About

An Air-conditioned Hell

Jay Bautista

Bread and Circuses, a solo exhibition by Alfredo Esquillo creatively adapts the theory of mass culture as social decay from the book of the same title by American author and theorist Patrick Brantlinger. The phrase Bread (panem) and Circuses (circenses) was first coined by Roman poet Juvenal, it was used by Brantlinger to summarize the eventual decline of heroism among the Romans after the Roman Republic cease to exist and the rise of dictatorial Roman Empire consequentially began. Applying Brantlinger’s study as an in-depth parallelism to current Philippine society, Esquillo points out two things that the Roman Emperor distracted the people by keeping the populace happy—a full stomach and staging huge spectacles at the plazas and coliseum. Esquillo vividly compares the Roman Empire to Philippine modern society dating back the 70s up to the current affairs influenced by television and social media—as we are witnessing disinformation and revision of history.

Through paintings, sculptures, and installations, Esquillo exactingly recreates, as he artistically essays recurring signs and symbols concurrent in both with politics, culture, and technology, in relation to misappropriated policies of our former and incumbent presidents. As we have been endowed by sheer short memory of the past, Esquillo assiduously reminds us, as his bespoke images haunt us, that unless we become more learned from our past, we cannot charter our destined future with hope.

As we prepare ourselves for a new elected leader, who will either be determined to get us out of the quagmire or further sink us deeper in the social quicksand, Esquillo situates the complex context we are collectively facing. He let us understand ourselves vis-à-vis the ongoing efforts to revise history that Martial Law did not happen. Esquillo’s critical artistic renderings, as well as his endowed political learnings, are similar to banging our heads to the walls desperately for the first time in order to make us realize our own misconceptions.

In Road Rage, Esquillo compares the Roman Empire with the morsels of oppression in Martial Law—as the distraction of chariot race with television during the 70s—were one and the same. Done in oil on canvas, Road Rage shows the comparison of spectacle of chariot racing to the imposing television shows as Marcos was always ministering on the boob tube.

