About

As Clear as Color

Art history and criticism tends to preempt the experience with the wonder called art. As the discipline names and describes art with authority, the feeling for its sensuous, vital form tends to give way to programmed understanding. This can be sharply observed when “abstract” configurations are explained away on behalf of the viewer who oftentimes is speechless or clueless before some thing that bears no resemblance to so-called reality or alludes to no reference in the world, memory, or imagination. In a way, the earnest, though mystified, viewer is left with only the object and its history and criticism. The sensing body disappears amid the generous gesture of abstraction.

There is thus a need to recover that chance to engage with abstraction, without the pressure, or even the prior burden, of getting “it” and getting it “right.” The first solo exhibition of Leo Valledor in Manila offers an occasion. Certain ciphers quickly come to the fore to frame this moment: that Valledor, who practiced in California and New York, has Filipino roots and that his abstraction comes from the hard-edge minimalist lineage. The artist and his art may be conveniently decoded via this shorthand at the outset.

But we can be more patient. We can spend more time with Valledor, his studies, and his paintings; and try to foil how a programmed understanding might take over what should be a heady experience.

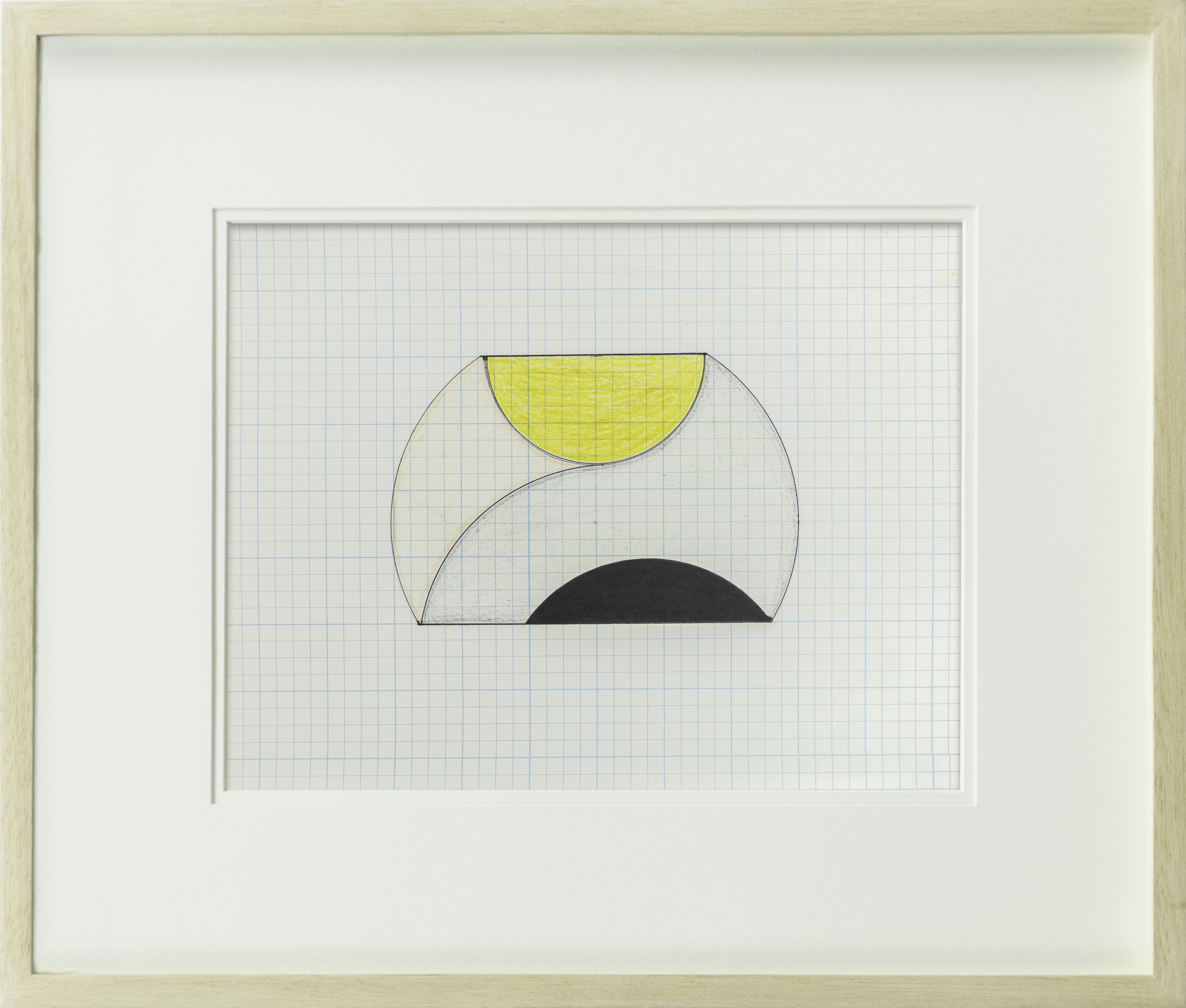

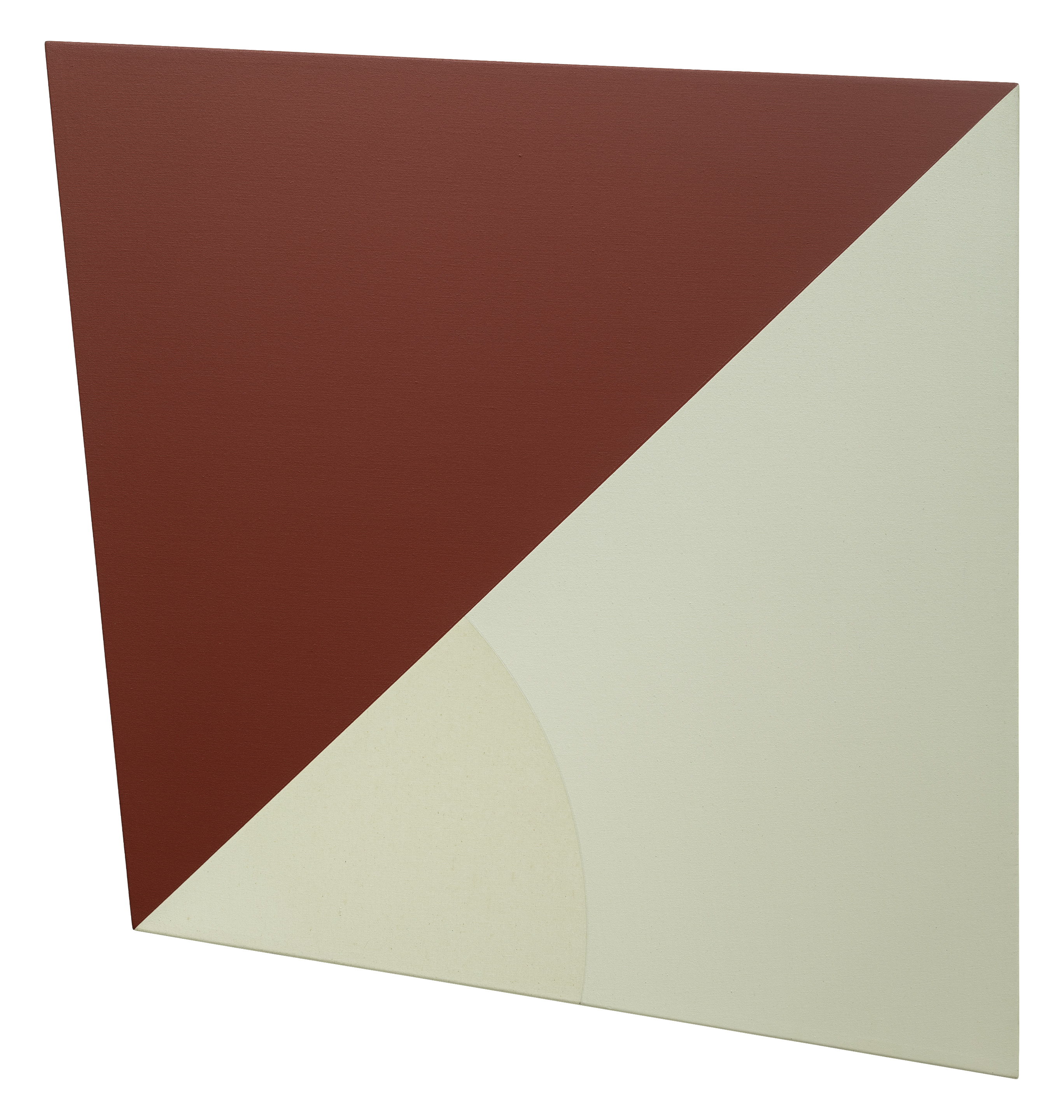

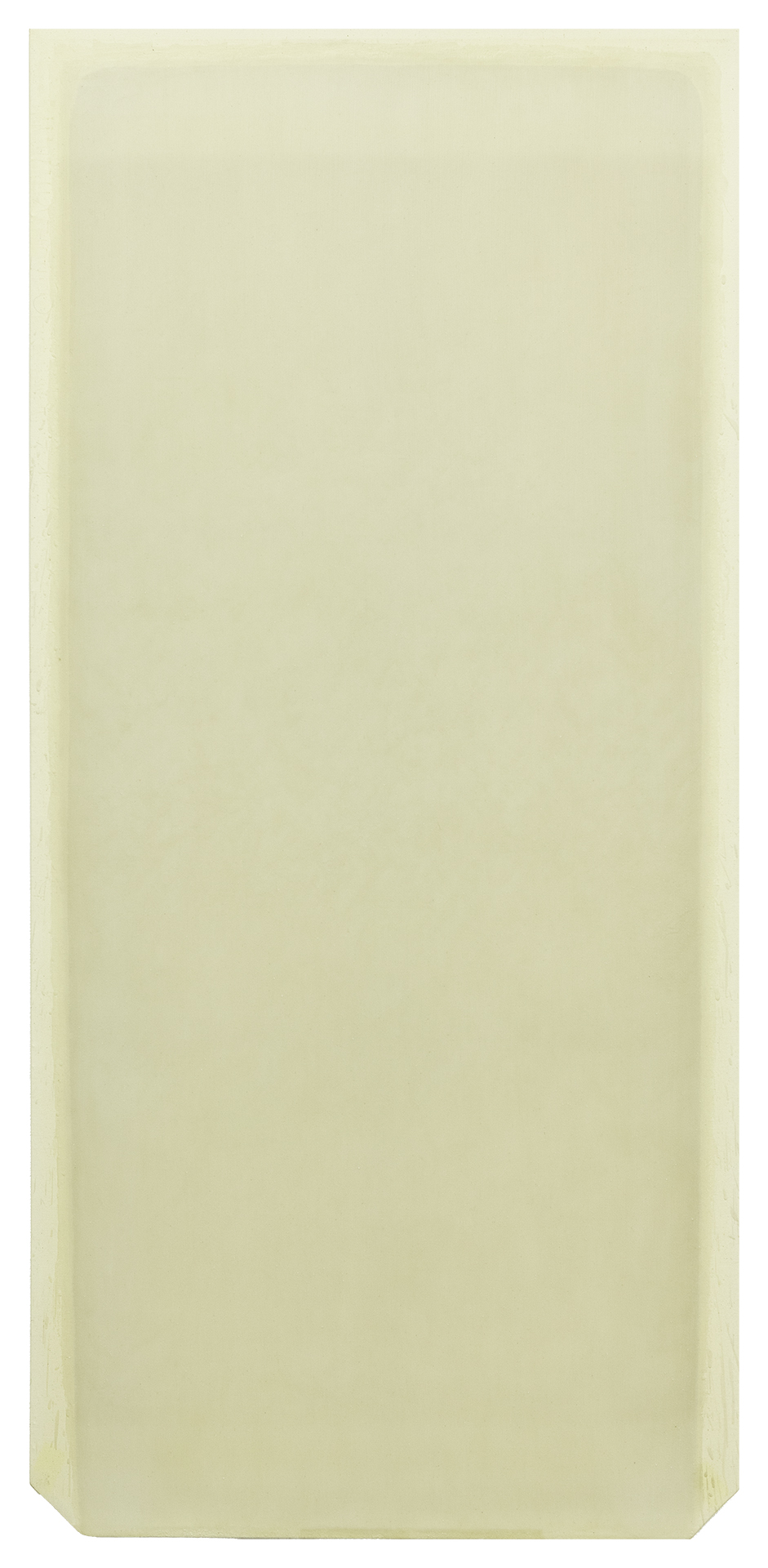

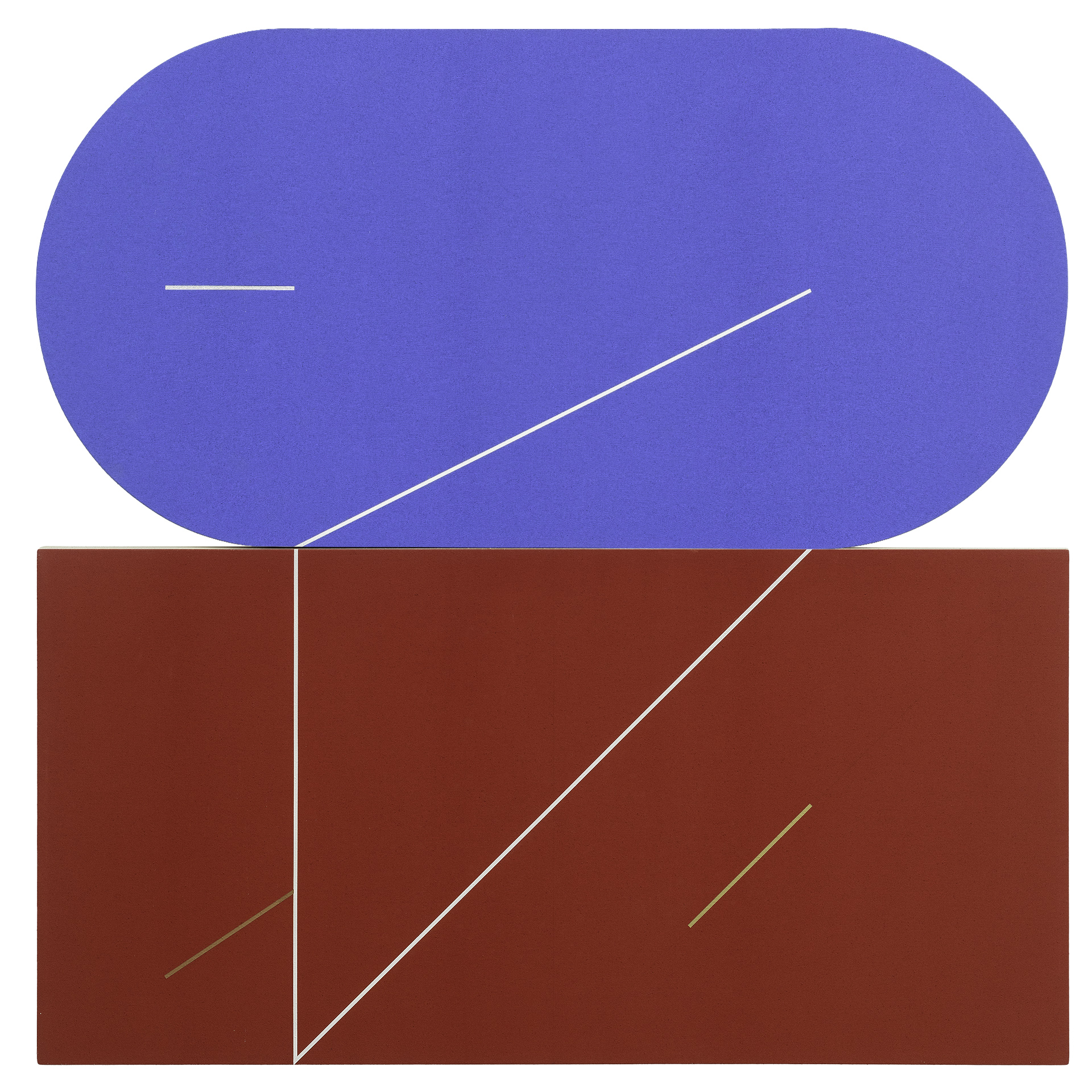

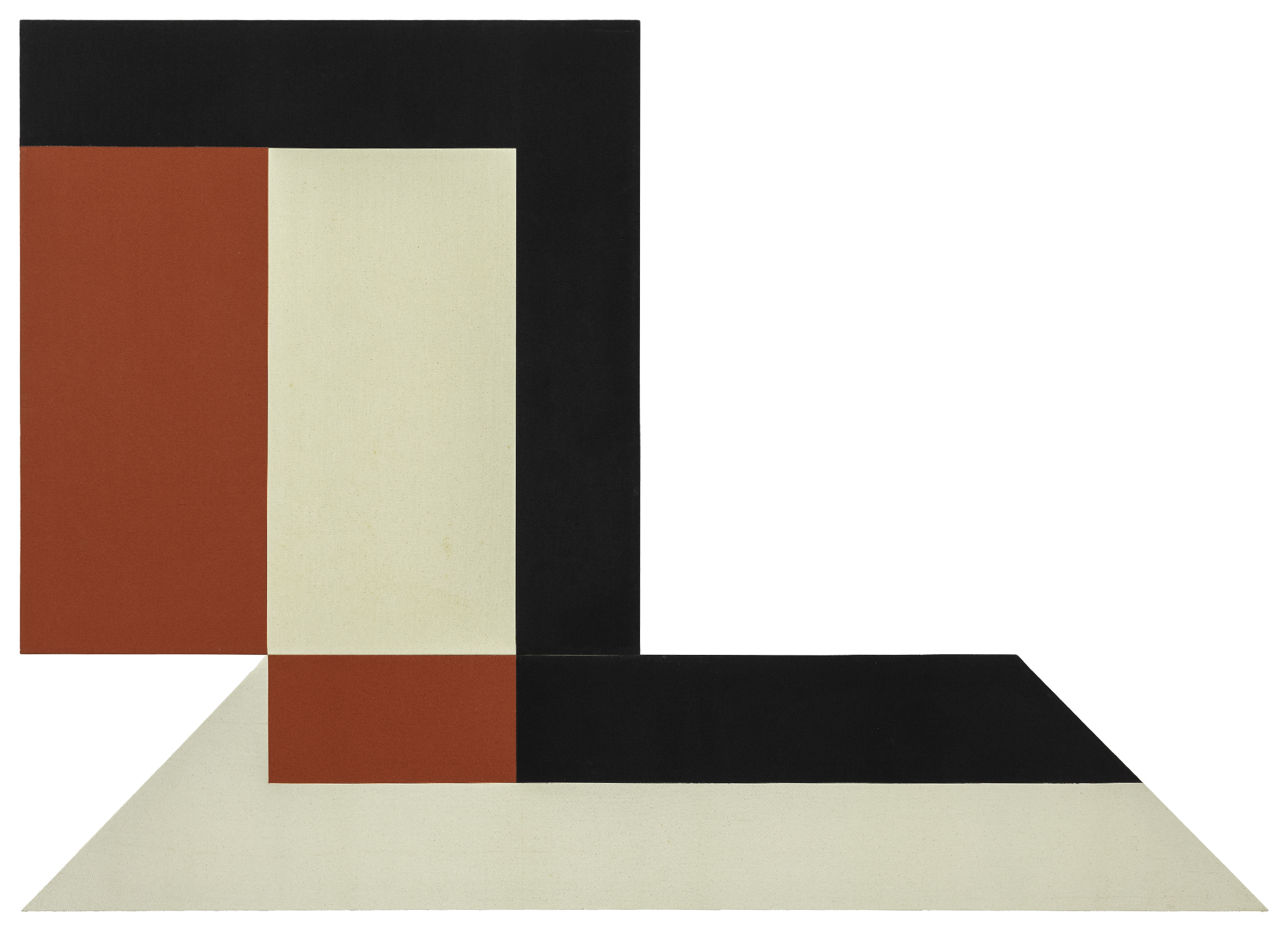

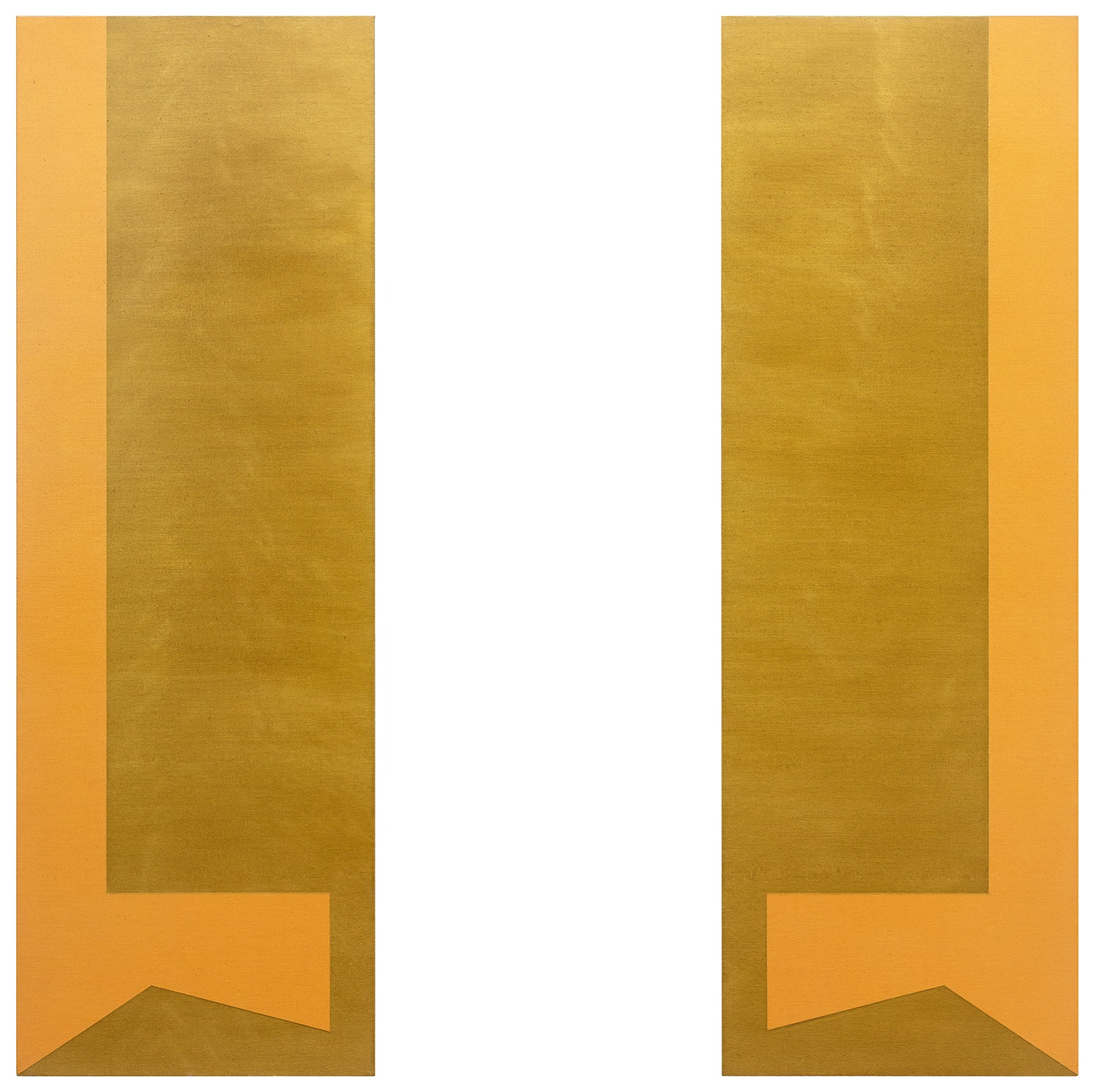

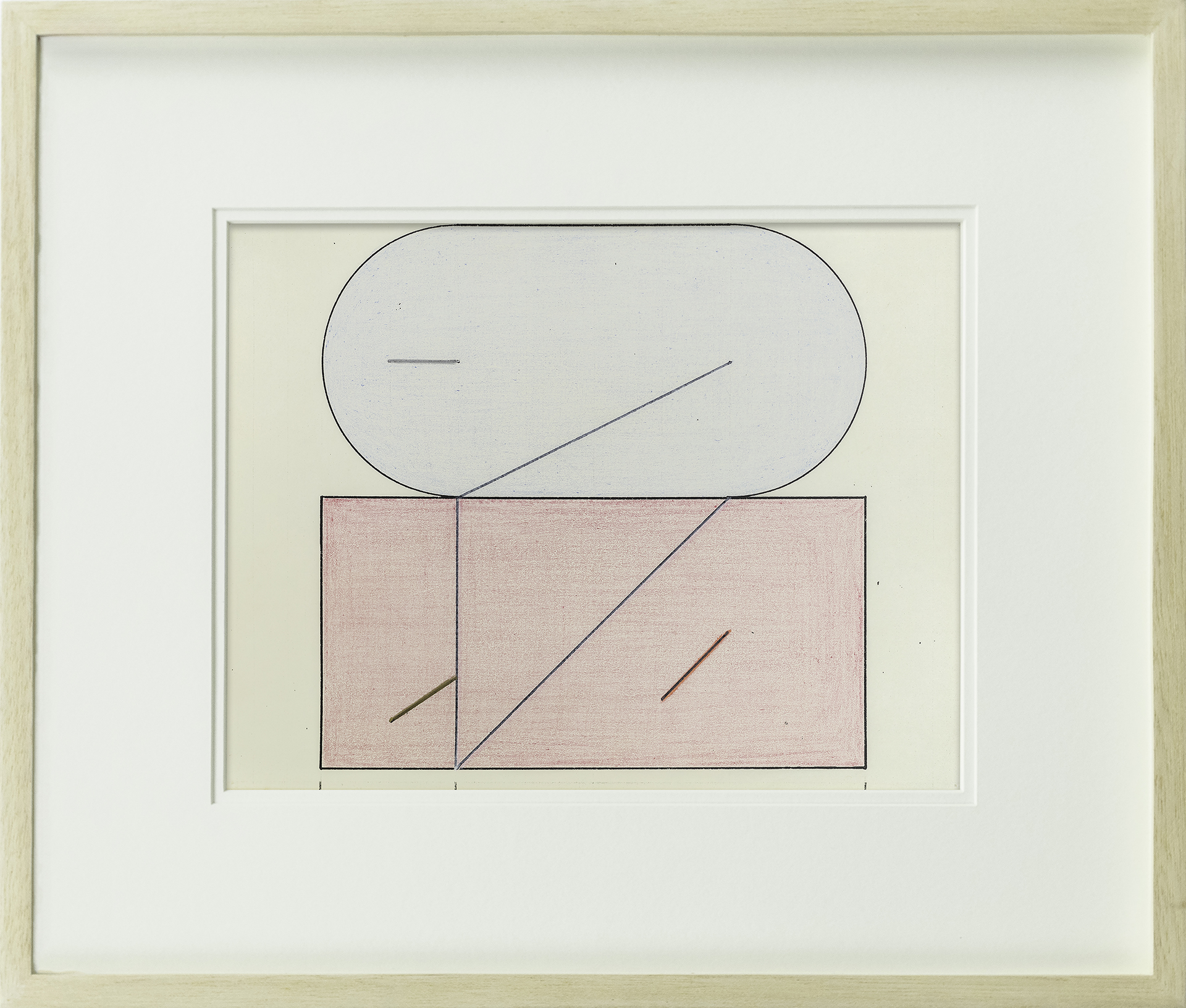

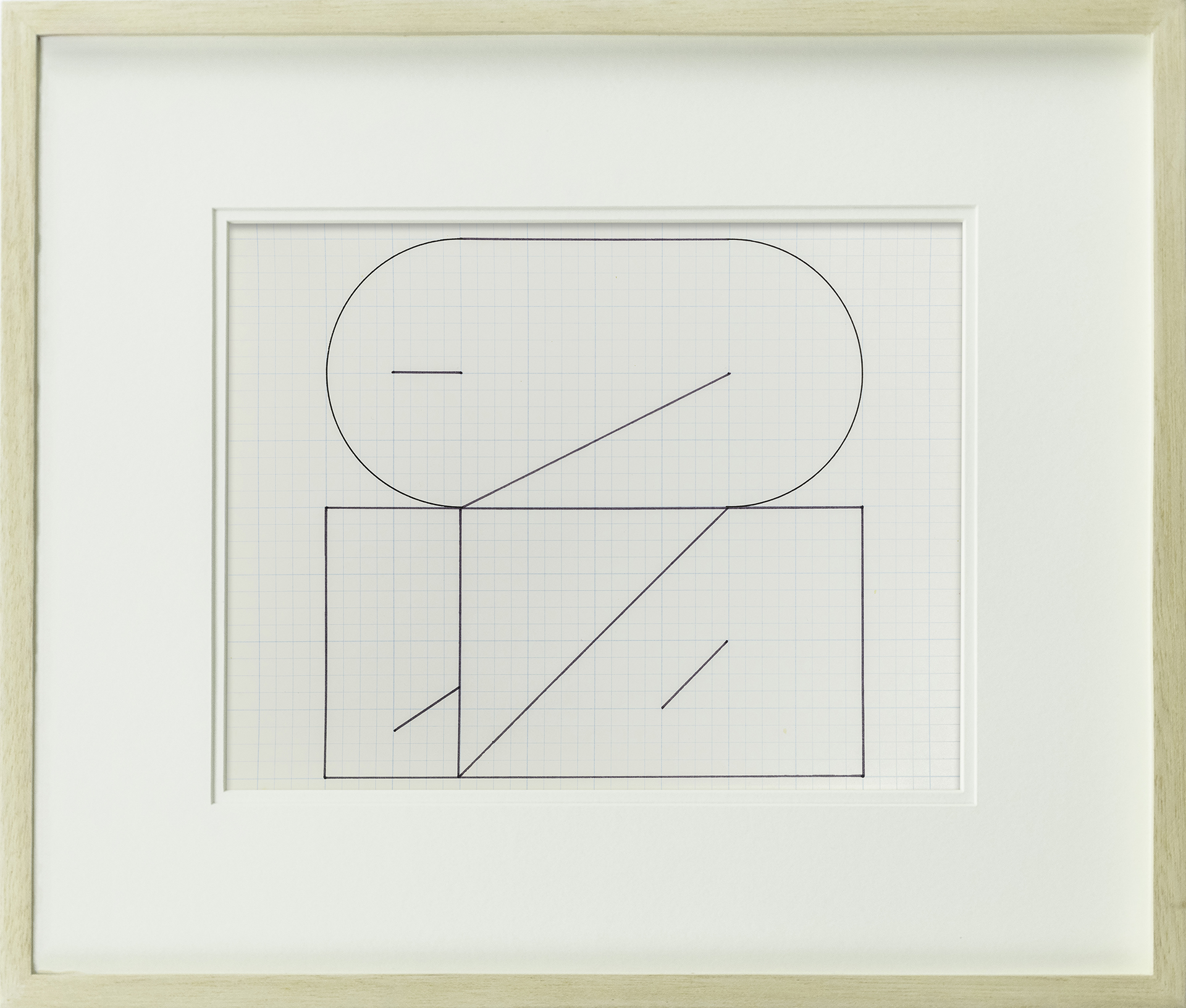

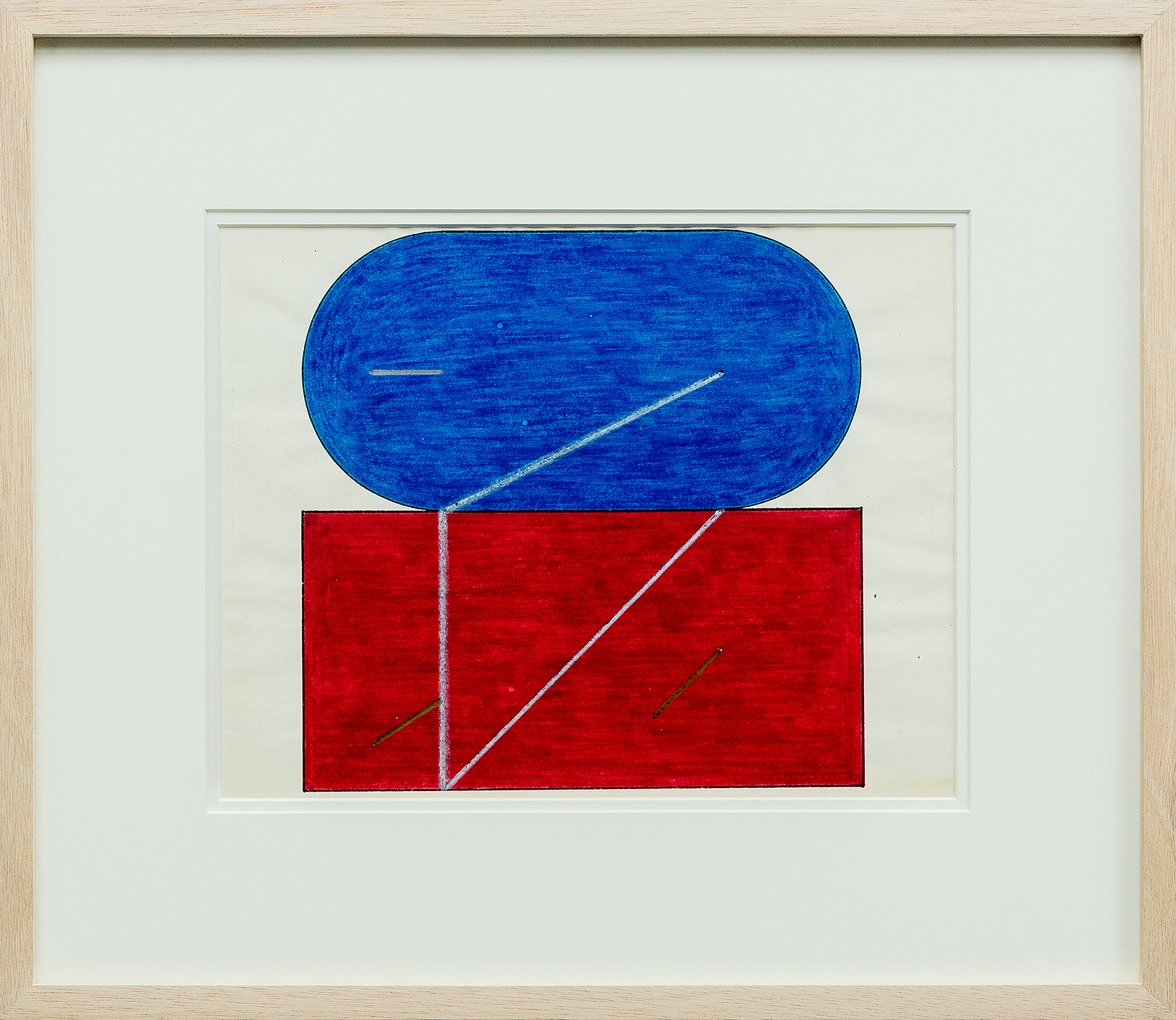

We see highly finessed canvases of almost pure color, organized in terms of geometric fields. They are very nearly flat, with barely a tone to indicate an illusion of dimension, denying the lyricism of gradation that validates skill or simply the realism that