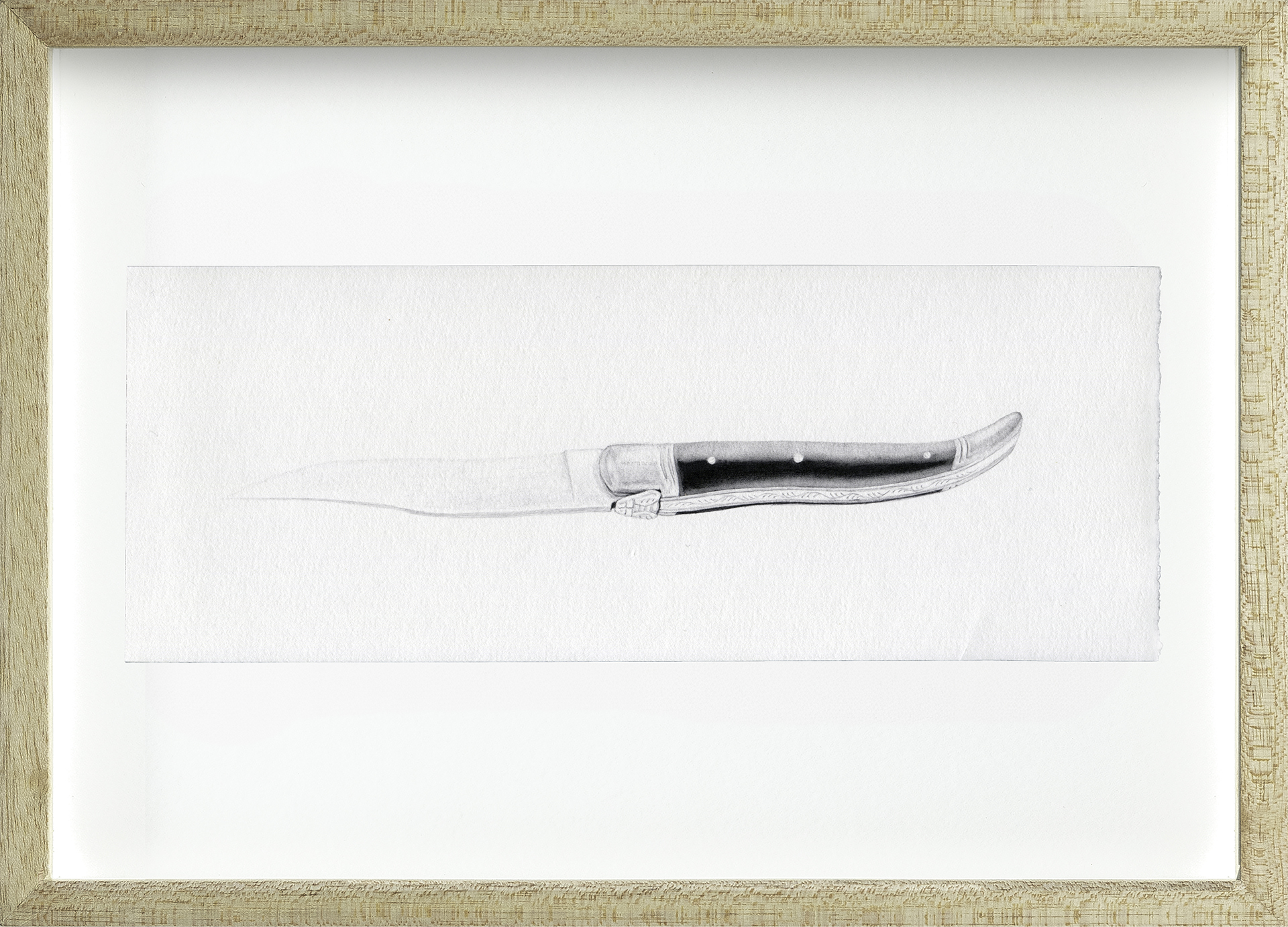

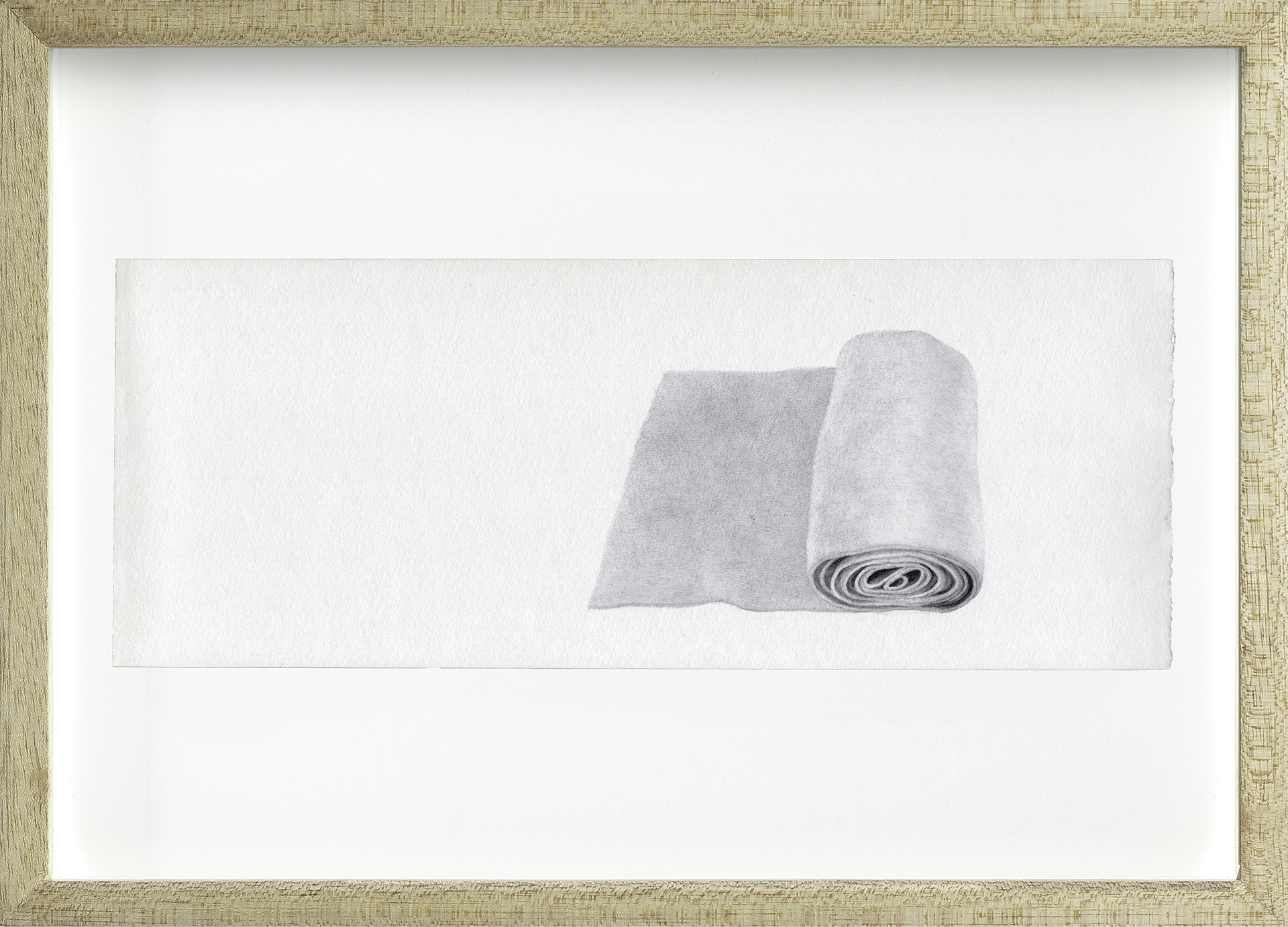

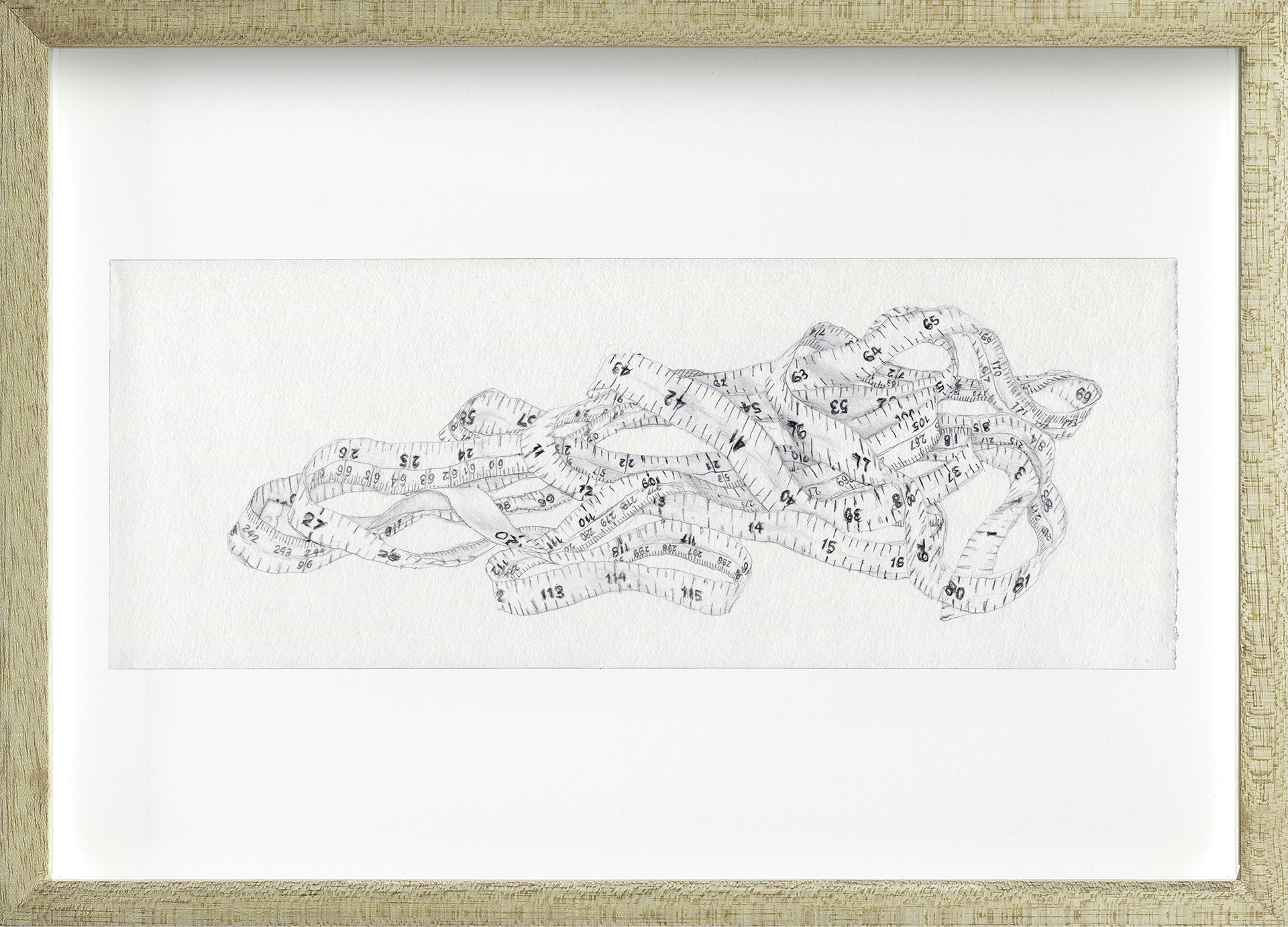

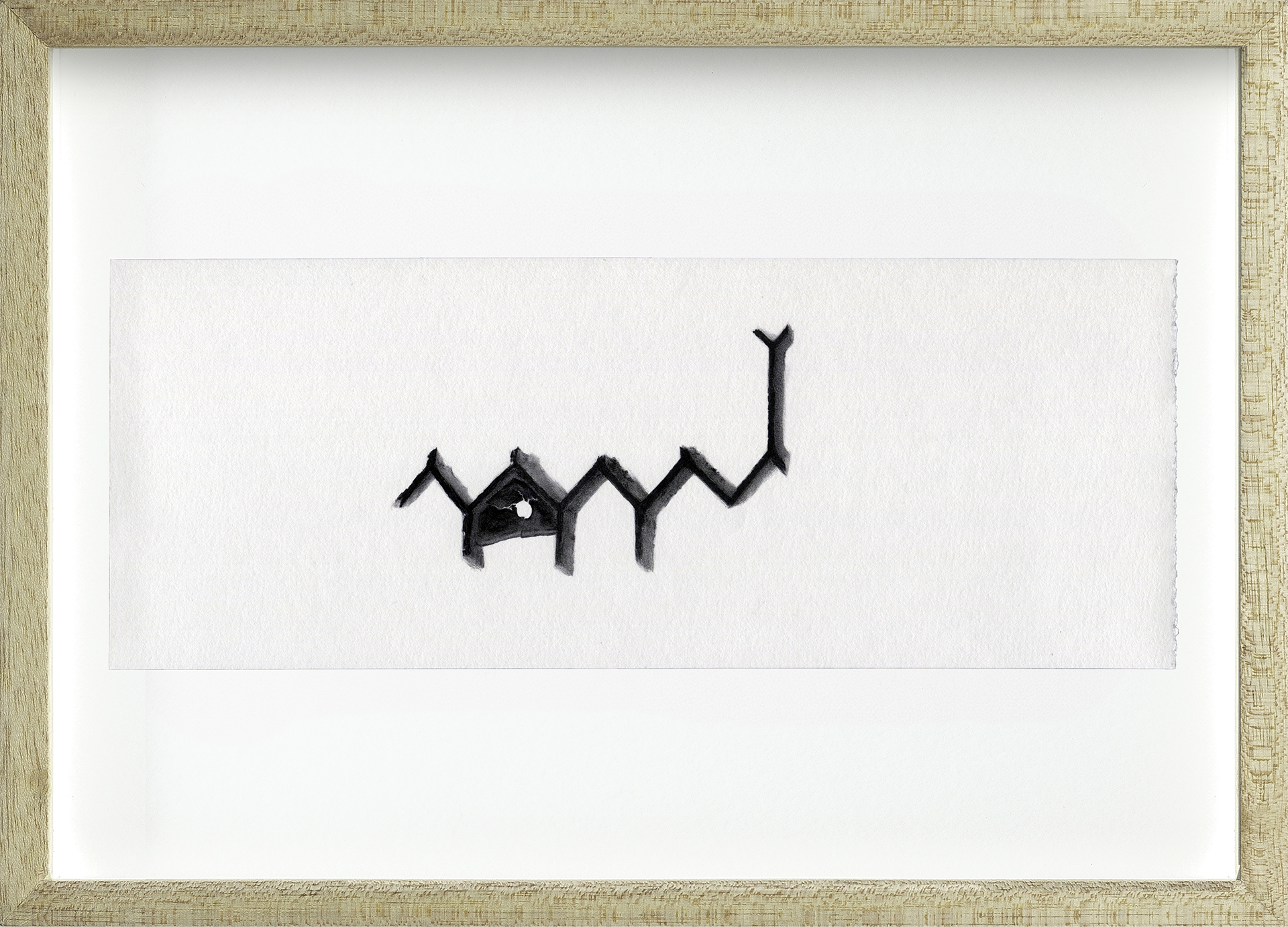

Entangled Pairs consists of 100 lifelike ballpoint pen drawings of everyday objects: a glove and a plastic water bottle; a teapot and a hammer; a tomato and a butternut squash. These consecutively-made renderings are paired and split from their counterparts across two continents. The exhibition format embodies the concept of quantum entanglement—the phenomenon in which energetically intertwined particles are inextricably