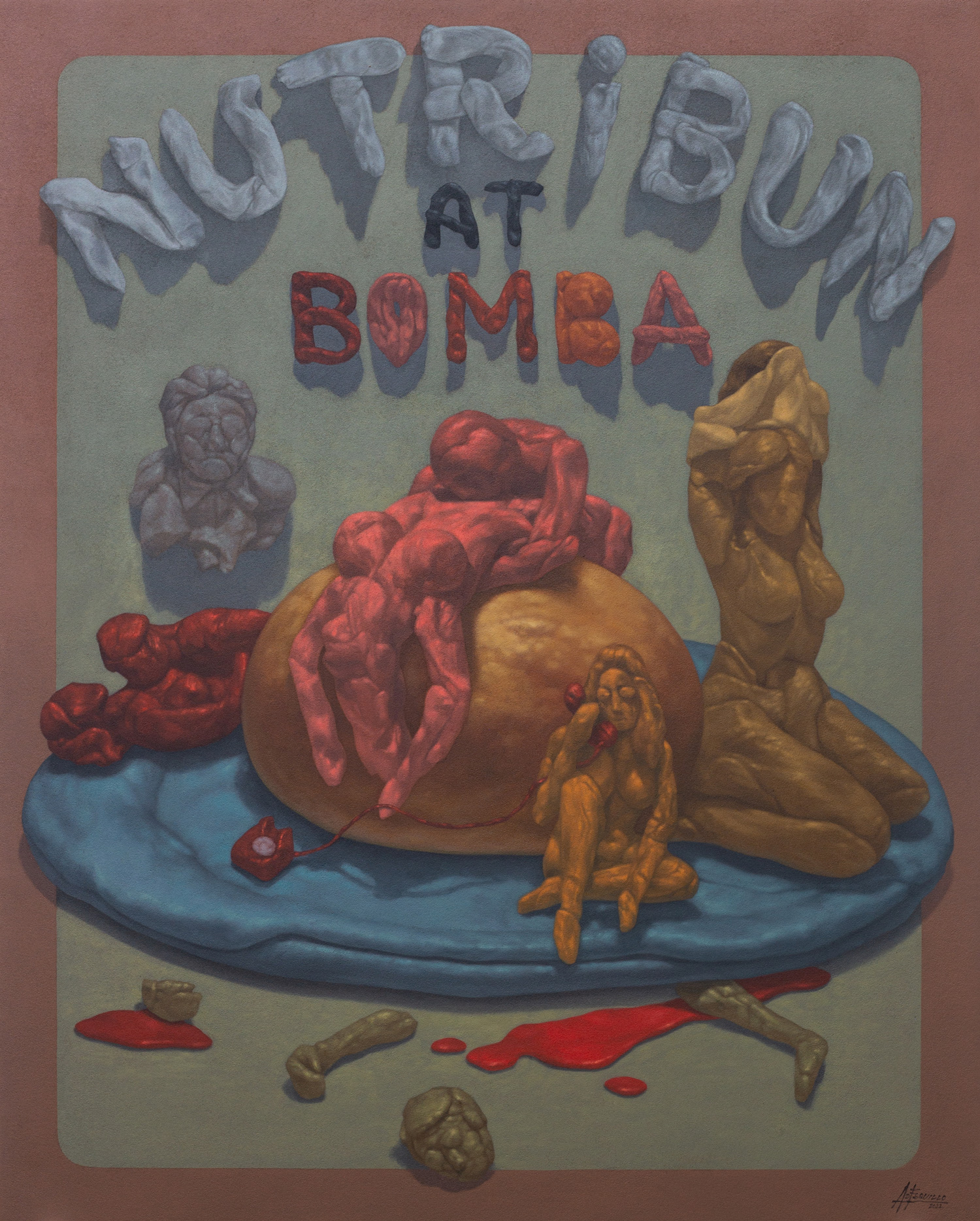

Continuing the Marcosian dictatorial tactic during the seventies is Nutribun at Bomba, Esquillo literally points out we were manipulated by the late dictator as he was feeding us while killing people and plundering the country.

Nutribun was a bread product designed by USAID which Marcos adopted to solve childhood malnutrition during the seventies. Nutribun grew its popularity since it was similar to pan de sal. There was a trade-off, however, as he was distributing the bread he was killing or abducting political activists heightened during this difficult time.

Using clay figures (as molded by Esquillo’s son, Yahsky Kayumanggi), Esquillo lambasts the First Lady for saturating us with gyrating women in experimental sex-oriented films at the same period she was squandering the people’s funds in the name of culture. She was also greedily shopping for art and shoes for her own personal consumption abroad.

