re_mediations

Gary-Ross Pastrana

Silverlens, New York

About

Remediative Form

by Carlos Quijon, Jr.

A keen attentiveness to material qualities motivates the transformations that play out in Pastrana’s artmaking. The metamorphoses are far from mechanical: two rings into sword, skin into flower, car parts to a branch of a tree, book pages into leaves, half of a ladder into a charred bird, perhaps a crow. Analogous affinities signal each change, and it is the artist that traffics these transformations.

In Two Rings (2008), Gary-Ross Pastrana borrowed two gold rings from his mother, melted them and created a small sword, wounded himself with it and by the end of the process remade them into their original form—two gold rings. Flanked by two photographic prints of the titular two rings is another photograph: the artist’s arm, a bright streak of blood as a flimsy metal stick presses firmly against skin, the artist’s own hand holding what proves to be a sharp object. The sharp stick is a miniature sword, complete with a miniature cross-guard and a miniature hilt held between the artist’s index finger and thumb. While the two prints are mirror images, the photograph of the artist’s wounded arm breaks this juxtaposition, foils the mirroring. The foiling discerns a particular tendency in Pastrana’s practice that is the premise of the essay: the artist wounding himself, the presence of the artist in this composition, stages a remediative activity, a relay of mediations that facilitates and annotates transformation.

Pastrana is the intermediary between form to form, found object to raw material. This intermediation is an aesthetic agency that is further fleshed out in the artist’s practice. In these transformations, Pastrana enlists the help of other artisans: a goldsmith, a metal worker, a make-up artist, an auto mechanic. This is a relay of mediations, interventions into the life of things. Pastrana takes the rings from his mother, asks a goldsmith to melt the metal for him and asks him to create a sword, conserving as much of the material’s weight as possible so that he can change the sword back to its original form after. This materialist choreography—decomposing found object into raw material, assuming another form, and then decomposing this new form back to raw material and then back to its initial state—insists on an annotation of forms and the processes that allow this choreography. In particular, it is interesting to see how this transmutation releases the work or the work’s found quality—how it pre-exists artistic activity and prefigures the creative labor of the artist—and remediates it, yoking it back to a process of making—displacing artistic originality with a poetics of transitional unoriginality.

I am interested in how Pastrana’s mediations constitute a particular artistic strategy. This aspect of Pastrana’s practice has been described as an aesthetic tendency of “metabolic, self-renewing form.” While this is an apt description for the most part, the object and the motivations of such a metabolism or self-renewal are usually left out. Pastrana’s works gesture toward a practice built on “remediative form.” On the one hand, pertinent in Pastrana’s procedure is his use of found objects as raw materials—not in the sense of existing materials becoming part of a new assemblage but in the sense of how each finished and made thing is broken down to constituent materials, which in turn communicate qualities at the core of each object, from which particular transformations are intuited.

