Land Poetics

Dina Gadia

Silverlens, Manila

About

Not-Nostalgia and Two Scholia

Words by Raymond de Borja

In Land Poetics, Dina Gadia supplants her usual clever juxtapositions and shrewd wit with possibly the closest one can get to her works with depth of feeling. In contrast with her recurring semiotic preoccupations – with diagrams and floating signifiers (Navigating the Abstract, 2020), with gestures and affective states wrenched then recontextualized from pulp and comics material (Situations Amongst the Furnishings, 2017 and Adaptable to New Redundancies, 2013) – the images in Land Poetics are cut out and reappropriated with a starkness of style and simplicity that approaches pure punctum and indeterminacy.

“Very often,” Roland Barthes says, “the punctum is a detail, i.e. a partial object.” The thick black line moving down from the top side of the canvas then at a slight diagonal to rest on the text in Land Poetics (Quality Container) is in fact “the window frame of the door of a truck I once saw on EDSA,” Gadia shares in conversation, “the text reminding me of the many containers -- vases, drinking glass, glass bottles… -- that have haunted my collage works for many years.” The memory of that typeface on the truck door, first captured in a photograph, is then recalled here in paint, the red brushstroke carrying with it the quality one finds in urethane letterings on commercial vehicles.

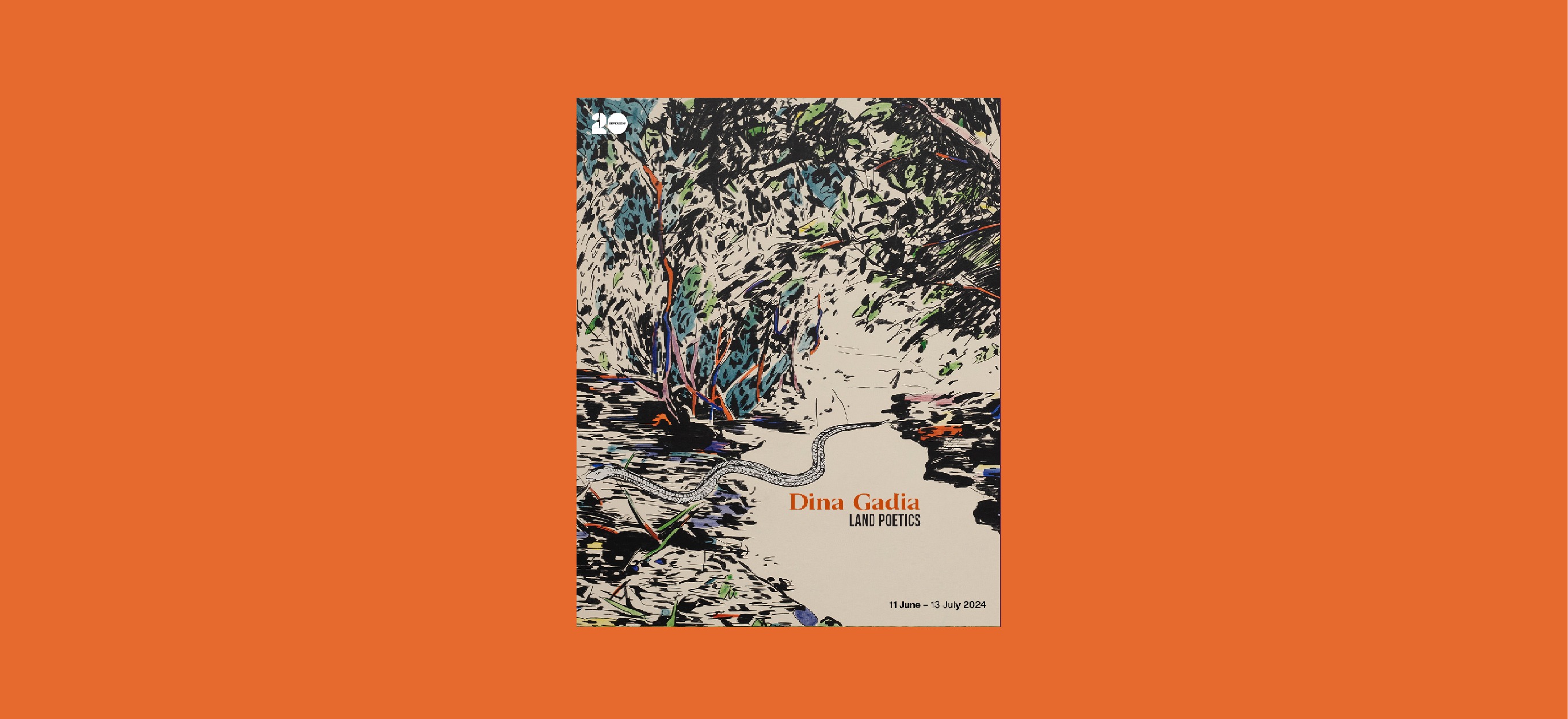

In Land Poetics (Encounters) and Trees, analog print technology is replicated with burst brushwork and acrylic wash, the technological and cost constraints of past printing technologies here become painterly signature, perhaps posing the questions: what happens when our mass of personal, cultural, documentary visual materials are passed through painting’s logic? What fields of discourse do they enter, do they open up?