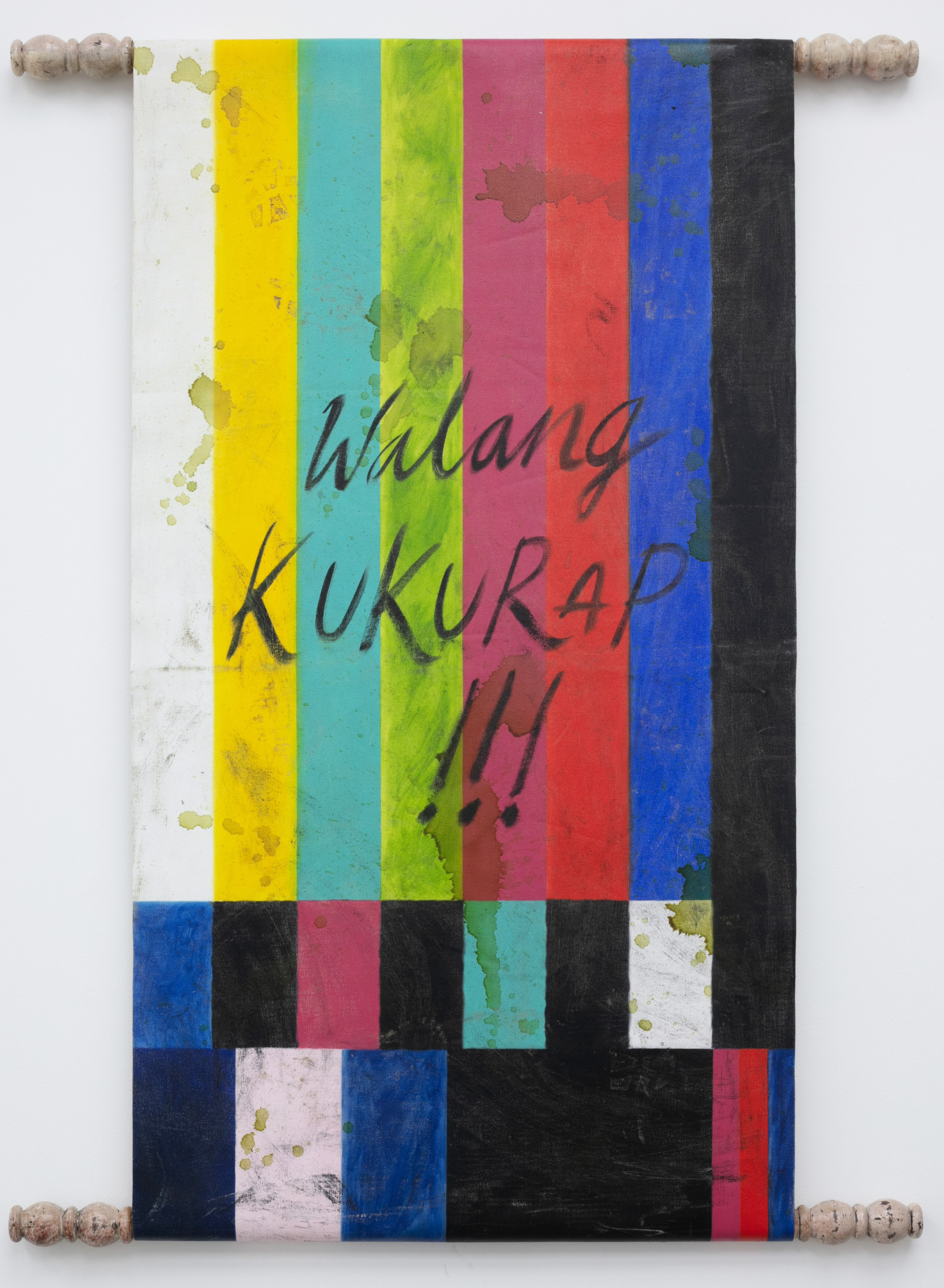

Continuing the discussion on the relationship of surfaces and the truth that was Marcosian is Walang Kukurap. During Martial Law, the color box was signal that an impending news is about to break—either Marcos was appearing or end of programming for the day—for the television station. Etched on the television screen is the warning Walang Kukurap calling us to be vigilant, as it could be a warning of bad things to come—manipulated vote count or an important announcement in Malacanang—enough to dupe the people. We have to guard against revision of history disguised by the beautiful images displayed but they are blindly brainwashing the viewers. The Marcoses were so beguiling that we were deceived that they were made to look good to the Philippines yet they grabbed the ownership of ABS-CBN from the Lopezes ABS-CBN further losing their rights to broadcast. This was again repeated when President Duterte did not renew their franchise to operate during their term.

Martial Law was all about attention and creating a seductive image even if the basis is economical corruption and moral theft. The First Lady was aware what seemed like Edifice Complex and created buildings and institutions everywhere. She took care of the overall-image in the name of art and culture, while President Marcos made it happen by committing human rights abuses and plundering us dry backed by his military ruling. That is what you have to understand with beauty, your attention is commandeered by shared hues. It disarms you and seduces you that things are desperately better for you. Even though it is not.

