About

Soil’s Science Fictions

By Simon Wu

In April 1981, on the island of Mindanao in the Philippines, shortly after a spring rain dispelled a torrid humidity, construction worker Edilberto Morales sensed that his plough had come into contact with something non vegetal. Most days, he felt the earth give way without friction, only the torn veins of roots and leaves a sign of the actual carnage. White noise often filled his mind as he moved earth from one place to another, and from the cockpit of his tractor, he imagined he looked out from a spaceship, wandering the cosmic expanse of the dark earth underneath him.

Perhaps today he had collided with an asteroid. Morales was one of many heavy machinery operators tasked with quarrying the soil from a nearby mountain top into a landfill for an irrigation project in the province of Surigao del Sur. He stood above a 100 meter wound in the earth as dark as the shores of the water nearby was lapis. In precolonial times, the soil had been inhabited by Visayan Surigaonon people in the coastal areas, as well as Lumad groups in the interiors. In eastern Mindanao, as well as in a belt running from the Bicol region of southeastern Luzon to the Gulf of Davao, abacá trees––a strand of banana famous for their threads which can be woven into rope, paper, and textiles––depend on this soil for their tall leafy stems.

Morales peered into the soil. He crouched down, balancing on his back foot. Prying apart the darkness with his hands he saw a soft yellow glimmer: a small metal bowl, partly dented. Morales’ asteroid, he would come to learn, was the site of 22 pounds of precious gold artworks––bowls, necklaces, sculptures, and other fine crafts–-dating to the precolonial Philippines, from a time more than 500 years before Ferdinand Magellan would reach the archipelago in 1521.

Squinting into the dark, Morales thought he saw a glint of light and startled, worried it was a snake. He looked again. He saw the snake was actually a gold sash, fine gold somehow woven to resemble rope. He pulled it from the soil. Later, the sash would come to be known as a fine example of a Hindu upavita, or sacred thread, possibly belonging to an ancient polity of Butuan in northeastern Mindanao, where the elite could afford stunning accessories of gold. But for now, he let it sit.

In an eerie mirror of Magellan’s thieves in the 16th century, looters descended on Morales’ discovery, dissecting an archeological site into a quick buck. Over 1,000 pieces of gold–– now known as the Surigao Treasure–– would be dispersed amongst grave diggers, farmers, and fishermen. Morales and his family went into hiding, and at one point his family was even kidnapped and sold back to him for ransom. He fled the island and changed his name.

But Morales’ snake did escape the soil. It grew one thousand times in size, and in the process shed its gold skin to reveal an abacá core. It became the artist Patricia Eustaquio’s sculpture, Fountain 001. In the gallery, Morales’ snake multiplied. They became large, inert serpents, ready to guide us equally into the past as into the future. Abacá, also known as “Manila Hemp” (the namesake for the Manila envelope) is a heavy and stiff fiber, but its pliancy can be hard-earned from many hours of weaving. Abacá was and continues to be a major export of the region since Spanish colonial reign, useful in ships, papers, and textiles. In Eustaquio’s imagination, however, the material is reborn through the vernacular craft of precolonial Philippine jewelry. Through Morales’ discovery and Eustaquio’s reinvention, it becomes a material science fiction of Filipino creativity outside of colonial interference.

Eustaquio enacts a similar “material science fiction” in her digitally woven tapestries, where she edits paintings by grand Philippine “masters” like Fernando Amorsolo into impressionistic reimaginings. Yet a work like An Unraveling (Conversation Among Ruins, After Amorsolo), created in collaboration with a team of artisans, reconsiders Amorsolo’s complex legacy. Is the veneration of Amorsolo as a Spanish-educated Filipino “native” the fetishization of colonial artistic metrics over existing precolonial craft? In another work, White Lies (Balanced On A Ball), 2023, more materials, other than abacá, begin to be woven into this revision of history: Inabel, a kind of cotton local to the Ilocos region of the Philippines, dried grass, canvas and other upcycled fabrics from discarded clothing. Eustaquio poses her questions thread by thread, through the fruits of the islands’ soil, as if by resynthesizing the image she might find the answers.