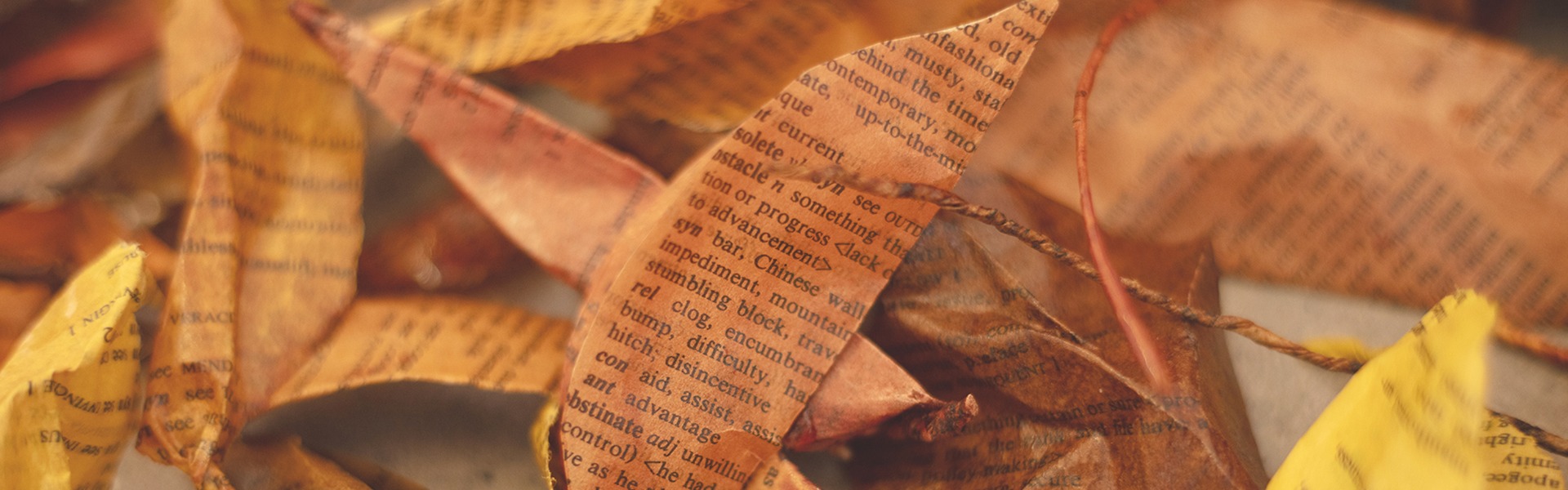

We see this method at work in Like a Clock From Which Time Detached and Fell (2024), where using the thesaurus he had owned and used during his undergraduate years Pastrana created loose leaves varnished to look like they had fallen from a tropical fruit tree and gathered into a clump to look like they just have been swept and put aside together. Like a Clock From Which Time Detached and Fell takes after an earlier work titled The Fall of Meaning (2000), where he produced the same leaf-like objects and installation this time using the dictionary that he owned during his younger years. The work riffs on the nominal similarities between leaves (plant) and leaves (pages). It also conceptually plays out ideas around the synonym in how Like a Clock From Which Time Detached and Fell was created in “the likeness of the old work, not entirely an exact copy or edition.”

This procedure consists of recurring and recursive mediations, not just of the object itself but also the mediation of Pastrana’s own practice and labor by way of collaborative ways of working. Collaboration becomes a way to interrogate artistic expertise or mastery as it also becomes a process that displaces the exceptionality or singularity of the artistic vision through the inclusion of other agencies and masteries. In 99% (2014), for example, Pastrana creates a sculptural object from the parts of a broken-down car that he failed to sell. From the vehicular bits and bobs, he worked with an auto mechanic and then a metalsmith to create a steel stem gracefully growing out of a part of the car’s steering column, bearing in one of its smaller branches a golden bell that looks like a berry. In Fellen (2017), Pastrana created a wilting flower using human skin, from the petal to the twig to the leaves. The artist collected skin from a friend who has a condition that makes them produce excess. To complete the work, Pastrana asked a professional make-up artist to render the flower more beautiful using whichever color story was on trend in makeup during this time. The resulting object is a delicate, colorful flower made of human skin.

On the other hand, the aspect of remediation alluded to in the theorization of “remediative form” might also refer to the myriad ways in which the artmaking becomes a way of remedying or remediality: unmooring things not only from fetishistic relations but also from overdetermined relations of use, ownership, familiarity or intimacy, and even literalness. In this context, remedy or remediality is also a method of replenishment: Pastrana’s metamorphic practice plays with the potential of materiality to imbue with or derive from found materials poetic and productive potency through analogy or unusual juxtaposition or through the embedding of the found materials into other networks of dissemination or dispersal.

In Two Rings, for instance, the wounded arm recalls a blood pact, alludes to a contractual engagement that the two rings might also call to mind. It can also be read as a form of renewal of the artist’s interest or even investment in these objects that his mother treasures and for a time has been part of their mother-son ritual of letting him wear jewelry that she owns. A comparable case can be made for the work 99%, where faced with questions of ownership triggered by the flagging of the artist’s car as a possibly stolen vehicle, the artist reconfigures the entire object into an assemblage of parts which he then refunctions and reframes as material for other objects. Both works also function as a remedial process for the invisible and alienated labor of the goldsmith, the metal worker, the auto mechanic, whose labors are essential in the process of creating Pastrana’s works.