gives pleasure or the assurance of recognition. Though they are seemingly flat, they actually dissemble, making us ask if the color is the very support of the painting, or if it is, in fact, the layer of painting. Where is the medium here? And how does the paint work? The stature of painting may be betrayed by drips on the margins, index of material life beyond the control of even the most assiduous artist, or by a slight shift in the hue of the dominant palette. Color is a kind of all-over sublimation; and yet it is a clearing as well, a refuge in an existing— or another— ecology.

These canvases are not typical; they are shaped canvases containing patterns, their tectonic integrities tested by how they are made to barely touch each other. The shapes distract us: they draw our attention away from the expected “content” of the painting, if such content were a binary to its “form.” To the degree that the shapes dwell in our senses, they become vectors of visual interest themselves, assuming the status as both support and the totality of the art itself. And because the shapes achieve relative autonomy, the enterprise of painting ceases to pertain solely to representation. Painting becomes object, and also effect.

Upon closer reading of the stimuli playing out across the paintings, which consist of lavish geometries and inscriptions of line, fulsome in their physicality, we are also struck by the seams at which the planes find intimacy. These edges are delicate and severe, but they mark the suture, or the facture, of painterliness, at the same time that they enable the continuum, too, of abstraction, as a possible infinity or, at the very least, an instinct for the expansive. These edges are intervals as if they were for breathing, or meant to disrupt formalism, or to hold out an opportunity to improvise as in jazz or beat poetry. The latter seeded the sensorium of Valledor in the United States in the Fillmore District in the fifties and in Manhattan with the Park Place Gallery coterie in the sixties.