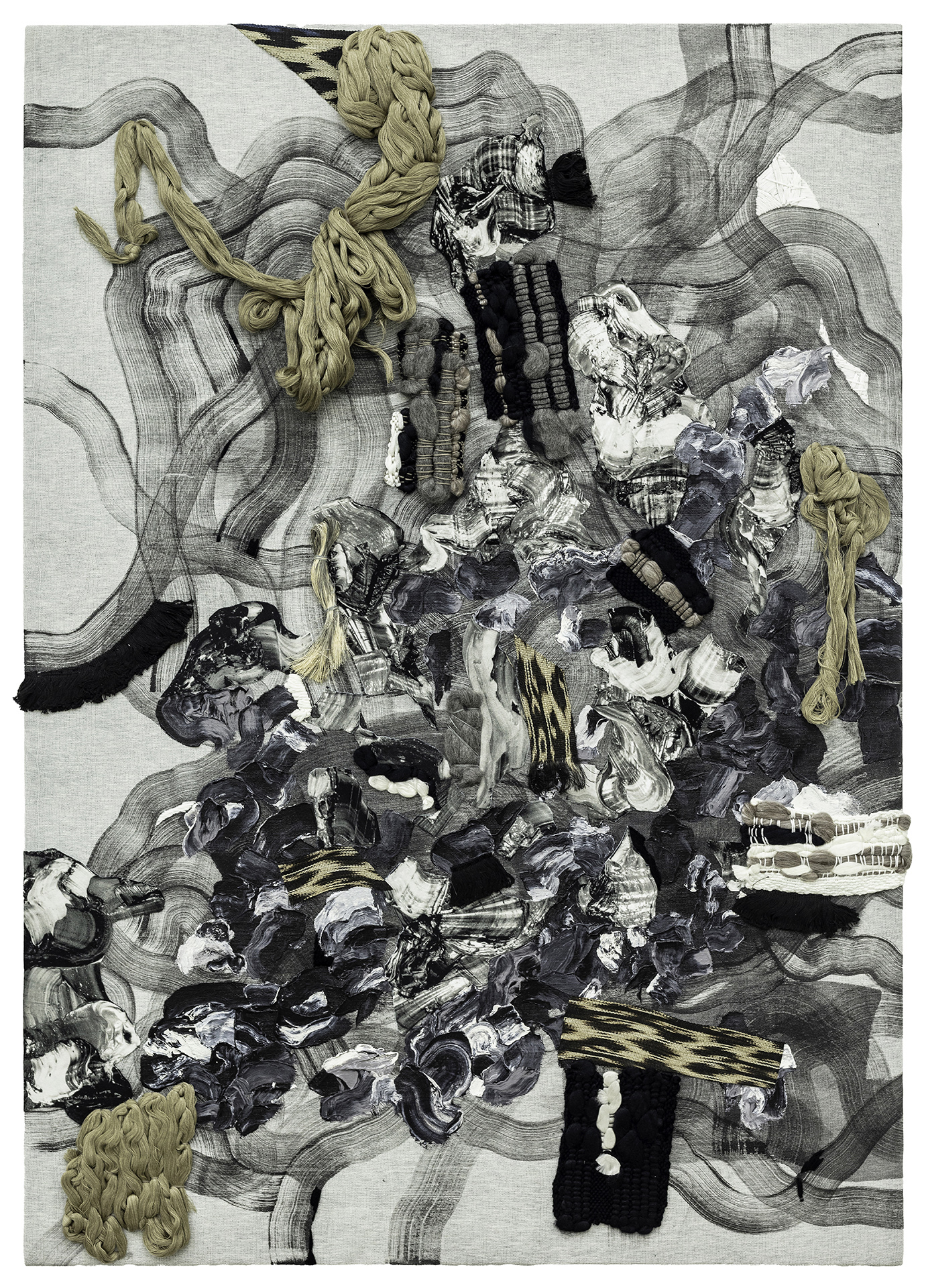

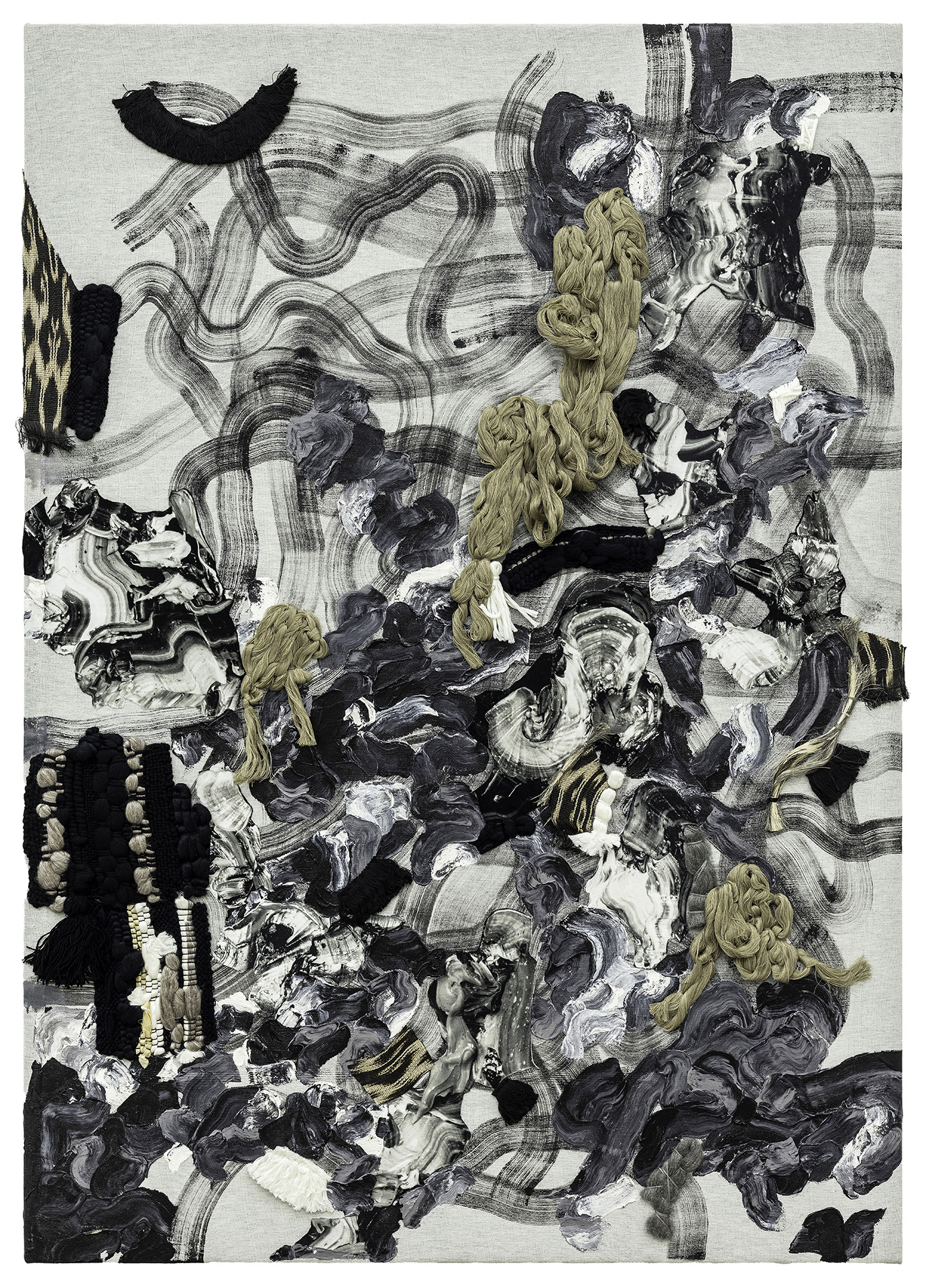

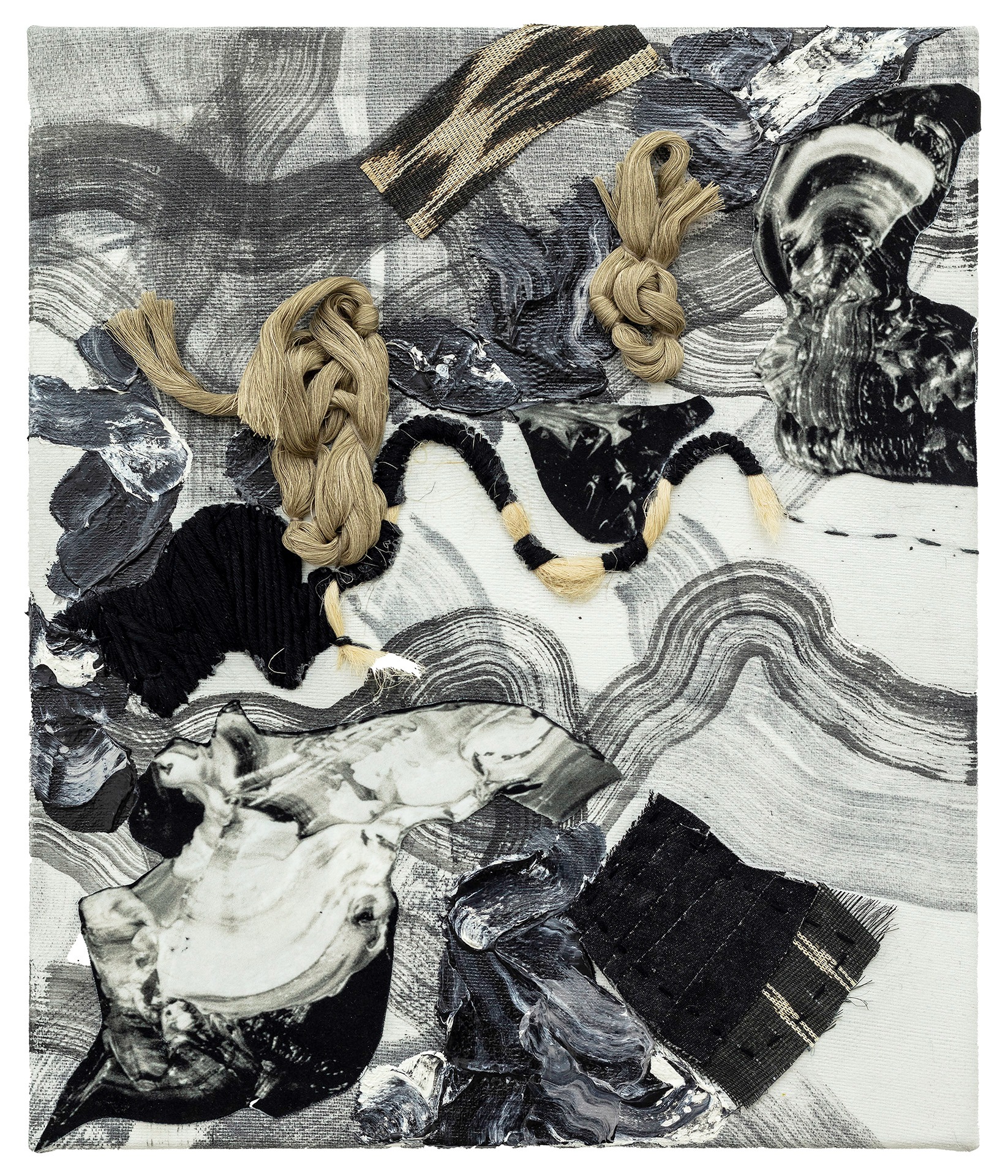

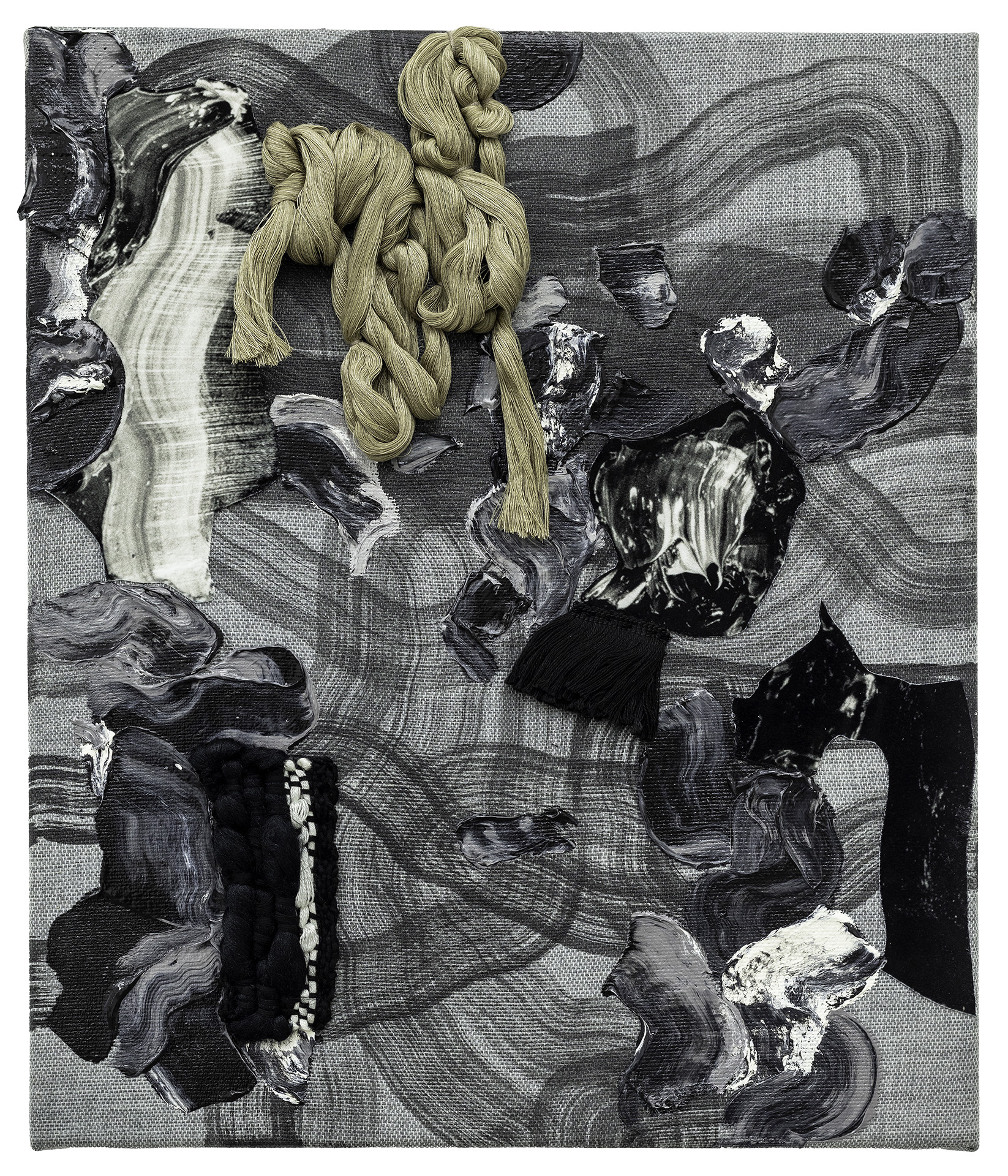

And if Morales’ snake escaped, transforming into another form in the gallery, perhaps his asteroid––that unidentified mass of gold hiding in the soil––also escaped. Eustaquio’s paintings of material science fiction denature even further in her Frayed Garden (2024) series, where swirls of abacá, velvet, and cotton, become brushes of paint. Like her Fountain snakes, these paintings play with scale: perhaps we are looking at a magnified version of the threads of the painting in White Lies or An Unraveling, or immaterial fabric for a mythic deity. Eustaquio’s work is a form of “mining”; from her own cockpit, she wanders the cosmic expanse of the dark earth underneath her.