The remediative form offers a slippage from ideas of self-renewal or metabolism or even alchemical transfiguration or reconstitution. The found material is not necessarily strictly found and the new form is not exactly new. In the process of remediation, the artist leans into any object’s physical properties or material qualities and lets these constitute the object’s metamorphic matrix. It is not renewal or absorption or creation that structures the trajectory of the transformation but a more enduring intentionality toward the social life of things. It is in this way that Pastrana’s mediations become remediative: each found thing is an invitation to imagine otherwise, each object-form its own rudimentary, each quality an affordance that intuits replenishing, metamorphic potential.

Gary-Ross Pastrana (b. 1977, Manila, Philippines; lives and works in Manila) is an artist deeply immersed in the philosophies surrounding concepts, objects, and art. His highly conceptual pieces, rich with poetic intensity, maintain an unobtrusive subtlety. Incorporating dynamic and nonsequential images along with other modes of study such as music and science, his creations form a new textual narrative.

In 2006, Pastrana received the Cultural Center of the Philippines’ Thirteen Artists Award. Since then, he has shown at the Singapore Art Museum, Metropolitan Museum of the Philippines, the Jorge B. Vargas Museum, and was part of the 2019 The Art Encounters Biennial in Romania, 2019 Singapore Biennale, 2012 New Museum Triennial in New York, 2010 Aichi Triennale, and 2008 Busan Biennale. In 2004, he co-founded Future Prospects art space. In addition to his artistic career, Pastrana curates and organizes exhibitions in Manila and abroad. Exhibitions include Erstwhile Maps, CASE Space Revolution, Bangkok, Thailand (2020); Every Step in the Right Direction, Singapore Biennale, Singapore (2019); The Art Encounters Biennial, Romania (2019); An Opera for Animals, Para Site, Hong Kong (2019), Rockbund Art Museum, Shanghai (2019); Utopia Hasn’t Failed Me Yet, Silverlens, Manila (2018, solo); The Extra, Extra Ordinary, Museum of Contemporary Art and Design, Manila (2018); The Other Face of the Moon, Asia Culture Center, Gwangju (2017); Clock, Map, Knife, Mirror, ROH Projects, Jakarta, (2016, solo); Summa, Vargas Museum, Manila (2014, solo). Pastrana received his Bachelor’s degree in Painting from the University of the Philippines, where he was awarded the Dominador Castañeda Award for Best Thesis. He has gained considerable experience and exposure within the region, with residencies in Bandung, Kyoto, Bangkok, and Singapore.

Installation Views

Works

In Two Rings (2008), Gary-Ross Pastrana borrowed two gold rings from his mother, melted them and created a small sword, wounded himself with it and by the end of the process remade them into their original form—two gold rings. Flanked by two photographic prints of the titular two rings is another photograph: the artist’s arm, a bright streak of blood as a flimsy metal stick presses firmly against skin, the artist’s own hand holding what proves to be a sharp object.

While the two prints are mirror images, the photograph of the artist’s wounded arm breaks this juxtaposition and foils the mirroring. The foiling discerns a particular tendency in Pastrana’s practice: the artist wounding himself, the presence of the artist in this composition, stages a remediative activity, a relay of mediations that facilitates and annotates transformation.

In Like a clock from which time detached and fell (2024), using the pages of the thesaurus he owned and used during his undergraduate years, Pastrana creates loose leaves varnished to look like they had fallen from a tropical fruit tree and gathered into a clump and swept aside together. This work takes after an earlier work titled The Fall of Meaning (2000), where he produced the same leaf-like objects and installation, this time using the dictionary that he owned during his younger years. The work riffs on the nominal similarities between leaves (plant) and leaves (pages).

The aspect of remediation found here refers to the myriad ways in which the artmaking becomes a way of remedying or remediality: unmooring things not only from fetishistic relations but also from overdetermined relations of use, ownership, familiarity or intimacy, and even literalness. In this context, remedy or remediality is also a method of replenishment: Pastrana’s metamorphic practice plays with the potential of materiality to imbue or derive found materials with poetic and productive potency through analogy or unusual juxtaposition, or through the embedding of the found materials into other networks of dissemination.

