Ryan Villamael

Bio

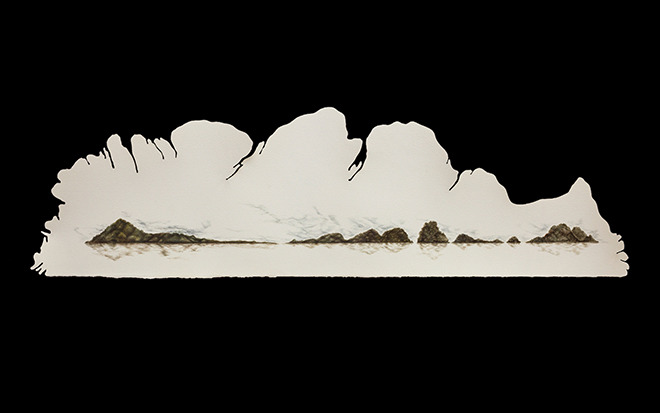

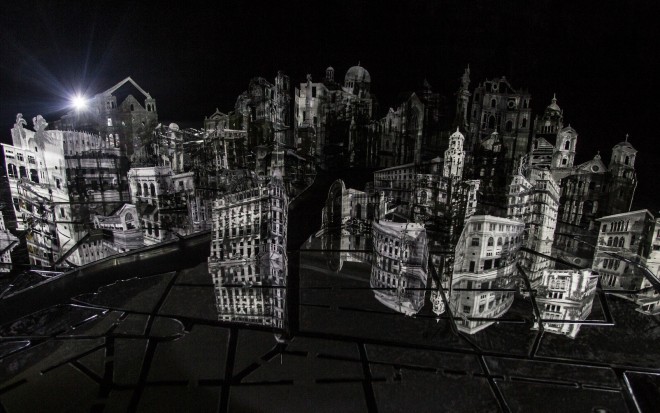

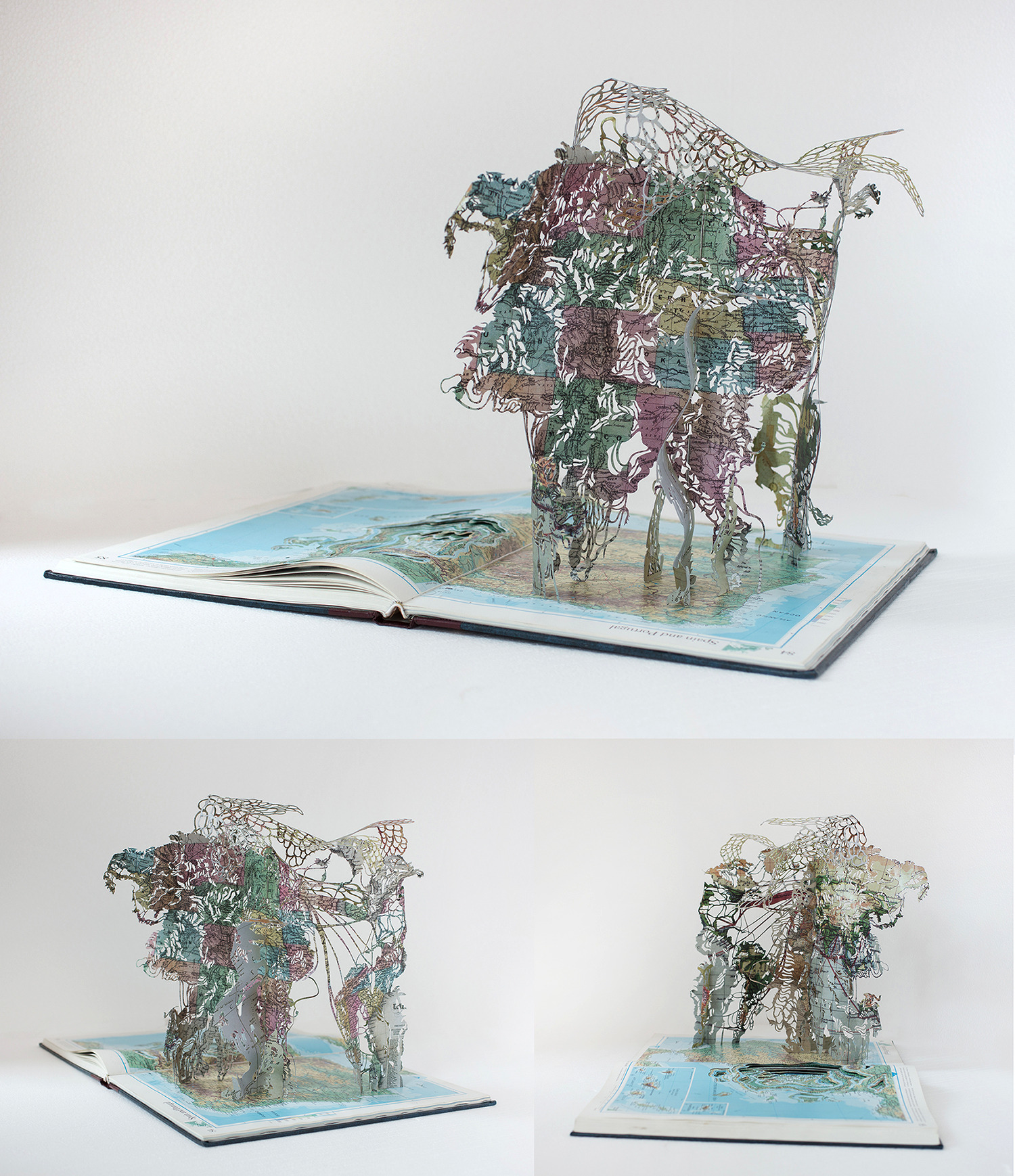

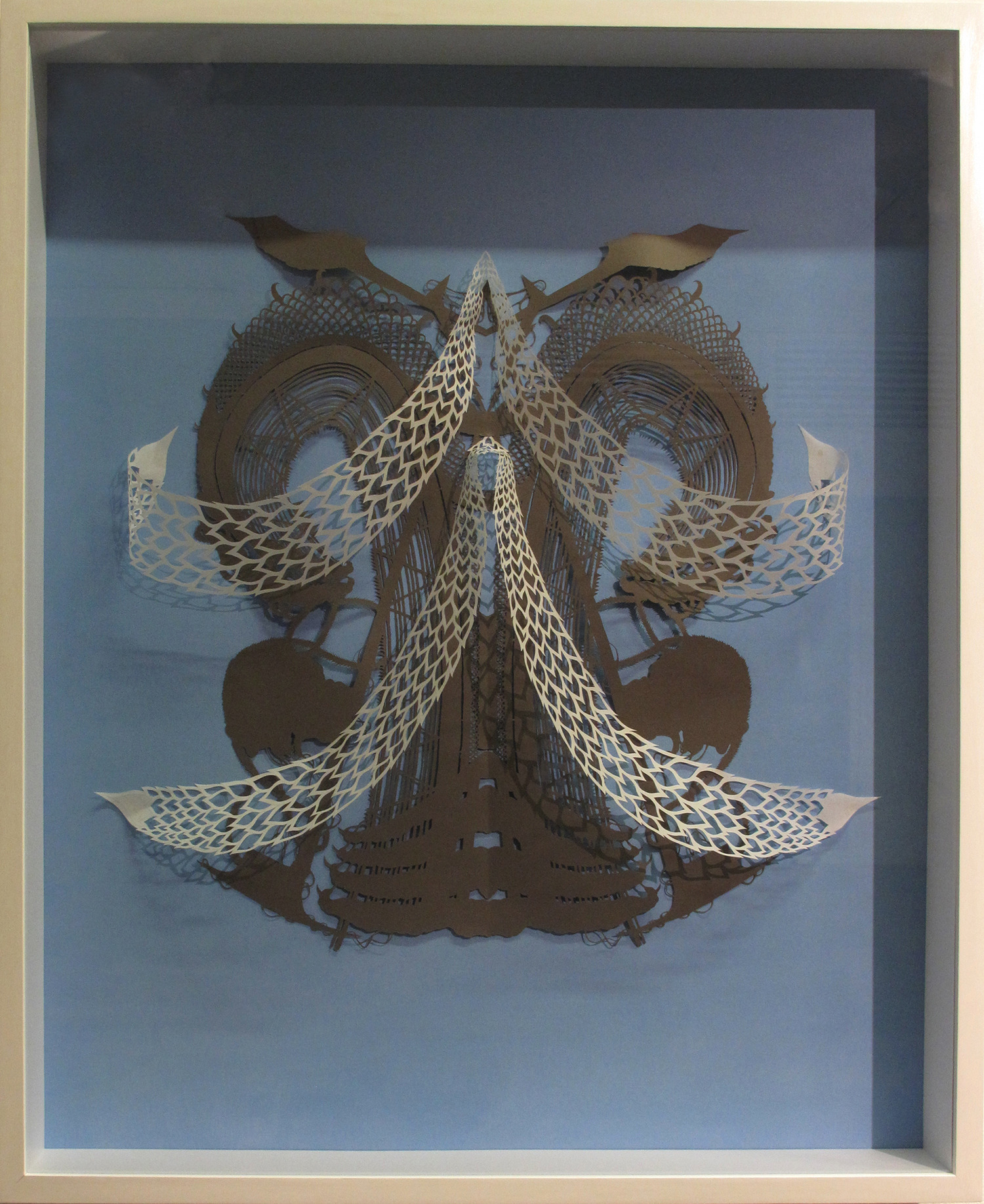

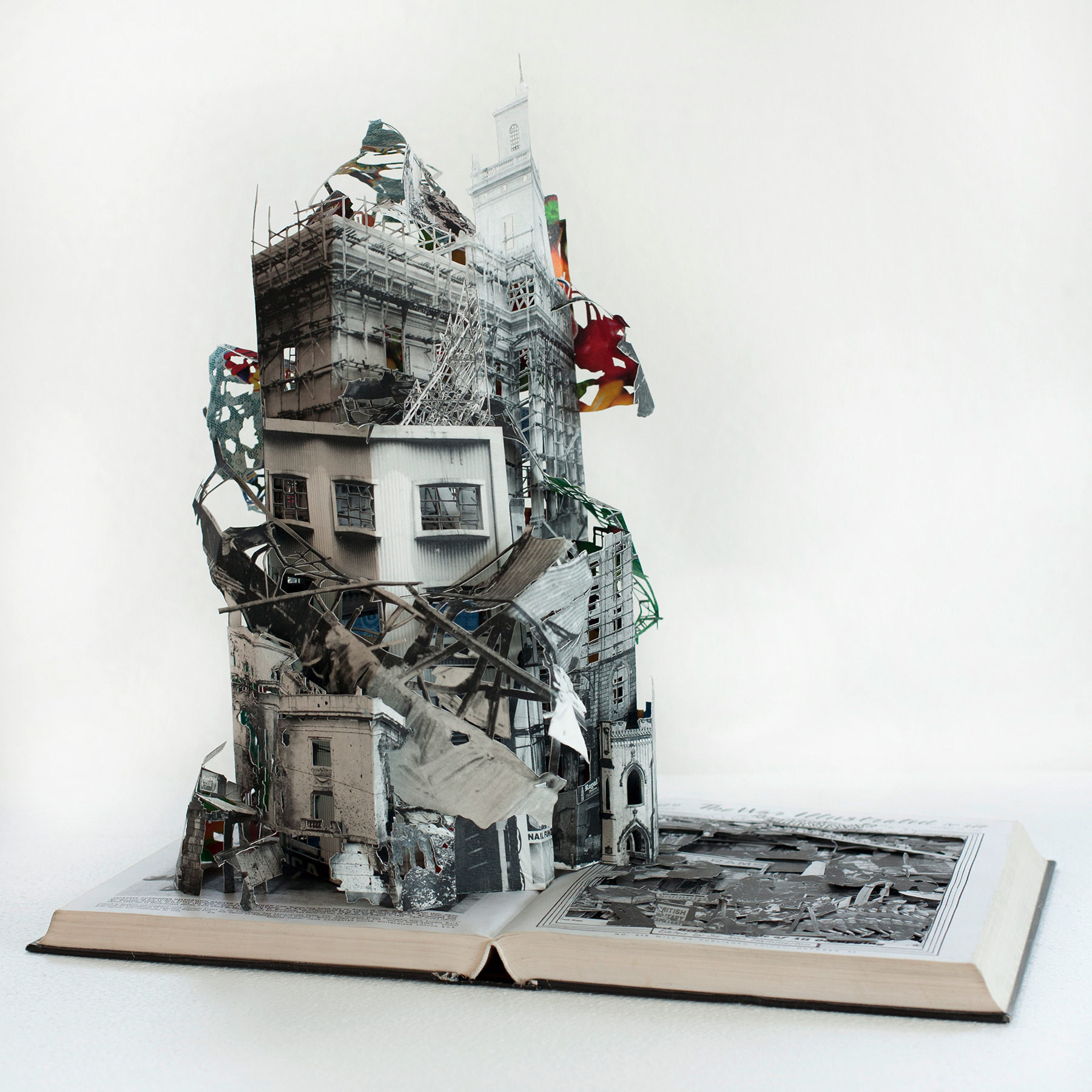

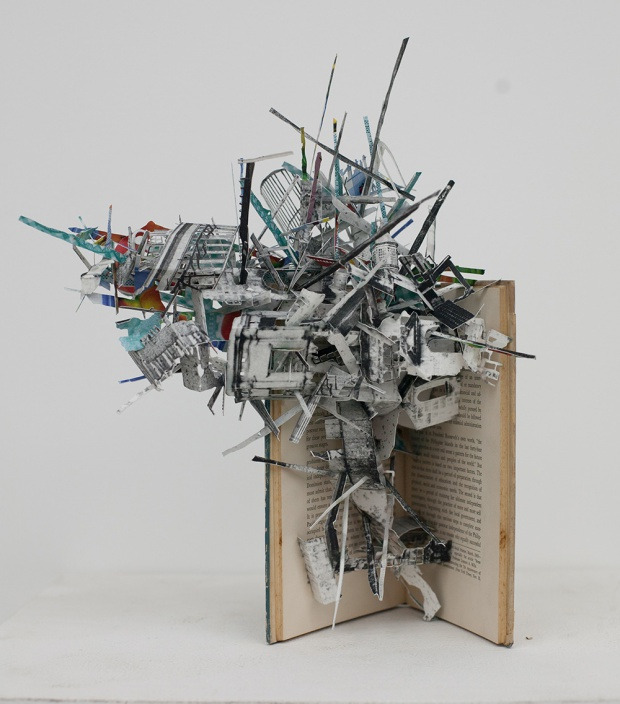

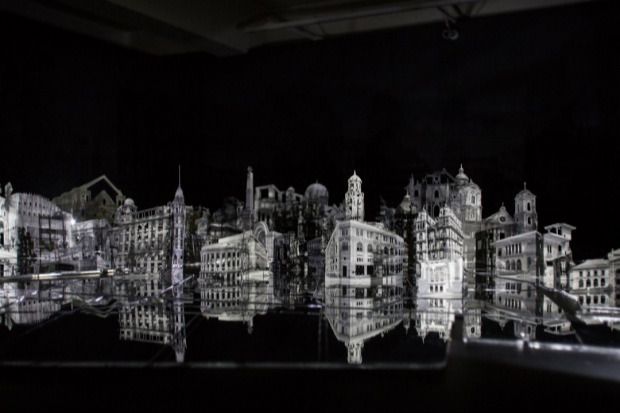

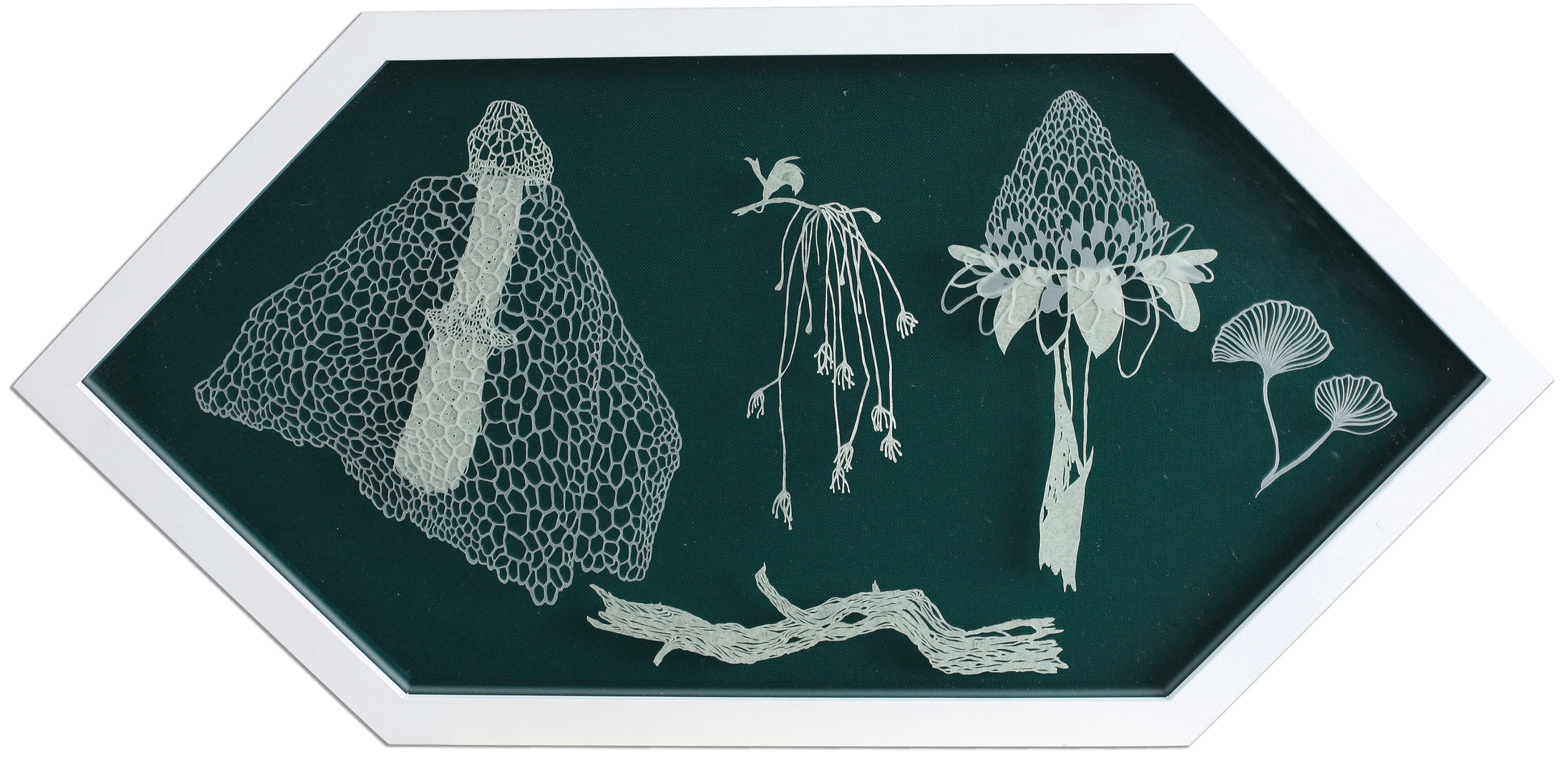

Ryan Villamael (b. 1987, Laguna Philippines; lives and works in Los Baños, Philippines) is an artist renowned for working with paper as a sculptural medium. With works ranging from stand-alone soft sculptures to large-scale pieces and immense installations, he has been exploring the themes, tensions, and trajectories of his chosen material for over a decade. Employing a rigorous dedication to technique and precision, Villamael uses the traditional Philippine art form of paper-cutting as a way to mediate and meditate upon history, collective memory, and the interpenetrating layers that constitute a locality. In recent works, he has expanded to explore how paper can become a locus of multiple and overlapping meanings, through which ideas on the natural world, domestic sphere, and urban landscape may be negotiated.

In 2015, his exhibition Isles received the Ateneo Art Award, which allowed him to participate in studio residency grants at La Trobe University Visual Arts Center in Bendigo, Australia; Artesan Gallery in Singapore; and Liverpool Hope University in Liverpool, United Kingdom. The following year, Villamael participated in the Singapore Biennale and, in 2018, in the Biwako Biennale in Japan. Villamael is a recipient of the prestigious Cultural Center of the Philippines Thirteen Artists Award (2021) and was recently invited to the Civitella Ranieri Visual Arts Residency in Italy (2025).