When Edilberto Morales first encountered the Surigao treasures, he took whatever he could carry in a rice sack and brought them back to his home. After standing for a few minutes, he covered them with bananas. A laborer with limited formal education, he was unsure of how to monetize his find. He decided to bring it to the Parish Priest, who would ultimately betray him, spreading word to looters and selling off Morales’ portion himself. But let’s linger, for a moment longer, however, on the image of Morales’ asteroid, covered in gold snakes. The clink of a metal plough finding metal. A rice sack holding a precolonial past, adorned with an armor of bananas, pretending to be nothing more than what the soil gave it.

Patricia Perez Eustaquio (b. 1977, Cebu, Philippines; lives and works in Benguet Province, Philippines) is known for works that span different mediums and disciplines—from paintings, drawings, and sculptures, to the fields of fashion, décor, and craft. She reconciles these intermediary forms through her constant exploration of notions that surround the integrity of appearances and the vanity of objects. Images of detritus, carcasses, and decay are embedded into the handiwork of design, craft, and fashion while merging the disparate qualities of the maligned and marginalized with the celebrated and desired. From her ornately shaped canvases to sculptures shrouded by fabric, their arrival as fragments, shadows, or memories, according to Eustaquio, underline their aspirations, their vanity, this ‘desire to be desired.’ Her wrought objects—ranging from furniture, textile, brass, and glasswork in manufactured environments— likewise demonstrate these contrasting sensibilities and provide commentary on the mutability of perception, as well as on the constructs of desirability and how it influences life and culture.

A recipient of The Cultural Center of the Philippines’ Thirteen Artists Awards, Patricia Perez Eustaquio has also gained recognition through several residencies abroad, including Art Omi in New York and Stichting Id11 of the Netherlands. She has also been part of several notable exhibitions, such as The Vexed Contemporary in the Museum of Contemporary Art and Design, Manila; That Mountain is Coming at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, France; and An Atlas of Mirrors in the 2016 Singapore Biennale.

Installation Views

Works

In this entirely new body of work, Eustaquio’s materially driven process turns to handweaving massive sculptures of abacá. Also known as “Manila hemp”, the abacá fiber derives from a plant native to the Philippines and was a major trade commodity in the colonial era. It is both fine enough to be woven into fabric for clothing and tapestry and strong enough to be used for shipping cordage, as it has been for centuries—shipping ropes from Manila hemp were not only featured in the almost two hundred galleons built in various Philippine shipping yards and plied the Manila-Acapulco trade route, but also in the thousands of paraws, balangays, and other boats that generations of Filipinos used for trade and travel around the Asian seas. Eustaquio, however, knits the abacá into the structure of a precolonial, gold Philippine jewelry (c. 1000 CE), scaling her works to over one thousand times the size of the original forms.

In this entirely new body of work, Eustaquio’s materially driven process turns to handweaving massive sculptures of abacá. Also known as “Manila hemp”, the abacá fiber derives from a plant native to the Philippines and was a major trade commodity in the colonial era. It is both fine enough to be woven into fabric for clothing and tapestry and strong enough to be used for shipping cordage, as it has been for centuries—shipping ropes from Manila hemp were not only featured in the almost two hundred galleons built in various Philippine shipping yards and plied the Manila-Acapulco trade route, but also in the thousands of paraws, balangays, and other boats that generations of Filipinos used for trade and travel around the Asian seas. Eustaquio, however, knits the abacá into the structure of a precolonial, gold Philippine jewelry (c. 1000 CE), scaling her works to over one thousand times the size of the original forms.

In this entirely new body of work, Eustaquio’s materially driven process turns to handweaving massive sculptures of abacá. Also known as “Manila hemp”, the abacá fiber derives from a plant native to the Philippines and was a major trade commodity in the colonial era. It is both fine enough to be woven into fabric for clothing and tapestry and strong enough to be used for shipping cordage, as it has been for centuries—shipping ropes from Manila hemp were not only featured in the almost two hundred galleons built in various Philippine shipping yards and plied the Manila-Acapulco trade route, but also in the thousands of paraws, balangays, and other boats that generations of Filipinos used for trade and travel around the Asian seas. Eustaquio, however, knits the abacá into the structure of a precolonial, gold Philippine jewelry (c. 1000 CE), scaling her works to over one thousand times the size of the original forms.