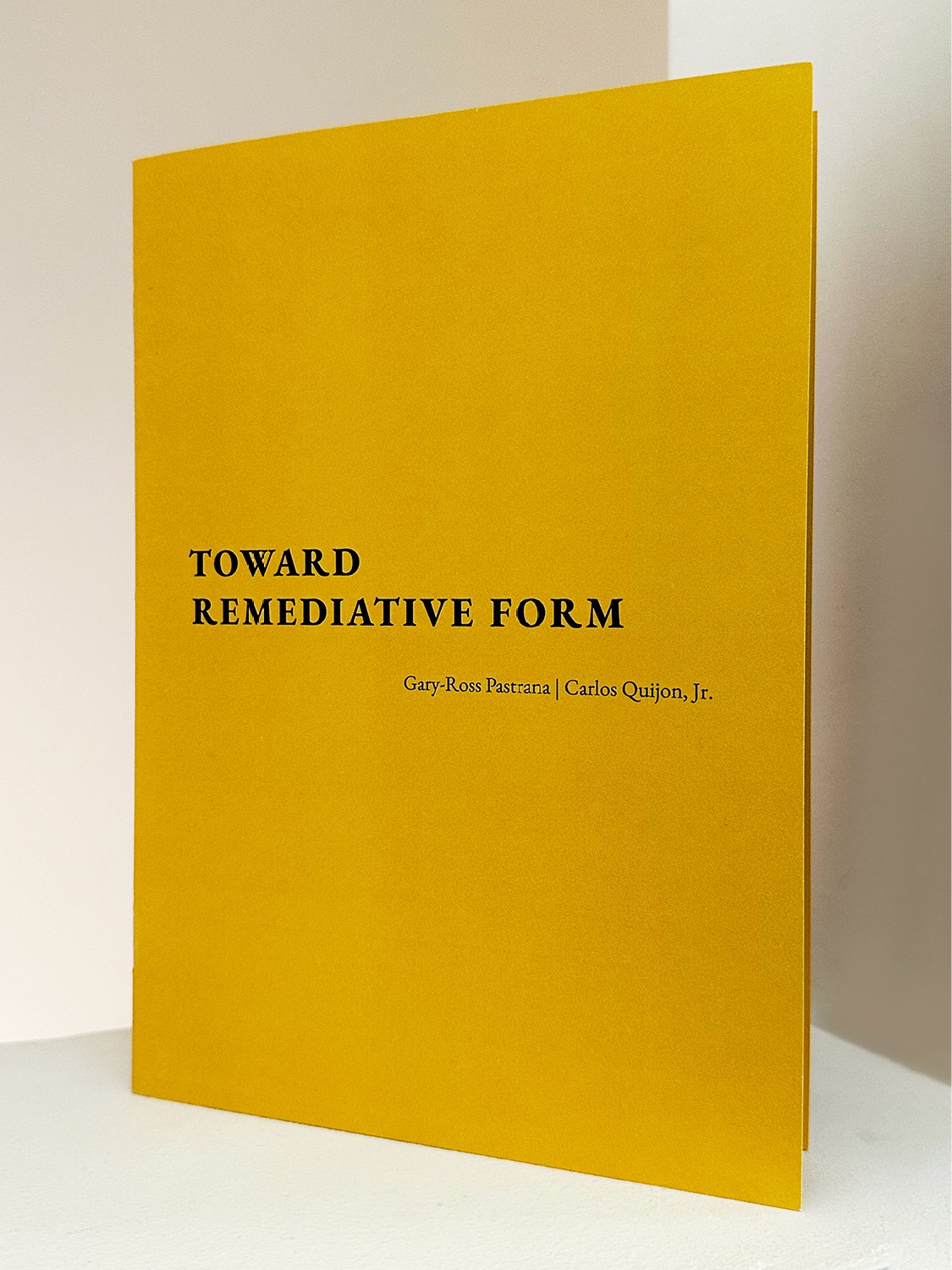

Working together, Gary-Ross Pastrana and Carlos Quijon, Jr. composed their first zine for re_mediations. Their collaboration echoes the artist’s method, not just of the objects themselves but also as a mediation of Pastrana’s own practice and labor, by way of collaborative ways of working. Collaboration becomes a way to interrogate artistic expertise or mastery as it also becomes a process that displaces the exceptionality or singularity of the artistic vision through the inclusion of other agencies and masteries. In his material transformations, Pastrana enlists the help of other artisans: goldsmiths, metal workers, auto mechanics, makeup artists. This is a relay of mediations, interventions into the life of things.