He has exhibited at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris; MAIIAM Contemporary Art Museum in Chiang Mai; Para Site in Hong Kong; Mizuma Gallery in Tokyo; the Arts House in Singapore; ROH Projects in Jakarta; and the Metropolitan Museum in Manila. Upcoming, Villamael will exhibit the seventh iteration of his foundational Locus Amoenus series in Musafiri: Travellers and Guests at Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin (2025).

My work uses the process of paper-cutting as a way to mediate and meditate upon history, collective memory, and the interpenetrating layers that constitute a locality. This process initially started out of necessity instead of desire—at the onset of my art-making practice, it was one of the few mediums I could afford to do. But out of economic considerations, it has grown into a practice of concept as much as cutting—liberating the material to become an arbiter of meaning.

In the medium, I saw an opportunity—to create something with any available material I can manipulate; to have a technique that is deliberate, almost meditative regardless of the scale; to say what I wanted to say and make my ideas tangible with the simplest possible material.

A big part of my practice involves a dissection—both literal and figurative—of the documentation of our history, especially the process of cartography. Through geopolitical delineations and divisions, maps represent the narrative of political power, cultural life, and human longing in a particular point in history. Not only do they function as instruments which represent the accepted and contested geopolitical boundaries, maps also serve as symbols of competing world views or ways upon which reality is first defined by power brokers or hegemons and subsequently apprehended by the masses.

In that sense, maps—or any kind of documented history—are instruments of power as well as human longing. They are both political and personal. They speak of national aspirations as well as of individual ambitions.

In as much as cartographers and historians seek to present geopolitical reality as accurately as they understand it to be, these documentations turn out to be political and navigational instruments that only present partial truths, hiding the invisible realities of the marginalized in the fringes of its demarcated spaces and presenting world views colored by personal experience. In a sense, they conceal as much as they reveal.

I’ve always been fixated on the idea of loss, may it be dealing with the collective narrative or zooming in on my own personal history. It’s a constant mapping of how it is to be a Filipino with a convoluted past and an uncertain present, drawing strongly on the complexity of heritage to make sense of the narratives that obscure identity.

Since the prevalence of colonization to present, much has been erased, purposely hidden and misinterpreted about our history. It is this reshaping and myth-making that led me to investigate the way our identities have been imagined, invented and formed through societal interpretations which influence the way we see ourselves as people, nation and self.

It is the same method that I’ve applied to my own personal history, studying the socioeconomic and geopolitical elements that have created distance between my own family and dissecting narratives of trauma passed down from one generation to the next.

To me, this process is a form of emotional forensics, an investigation of history, loss, and the ways we piece ourselves together by slicing and cutting away the ties that bind, allowing ourselves to create our own narratives by reconciling with our past.

Selected Works

Selected Works

Selected Exhibitions

Selected Press

- T List: See This | In Berlin, an Artist’s Plant Life Made of Maps

- The Must-See Art Shows and Exhibitions of 2025

- Ryan Villamael Portrays Personal and Collective Migration Histories in his Paper Sculptures

- Observer’s Guide to the Must-See Gallery Shows Now On in New York

- Ryan Villamael

- Insights: Ryan Villamael

- Ryan Villamael will always be Los Baños’ artist in residence

- ‘Return, My Gracious Hour’: Reinterrogating Nostalgia of the Past

- Paper’s elusive histories

- Ryan Villamael: His paper universe

- Ryan Villamael’s Cascading Floral Sculptures Reconsider Maps and Identity

- Cultural Center of the Philippines 2021 Thirteen Artists Award

- Conversation with Liv Vinluan and Ryan Villamael

- ‘Possibilities and discoveries’: The 2021 CCP Thirteen Artists awardees

- And the 13 winners are…

- Nontawat Numbenchapol and Ryan Villamael

- Meet Ryan Villamael, The Artist Who Turns Paper Into Fantastical Sculptures

- Ryan Villamael’s Paper City

- CNN Philippines Life | How Ryan Villamael relearned how to paint

- Ryan Villamael’s Paper City

- This Artist Transforms Paper Into Awe-Inspiring Works of Art

- Interview with Ryan Villamael

- Ryan Villamael's paper art allows him to see the world