Abstractionists of the minimalist bent like Ellsworth Kelly and Donald Judd put their faith firmly in the agency of the body to intuit the world. Their thoughts on this are instructive, as we more closely acquaint ourselves with Valledor’s impulse. Kelly asks and answers: “What is the world? It’s what your eyes see. But as you move, everything changes. If you move a little, the whole world adjusts.” The coordination of the eyes and the limbs within the world is the awareness of aroundness: the wholeness that adjusts, the worldly that changes, the everything that moves a little.

The intensity of this agency of the body makes the visual possible and of interest. This body diligently, persistently, even obsessively works through conceiving and discerning, not in the programmatic way, but rather in a performative, tropic affection. As Judd would encourage: “You have to look and understand, both. In looking you understand; it’s more than you can describe. You look and think, and look and think, until it makes sense, becomes interesting.” Judd extends this investment in the human capacity to actually ordain time and space altogether. For him, they are not givens, and that it is in abstraction that they can be invented: “Time and space can be made and don’t have to be found like stars in the sky or rocks on a hillside.” Time and space can be had by looking and thinking in trance-like repetition until a tricky world transpires. As Valledor himself reveals: “By four-dimensional color I mean the notion that it exists within time. And I have this idea about time being part of all these ambiguities that we see in dimensions, like the idea that you read a line two-dimensionally and the difference in [if] that line [were] coming straight toward you as a point. I feel that the difference in that is time.”

What does this all mean in our effort to belong to Valledor’s art, to gain a measure of it from, let us say, the site of the Philippines? It may be argued that abstraction, in fact, had frustrated the default desire for the “identity” assigned to the artist, that it was able to delay the recognition of his identity as Filipino in the former empire of the United States that had colonized the Philippines. This delay, like the interval in his paintings, releases the migrant or diasporic artist from convenient multicultural capture and simultaneously invests him with a less legible, but nevertheless salient, post-colonial and cosmopolitan persona. Valledor’s abstractions in their time were able to diffuse the appearances of identity and in the same breath resist the discriminations stemming from systemic racism, which surely included the occlusion of his robust practice in the narrative of art history. As an artist with a Philippine heritage doing abstraction in the United States, Valledor eluded easy identification and might have invited erasure. That said, he would render the said abstraction political as he challenged how the apparatus of representation would elide or confine him, the very same condition that had made him complex as an at once, and irreducibly so, Filipino-American and abstractionist.