In this entirely new body of work, Eustaquio’s materially driven process turns to handweaving massive sculptures of abacá. Also known as “Manila hemp”, the abacá fiber derives from a plant native to the Philippines and was a major trade commodity in the colonial era. It is both fine enough to be woven into fabric for clothing and tapestry and strong enough to be used for shipping cordage, as it has been for centuries—shipping ropes from Manila hemp were not only featured in the almost two hundred galleons built in various Philippine shipping yards and plied the Manila-Acapulco trade route, but also in the thousands of paraws, balangays, and other boats that generations of Filipinos used for trade and travel around the Asian seas. Eustaquio, however, knits the abacá into the structure of a precolonial, gold Philippine jewelry (c. 1000 CE), scaling her works to over one thousand times the size of the original forms.

In this entirely new body of work, Eustaquio’s materially driven process turns to handweaving massive sculptures of abacá. Also known as “Manila hemp”, the abacá fiber derives from a plant native to the Philippines and was a major trade commodity in the colonial era. It is both fine enough to be woven into fabric for clothing and tapestry and strong enough to be used for shipping cordage, as it has been for centuries—shipping ropes from Manila hemp were not only featured in the almost two hundred galleons built in various Philippine shipping yards and plied the Manila-Acapulco trade route, but also in the thousands of paraws, balangays, and other boats that generations of Filipinos used for trade and travel around the Asian seas. Eustaquio, however, knits the abacá into the structure of a precolonial, gold Philippine jewelry (c. 1000 CE), scaling her works to over one thousand times the size of the original forms.

In this entirely new body of work, Eustaquio’s materially driven process turns to handweaving massive sculptures of abacá. Also known as “Manila hemp”, the abacá fiber derives from a plant native to the Philippines and was a major trade commodity in the colonial era. It is both fine enough to be woven into fabric for clothing and tapestry and strong enough to be used for shipping cordage, as it has been for centuries—shipping ropes from Manila hemp were not only featured in the almost two hundred galleons built in various Philippine shipping yards and plied the Manila-Acapulco trade route, but also in the thousands of paraws, balangays, and other boats that generations of Filipinos used for trade and travel around the Asian seas. Eustaquio, however, knits the abacá into the structure of a precolonial, gold Philippine jewelry (c. 1000 CE), scaling her works to over one thousand times the size of the original forms.