But isn’t nostalgia by default an already suspect sentiment, lying on a spectrum which at one end, less hysterical and all-veneer, triggers our consumerist drives and on another, farther hysterical end, pure fanaticism, feeds our mass passion for fascist figures and tendencies, ways of life?

The garden, the one in Land Poetics (Encounters), bushy, seeming façade to a deeper woods, Gadia shares, is in fact the unkempt “playground near my childhood home in Anda, Pangasinan.” “This might look like a common palm tree, but it is not, it is called Silag and it bears small coconut-like fruit” she says of one of the tree images in Under One Constant. “This one here collaged with the bonsai is the flowering plant of a kamote.”

In Gadia nostalgia is, as Frederic Jameson had said writing about Walter Benjamin’s fascination for children’s books, “conscious of itself.” A nostalgia which like in Jameson, is borne out of some “remembered plenitude” but on the contrary, also, one that is neither satisfied nor dissatisfied with the present but sees the present as material and impulse to further map painting’s expanded field. Field explorations that are especially cogent as painting’s archive – its histories of factures, techniques, and aesthetic decisions – are sorted and tagged, statistically flattened to become the large universe of data for training generative AI models.

Perhaps the most allegorically-rich figure in all of Land Poetics is the snake found in Land Poetics (Encounters), slithering, or more accurately, floating on the leafy floor, it’s former physical cut-out studium not quite sinking to the ground it is reappropriated on. This snake is a stand-in for the actual snake, the many ones that Gadia encountered in her childhood playground. Specificity and detail, Gadia shares these stories and recalls them in her painterly sensibility, rescuing the images from the statistical universe of the studium to have them approach new meaningfulness in the generative spaces of the punctum.

And the expanded field that Land Poetics seems to be mapping, if one were to construct a Klein Group, as Rosalind Krauss did for sculpture’s expanded field (i.e. sculpture being not-Landscape, not-Architecture), or as George Baker did for photography (i.e. modern photography being not- Narrative, not-Stasis) is a field that reconciles and recuperates the personal from the contemporary cultural-historical; one finds in Land Poetics both signature wit and genuine depth of feeling, mapped out in a field that begins as its topological starting point the terrain that is marked not-nostalgia.

Scholium 1:

What binds the works in the show, other than painterly sensibility, is negative space. The only work where negative space is almost not featured is Land Poetics (A Collective View) which is a painting of clouds reappropriated from jeepney art. What are clouds, amorphous, if not themselves negative space? The white spaces here do not invite us to fill them. One can think of them as larger scale ligatures linking the pieces, while containing them, and continuing Gadia’s semiotic and textual impulses, haunting her works as would the negative space inside her quality containers.

Scholium 2:

Preparing to write the essay this morning, I printed draft number zero – a loose assemblage of notes, sentence-thoughts, and diagrams that will eventually become the essay. But I didn’t realize I had run out of black ink. So, of three pages of drafts, only two lines of texts were printed, off-center on two separate pages, and only because they were highlighted in green and written in white font. The first sentence said: “But we suspect nostalgia.” The second line of sentences is by Svetlana Boym, it said: “Somehow progress didn’t cure nostalgia but exacerbated it. Similarly, globalization encouraged stronger local attachments.”

Works Cited:

Baker, George. “Photography’s Expanded Field.” October, vol. 114, pp. 121–40. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2005

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida. Translated by Richard Howard. New York City, NY: Vintage Classics, 1993.

Boym, Svetlana. The Future of Nostalgia. New York City, NY: Basic Books, 2001

Jameson, Frederic. “Walter Benjamin or Nostalgia.” Salmagundi. No. 10/11 (Fall 1969 – Winter 1970), pp 52 – 68. Saratoga, NY: Skidmore College, 1970

Krauss, Rosalind. “Sculpture in the Expanded Field.” October, Vol. 9 (Spring, 1979), pp. 30 – 34. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1979

Installation Views

Works