If Valledor complicates the purity of the painting form by his hints at tonality and vibration, the contingency of acrylic, and the carpentry of his canvases, so does his quest for idealized purity make sense only in relation to the struggle with objectification in both non-objective painting and racialized, therefore objectifying, society. In this process, Valledor would anticipate a potential civic space as shapes open up and pigment bleeds to flesh out the spectrum of spatiality that makes the social matter— or to instantiate the social itself through spatiality. To Valledor, a citizen of the diaspora, this allegorical, because ethical, space in abstraction was fundamental. It made quite sure that his subjectivity did not become too obvious to be routinely hailed, poised as it was to stage the difficult demands of society and the syncopated sensibility of the artist to stake out another ground, or clearing of color, or overall shapely rhythm.

Words by Patrick Flores, courtesy the Estate of Leo Valledor

¹ Richard Shiff, Richard Shiff: Writing After Art; Essays on Modern and Contemporary Artists (New York: David Zwirner Books, 2023), 301.

² Ibid, 273

³ Ibid, 287

⁴ https://plantingrice.com/content/leo-valledor-painting-interview-david-bourdon-new-york-november-1965-2008

Leo Valledor (b. 1936 - d. 1989, San Francisco, USA) was a San Francisco-born, New York- based abstractionist and founding member of downtown Manhattan’s trailblazing Park Place Gallery, an artist collective and exhibition venue founded by ten emerging artists, many of whom are now recognized as among the most influential Modernists in American history.

Valledor’s strong understanding of color optics, geometric planes and dimensional illusion combined with shaped canvases to engage the viewing space in powerful ways. Influenced by luminaries such as Ellsworth Kelly and Frank Stella, Valledor’s work resonated with the color- field and minimalist aesthetics, distinguished by his inventive manipulation of space, shape, and color.

Valledor’s artistic legacy continues to reverberate through collections nationwide, with works in prominent collections including The Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Leo Valledor’s work has been exhibited at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Daniel Weinberg Gallery, M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, and the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art.

Video

Works

SPI_LEOV055

Sold as a set of 2 (Untitled painting and drawing)

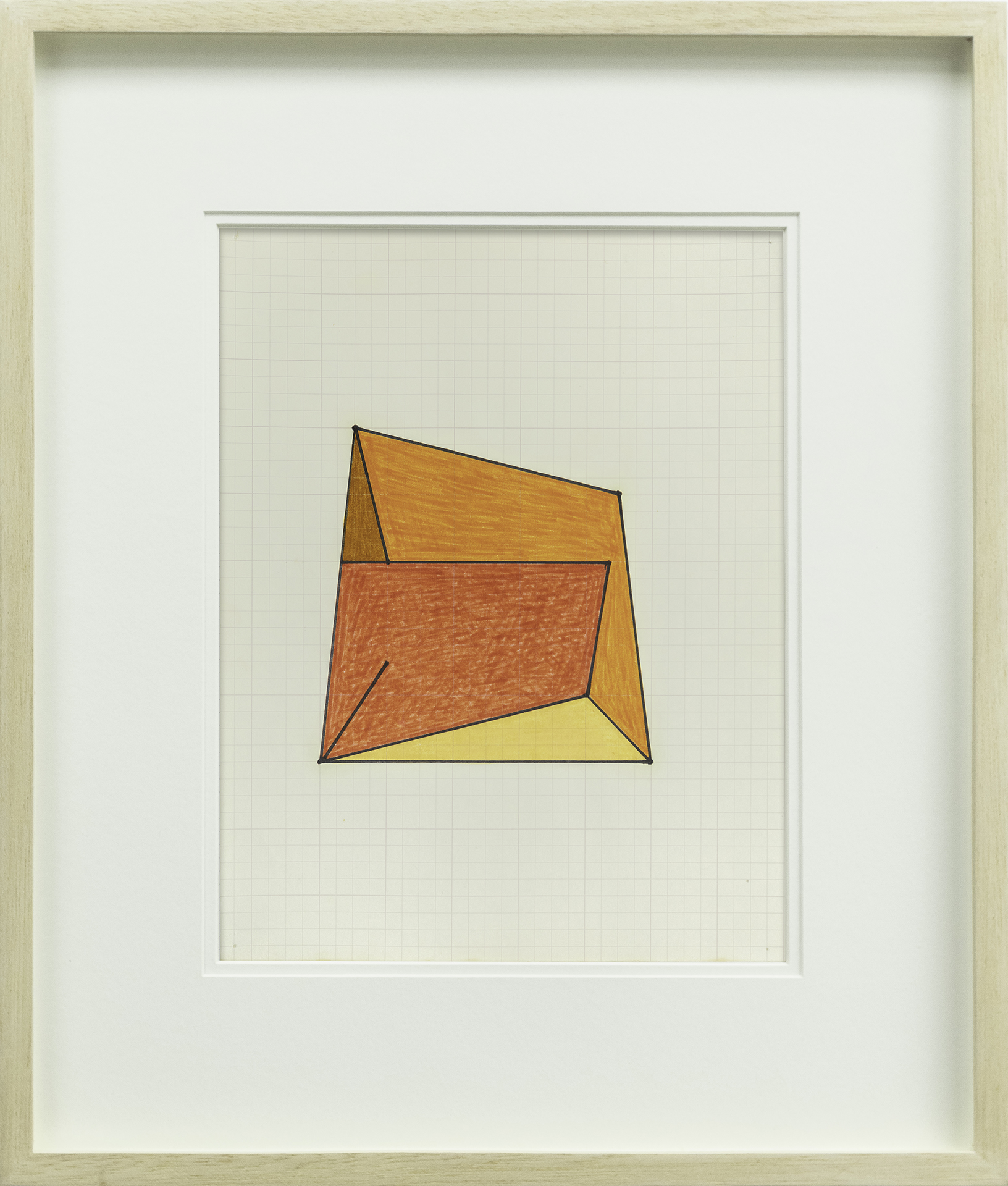

Sold as a set of 2 (Untitled painting and drawing)

sold as a set of 2 (Supriolism painting and the drawing)