linked regardless of spatial or temporal distance and "the closest thing to magic that can happen in physics".

Orara's drawings in this body of work only realize their full potential once exhibited across geographically separated spaces, here split thousand of miles apart across Silverlens' New York and Manila galleries. In splitting these pairs across continents, the galleries themselves become entangled and invite audiences to reflect on and reconcile the dualistic ways in which we see ourselves and our world. By using the parallel of quantum entanglement, Entangled Pairs tugs at the invisible threads that bind and loosen our notions of self, relationships, space, time, simultaneity, reality, while transporting us to that "space that we never visit".

THE MIRROR OF EVOCATIONS

by Luis Camnitzer

When I first met Renato in 2000, he showed me realistic ballpoint pen drawings, minutely detailed, which, on the basis of a superficial quick look, I started to challenge as examples of skillful rendering. Yes, they were exquisite, so much that I had to fight my pleasure. But what was the discourse? Was there a discourse? Did they address some hidden problem and possibly also solve it?

From his response, I learned there was indeed a discourse, a problem, and that he had solved it. Amazingly, they were not renderings. They showed the “rebirth” of the objects he picked. He started from scratch and only ended when he “fit” the image we knew of the object, but now enriched by the growing process. The drawings, therefore, had to be classed as a rendered version of something we would never be able to fully grasp. Only looking like known objects, they contained the intangibility the actual objects were lacking. Now they were complete and true.