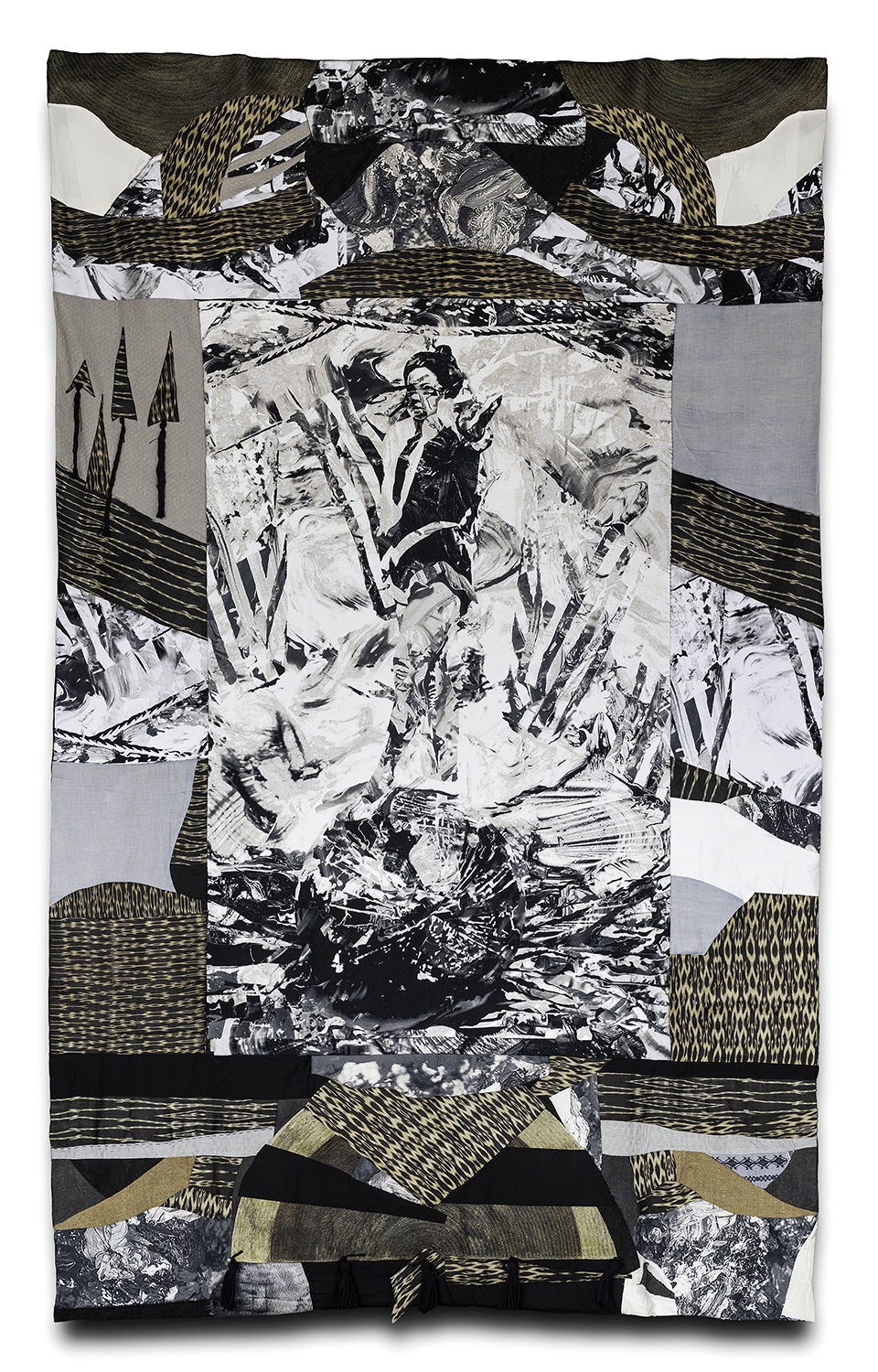

Eustaquio’s large-scale tapestries take historical paintings and imagery and digitally translate these into a black-and-white woven image. Looming nearly seventeen feet tall, White Lies (Balanced on A Ball) is based on 20th century photographs taken by Americans when the Philippines was a US territory (1898 – 1946). The suspended tapestry shows an acrobat from the Philippine circus balancing atop a ball, while festooned in Western clothing and American flags. The incongruity of the subject’s posture and dress as they are cast into character by the colonial gaze is striking, as if the disguise allows the subject to be finally seen. Rendered in fabric, the images are recast and woven into the language of costume and dress and urges the viewer to further examine the implications of what were once thought to be benign, superficial interventions. Eustaquio then extended the borders of the image with a native Philippine woven quilt, the materials of which possess a rich history long before the Philippines was colonized by either the United States or Spain.

In this entirely new body of work, Eustaquio’s materially driven process turns to handweaving massive sculptures of abacá. Also known as “Manila hemp”, the abacá fiber derives from a plant native to the Philippines and was a major trade commodity in the colonial era. It is both fine enough to be woven into fabric for clothing and tapestry and strong enough to be used for shipping cordage, as it has been for centuries—shipping ropes from Manila hemp were not only featured in the almost two hundred galleons built in various Philippine shipping yards and plied the Manila-Acapulco trade route, but also in the thousands of paraws, balangays, and other boats that generations of Filipinos used for trade and travel around the Asian seas. Eustaquio, however, knits the abacá into the structure of a precolonial, gold Philippine jewelry (c. 1000 CE), scaling her works to over one thousand times the size of the original forms.