Well-versed in iconography, Esquillo sculpts Tree of Knowledge and Ignorance tackling how horrendous technology can make our lives artificially easier or can personally ruin us. Active in the social media platform, Esquillo knows this as it exists as requirements of present day yet he abhors qualified fake news as a complimentary given. As a responsible netizen, it is inevitable to shy away from social media as it has been source for fact-checking and acquired learning. Esquillo believes we just have to be vigilant in using digital application.

There is poetry in the way Esquillo engages in his contemporary images. In Decline and Fall of an iTallano Empire appears another parallel imagery of Roman Empire going down the drain—as seen in a toilet bowl stuffed with Marcos gold bars hidden behind. Esquillo is with full confidence in showing both declines as somewhat prophetic and of our own making.

In the manipulation of information, shit becomes gold. The literal throne of shit eventually becomes the throne of power.

In a no-holds-barred revelation, Dictatorial Insemination takes a serious pun at political dynasties. With an in-your-face sensation, Esquillo ponders creative reality that has happened at the back of our minds. A dictatorship consistency, a conjugal lineage that persist to haunt us now that their direct offspring are on the verge of continuing the leadership fallacy. Electing a son of a dictator is a slap in the face to those who were killed and disappeared during Martial Law. Only Esquillo can present the truth as if it is a repeating nightmare.

The Marcoses invented as it institutionalized a general culture of impunity delaying the justice of the poor. If one is poor, one is abused and taken for granted. As a people, we are still trying to establish who and what we are however, Marcos and Duterte are the fire who will strengthen to define us as a people.

Rounding up other basins of graft is Upon This Rock I Will Build My Bank which refers to the colossal deceit of public funds started with the Catholic Church dating back Spanish times. How the Catholic Church became evidently corrupt, using the Roman column to symbolize the Empire, Esquillo wittily morphs it into a church offertory donation box used during masses. One of Esquillo’s strengths is retracting what is Filipino in a post-colonial context.

Pompas Y Vanidades literally means “pomps and vanities” is a critique against myth-making and selfies. Through social media, Esquillo dwells on the death of criticality as it paves a new mass lifestyle based on clicked likes—a free for all plaza where anyone can build their own monuments of self-importance where fools can be kings and queens or the next Philippine President.

Being a Martial Law baby, Esquillo strikes back effectively how emperors and dictators manipulate the lives of their people—politics, media and culture—and controlled our destinies as a people and how we never learn from the mistakes of the past because we had our stomachs full and our eyes distracted.

Esquillo insinuates in us that we never learn and to move forward we must strive to reclaim the past—as we fought for freedom of expression, accountability, and transparency—in the streets and in the last national election.

Filipino artist Alfredo Esquillo’s (b. 1972) illustrious 25 years career in art scene includes dozens of major shows, numerous awards and participation in prestigious residency programs.

Equipped with a remarkable technical virtuosity in oil painting and continuing drive to experiment with his medium, his works have been avidly received in contemporary art. Esquillo delves in the periphery through the folk religious, the pre- colonial indigenous, and the fresh visual language of the young. He is known for his unique ability to profoundly combine imagery endowed with compelling realities and deep historical implication. He has brought in the idea of reinforcing deeper political and social bearings through combination of images. He prompts his audiences for self-reflection that recognizes the significance of human agency and spiritual discernment. Esquillo currently lives and works in Manila.

He is currently active in spearheading collaborative and community-based artist-led initiatives in the peripheries of the art scene.

Jay Bautista has written about contemporary Philippine art and for exhibition catalogues of Filipino artists. An award winning art blogger since 2008, he studied for an MA in Art History at the University of the Philippines Diliman. He was one of the writers for a monograph on Alfredo Esquillo in 2018.

Installation Views

Works

Video

Artist