The pieces were part of an endless series called of “Ten Thousand Things that Breathe,” a title and project that gave away that the objects he drew were not really fully known. It was this extra what he really was after. Far from any effort to anthropomorphize, the drawings were more a way of bowing towards the models and a show of respect. Renato described all this in very modest words (my description here is a pompous version). I wanted to be persuaded that he wasn’t just copying things, which would be a cop out.

We went over Borges’ fictions, Zen, religions, and whatever cosmologies came to my mind, but he had them all under control. I actually was very moved by the work, something I didn’t tell him. I also realized that his work was filling a gap that schematic views of art historians (and artists) had created to simplify their jobs. From a traditional figuration point of view, Renato’s work didn’t qualify for a membership in the realist ranks. He was actually a conceptual artist who only used figuration to make a point, or rather, to catch a point. He was not interested in making traces on paper that faithfully corresponded to the points that constructed what we see as reality. Instead, he was reaching out to things that belonged to other spheres of knowledge. But then, from a conceptual art point of view, he was another realist artist, and for conceptual artists he had to be looked at with suspicion. But, in fact, he was infiltrating academic art and bringing it into the field of pure thought. So, though actually filling a gap between two aesthetics, shunned by both sides because he couldn’t be labeled, he was let fall through a crack.

It’s now nearly a quarter of a century after we first met, and over three decades after he started his project, and his work continues to elude definitive placement. While the first pieces focused on themselves, on what life in its many interpretations might be when contained in the shell of what we see as objects, he now has a new series. This one is about entanglement and this takes his drawings a step further. Entanglement challenges our ideas about location and is the closest thing to magic that can happen in physics. In quantum theory, entanglement is the behavior of particles that both defy distance and our common sense. This, so much, that we’re relieved to confine its implications to the subatomic space where it can’t bother our sense of order.

It is fascinating, however, to think of the questions entanglement raises were it to work in our scale and in normal life. Am I smiling following the lip movements of someone thousands of miles away from me, across the ocean? Is my wrinkle also your wrinkle? And if that is the case, how can I prove it? If simultaneity exists, how can we perceive it? The image of any pairing, two smiles, two wrinkles, two individuals that lose their uniqueness, won’t work. I’m still whoever I am, and can’t be in both places at the same time to check these things out. Simultaneity is a nice concept, but it works better in description than in perception. To be seen it requires that two locations share the same location, that two moments are the same moment.

Renato dives into this conundrum with a powerful speculation about the meaning of entanglement. The relief of subatomic confinement is disturbed. Each of his pieces is like a mirror defying our learned idea of mirroring, in which we presume one meaning bears the truth and the other being is only a print of the truth. The secret in Renato’s entangled pairs is that neither image, separately, no matter how persuasive and satisfying as a drawing, is the original, and neither is the reflection. His entangled images don’t even look the same. Nevertheless, both sides perform as original and reflection, leaving the meaning of the piece to reside in the middle. It is in the in-between where their sameness and simultaneity is established. We end up in this in-between. We are guided to learn to look in a new way, to focus not on the separate drawings but on what lies in the space we never visit.

When preoccupied with how he draws, (is he only rendering?), one misses that the problem being addressed and solved is not in the drawings but emanates from them. Failing to understand this was the mistake I made when we first met, and now I keep looking at them again and again.

Renato Orara (b. 1961, Bicol, Philippines; lives and works in New York, USA) is an artist recognized for his creations using a ballpoint pen on paper. His drawings portray objects devoid of their context, meaning, and narrative, surpassing the limits imposed by language and material constraints. With a conceptual foundation rooted in interventions and public performance arts in Manila in the 70s, Orara resurfaced from an eight-year Zen meditation hiatus to embark on a renewed career with the use of ballpoint ink. Over time he reintroduced concepts into his art, branching out into series of works such as Drawer Drawings, Iraq Memorial, Bookworks, Bloodworks, and Entangled Pairs.

His works are in numerous private and public collections including the Museum of Modern Art, NY, the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, TX, and the Singapore Art Museum. Exhibitions include the US Palo Alto Cultural Center, Hosfelt Gallery, Andrea Rosen Gallery, Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery, Gallery Joe, OSP Gallery, Joseé Bienvenu Gallery, Leo Fortuna Gallery, the Travelling Gallery, Dominique Fiat Gallery, Alon Segev Gallery, and Silverlens Gallery.

Installation Views

Works