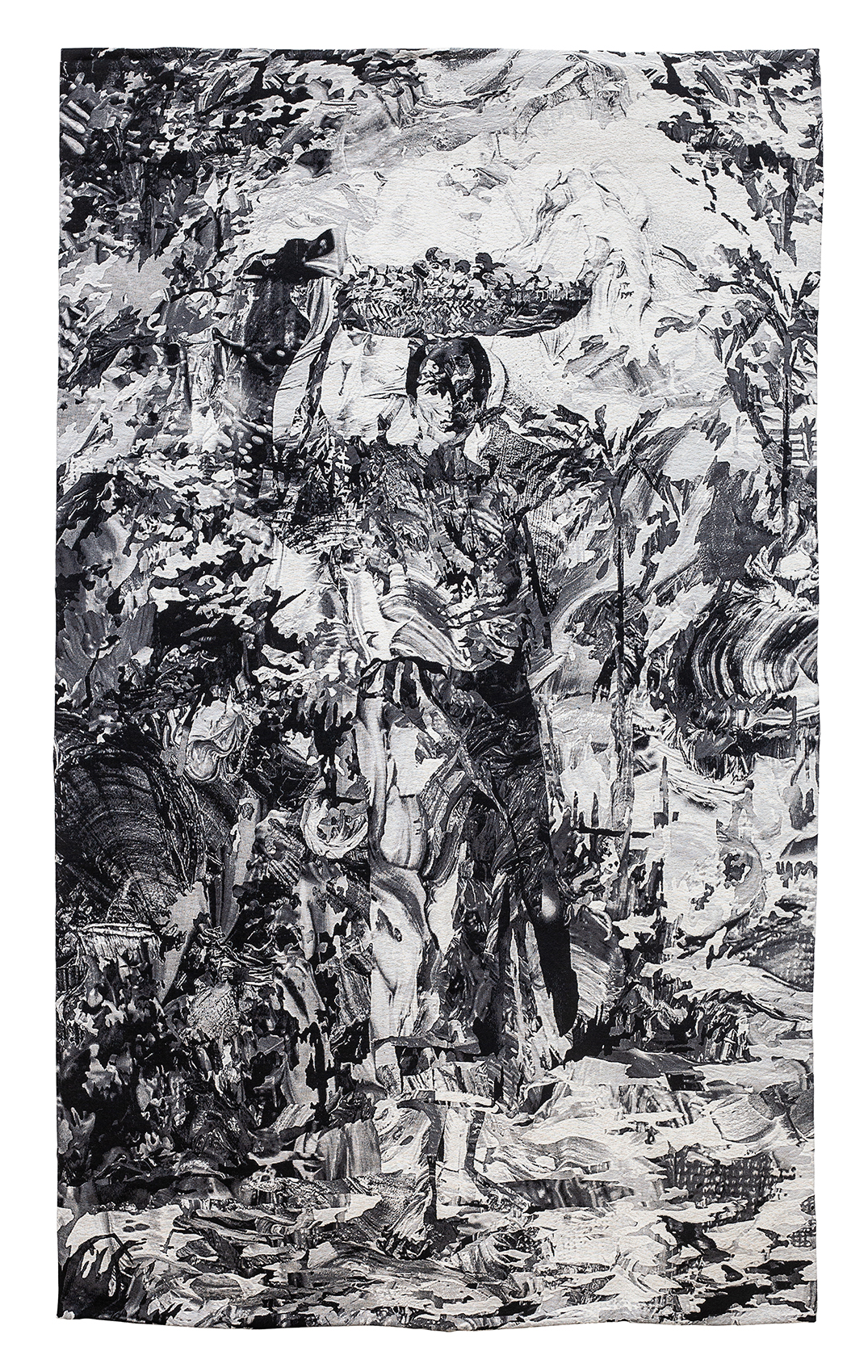

Eustaquio’s large-scale tapestries take historical paintings and digitally translate these into a black-and-white woven image. After La Vendedora de Lanzones appropriates the 1875 painting La vendedora de lanzones by the canonical Filipino painter Félix Resurrección Hidalgo (1855-1913). Resurrección Hidalgo is acknowledged as one of the greatest Filipino painters of the 19th century for his mastery of traditional European oil painting. However, Eustaquio deconstructs such classical portraits of pastoral life into woven paint strokes, and therefore asks the viewer to recontextualize not only the medium but the imagery and historical relevance of the painting.

“I have found working with fibers and textiles emancipating. In a sense I feel that whatever form these threads and fabrics take not only call to mind their contexts and stories, but also pull the community of people who produce them into my space of work… My attempt here is to throw my arms wide open. I wanted to create a riot, embracing the varying sums of the journey, of the emporium, as it has hurtles through time and space, along with the suggestion of everything it has gained and shed.” – Patricia Perez Eustaquio

An Unraveling (Conversation Among Ruins, After Amorsolo) appropriates the 1948 painting Portrait of a Lady in a Terno (also known as Maiden in a Flower Garden) by canonical Filipino painter Fernando Amorsolo (1892-1972). Known as the "Grand Old Man of Philippine Art," Amorsolo remains celebrated for his luminous oil paintings that idealized Filipino culture, rendered in a characteristically European medium and style. However, Eustaquio deconstructs such classical portraits of pastoral life into woven paint strokes, and therefore asks the viewer to recontextualize not only the medium but the imagery and historical relevance of the painting.

“I have found working with fibers and textiles emancipating. In a sense I feel that whatever form these threads and fabrics take not only call to mind their contexts and stories, but also pull the community of people who produce them into my space of work… My attempt here is to throw my arms wide open. I wanted to create a riot, embracing the varying sums of the journey, of the emporium, as it has hurtles through time and space, along with the suggestion of everything it has gained and shed.” – Patricia Perez Eustaquio

For her Archipelago series, Eustaquio assembled an archive of “paint-as-readymade” by developing a lexicon of brushstrokes that she photographed and digitized. These motifs, enlarged and printed on canvas, were then embellished with hand-drawn graphite and precious gold and silver leaf, transforming the abstract gestures of the brushstrokes from mere objects into subjects. Says the artist, the black and white palette serves to “remove projections and history”. Meanwhile the title, Archipelago, reveals the subject to be the Philippines, asserting centrality for her homeland.

“I have found working with fibers and textiles emancipating. In a sense I feel that whatever form these threads and fabrics take not only call to mind their contexts and stories, but also pull the community of people who produce them into my space of work… My attempt here is to throw my arms wide open. I wanted to create a riot, embracing the varying sums of the journey, of the emporium, as it has hurtles through time and space, along with the suggestion of everything it has gained and shed.” – Patricia Perez Eustaquio